This is a test

- 334 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Incidence of Income Taxes

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this book, first published in 1939, an analysis is given of the incidence both of partial income taxes, that is of income taxes which are levied on the incomes arising from particular lines of industry, and of a general income tax.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Incidence of Income Taxes by Duncan Black in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

I

THE OLDER THEORY OF THE INCIDENCE OF A GENERAL INCOME TAX

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY

FOR, a considerable period it has been held by economists that the incidence of a general income tax is not shifted, and that such a tax has no tendency to raise or otherwise alter the prices of commodities. The most careful formulation of this theory, which, for convenience, I refer to as the older theory, can be found in the writings of Professor Seligman1 and Mr. Coates;2 and a view in some respects similar, was adopted by the Colwyn Committee on National Debt and Taxation which drew up its Report in 1927.

In December of 1927, however, a very important article by Mr. D. H. Robertson appeared,3 which made it plain that the arguments on which the economists had relied to show that the incidence of a general income tax is not shifted, were erroneous. The whole matter was seen to require further investigation.

The following chapters of Part I of this book outline the older theory of the incidence of a general income tax and go on to criticise this theory. When it has been made clear that the older theory is no longer tenable, instead of proceeding direct to a reconstruction of this theory we deal in Part II with the incidence of partial income taxes, i.e. taxes assessed on the earnings of particular lines of industry. These taxes are interesting and important in themselves; and an insight into their nature helps one to an understanding of the incidence of a general income tax.

In Part III the problem of the incidence of a general income tax is again taken up; to construct a theory of the incidence of a general income tax is the main object of this book. Part IV goes on to supplement Part III and deals with some related questions.

Any of the Parts I, II, III or IV can be read independently of the others. If the student’s interest is mainly in the incidence of a general income tax, he may omit reading Part I or Part II; or better, he might read Chapter II and then pass on to Part III. Or, if he wishes to examine the incidence of partial income taxes, he can read Part II alone.

1 E. R. A. Seligman, “Income Taxes and the Price Level”, in his Studies in Public Finance, p. 59, and republished as Appendix XII, Appendices to the Report of the (Colwyn) Committee on National Debt and Taxation.

2 W. H. Coates, “Memorandum on the Incidence of the Income Tax”, Appendix XI in the same volume of appendices.

3 D. H. Robertson, “The Colwyn Committee, the Income Tax and the Price Level”, Economic Journal, 1927.

CHAPTER II

THE THREE ARGUMENTS OF THE OLDER THEORY OF THE INCIDENCE OF A GENERAL INCOME TAX 1

1. DOWN to 1927 it was generally held by economists that the incidence of a tax on income is not shifted but remains where it has been placed. Such a tax, they believed, leaves the prices of commodities and the rewards of the factors of production, at the same levels as it had found them. The only difference introduced into the situation by the tax, according to this theory, is that each person hands over a portion of his income to the Government for its uses, instead of using it on his own account.

The theory that the economists had put forward can be summarised as follows, in a way which shows the relationship between its different parts. There are three arguments in the theory:

(i) An income tax which has been imposed, leaves each producer still a producer in the industry in which he had been to begin with.

(ii) The number of firms in each industry remains constant.

(iii) Each firm places the same quantity of goods on the market as it had done to begin with.

Hence, the theory concludes, the total supply of each commodity is unchanged by the tax. Therefore the price of each commodity is unchanged.

Let us state each of the arguments of this theory in turn; afterwards we go on to examine and criticise them.

(i) The first argument, as the economists who use it are careful to point out, only applies to the case of a general income tax, which is imposed on all branches of industry. When a general tax of this kind is imposed, it will not pay any industrialist to transfer his business from one branch of industry to another; because he could not escape the tax by doing so. Let us suppose that the entrepreneur’s income in his present branch is R; and that after payment of the income tax he is left with 80 per cent of R. Then 80 per cent of R will still be a greater net income than it is open to him to obtain in any other branch. He will, therefore, remain in the same branch as he had been initially. Thus the tax sets up no tendency to a transfer of resources between the different portions of the industrial field, but leaves each producer still a producer in that industry in which it had found him to begin with.

(ii) The Marginal Firm or No-Profits Firm argument is stated by Seligman as follows: “… the question [is] how the marginal producer, the producer at the margin, is affected…. A tax on income is a tax on net profits; and net profits are not cost, but the surplus over cost. A tax on profits cannot reach the man who makes no profits. But the man at the margin who makes no profits … pays no tax because he makes no profits…. If the man at the margin who at any particular time fixes the price for the entire supply of commodities that is sold in the market pays no tax, how can the income tax be added to the price? The tax on profits is paid only by the man who makes profits, that is by the intra-marginal producer, not by the marginal producer. But the tax paid by the intramarginal producer cannot affect the price which is fixed by the marginal producer who pays no tax.” 1

The skeleton of this argument would be:

Price is determined by the marginal or no-profits firm.

This firm makes no profits and therefore pays no income tax. Since it pays no income tax, its position is unaffected by the tax. Price, therefore, is unaffected by the tax.

That is, although a general income tax be imposed, it will leave the price structure unaffected.

(iii) The Marginal Unit argument of this theory completes the proof. In addition to there being a marginal or price-determining firm, these theorists hold, there is for each firm a marginal or price-determining unit of production. The marginal unit for any firm is the last unit of production that the firm is just induced and no more to place on the market. Sir Walter Layton states the argument briefly and effectively thus: if we consider any firm, “production under competition continues up to that point where the last unit of output makes no contribution towards profit and therefore nothing towards the revenue of the State. This is the unit of production which determines prices, which should therefore be unaffected by a tax on those units which yield some profit. On the same reasoning, the amount of output should remain unchanged.” 1

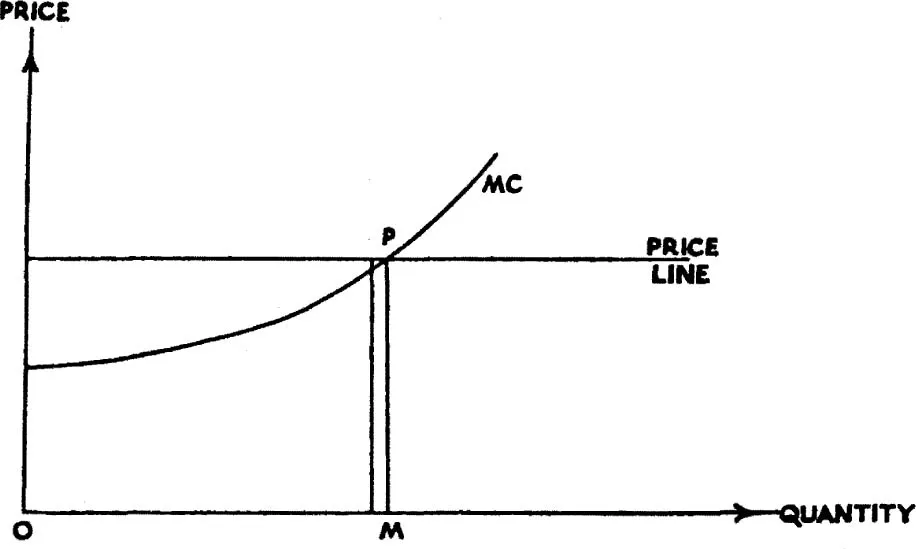

The argument can be illustrated very simply by the curve of marginal costs MC in the diagram. If the firm is producing in a competitive market, the price of the commodity remains unchanged whether the firm increases or reduces its output: price therefore can be shown by a horizontal straight line.

DIAGRAM I

The producer, it is known from economic theory, will in these circumstances continue production just up to the point at which marginal cost is equal to price, and no further. If he were to produce beyond M he would incur a loss on the extra units that he produced: if he were to produce less than OM units he would forgo a gain on the units he had refrained from producing. The OMth unit which he produces, fetches a return shown by the area of the very thin rectangle in the diagram: and the cost of production of this unit is given by the same area. This unit just covers its cost of production and no more. It yields the producer no profit over and above its cost of production. The producer makes no payment of income tax on account of this unit, since he makes no profit from it. Hence the production of this unit is left unaffected by the income tax; the OMth unit will continue to be produced after the tax as it had been before it. But if the OMth unit is produced, the firm’s output must be unchanged, because the firm had initially produced OM units of output.

Thus the economic theory which we outline, seeks to establish that when a general income tax is imposed, there will be no interchange of resources between the different branches of industry, that the number of firms in each branch will remain unchanged, and that the output of each one of these firms will likewise be unchanged. If the logic of these arguments be correct, then the theory holds itself to have established that commodity and factorial prices will be left unaltered by the tax. But are the arguments of the theory valid? That is what we must discuss.

2. (i) The first argument of the theory we are describing affirms that since the whole of the economic field is taxed, each manufacturer will continue in the same line of production as before. An assumption underlying this argument is that the gross income of each person in the new situation, i.e. his income before he pays the income tax, remains the same as it had been initially. Let us, to begin with, grant this assumption.

Even then the conclusion which the argument purports to arrive at will not follow. There will still be some transference of resources from one part of the field to another. One requirement which must be fulfilled in order that a condition of equilibrium should exist, is that the “net advantages” offered to a person by his occupation, should be the highest on his scale of preferences which it is open to him to attain, when not only the monetary reward of the occupation but also the social esteem, leisure, etc., attaching to it are counted among its net advantages. The income tax reduces only one form of the net advantages of different occupations, the monetary advantage. Consequently, a person who was formerly hovering in choice between two occupations, one whose net advantages are largely monetary and another whose advantages are largely nonmonetary, and so not taxed, may now tend to favour more strongly the class of occupation affording its net advantages more largely in the non-monetary form. Or even, as can be shown,1 it is possible that the individual will, in these circumstances, be brought by the income tax, from a state of indifference in choice, to a decision favouring the occupation which will afford him the larger monetary income. Again, a person of certain psychological tastes may be led to retire earlier from business as a result of an income tax which swallows up part of his earnings: the effort may then seem to him not worth while. Yet the same tax may induce another man to extend his business life over a longer period, until...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PART I: THE OLDER THEORY OF THE INCIDENCE OF A GENERAL INCOME TAX

- PART II: THE INCIDENCE OF PARTIAL INCOME TAXES

- PART III: THE INCIDENCE OF A GENERAL INCOME TAX

- PART IV: ADDITIONAL PROBLEMS

- APPENDIX

- INDEX OF NAMES