1 Introduction

Environmental health as a profession has a long history of taking action to protect the public from illness and accident in the home, workplace and elsewhere. Environmental health is a specialism of public health, and practitioners are often employed in local authority regulatory roles, although an increasing number work in the private sector. The regulatory role sets it apart from other public health occupations, as practitioners can serve legal notices and take prosecution action to enforce change where necessary. The focus of this book is on environmental health in this local authority context.

Environmental health activities are geared towards the prevention of harm and providing the conditions for citizens to live healthy and long lives. These actions tend to be structural, dealing with the causes of issues, and are thus known as ‘upstream’ interventions, in comparison to ‘downstream’ interventions, which are based on alleviating the effects of adverse impacts rather than preventing them occurring.

The outcomes of upstream interventions and actions can be difficult to measure and sometimes will only be felt in the long term, in some cases taking many years to secure health improvements. Such actions, particularly if regulatory, may cause inconvenience and expense with no immediately visible result and so can be unpopular with individuals, communities and even with government. Thus, a career in environmental health can be challenging as well as rewarding!

Health inequalities are one of the most pressing public health issues we face globally and are particularly acute in countries with neoliberal economies and large societal inequalities, such as the UK and the US (Wilkinson and Pickett 2010; Schrecker and Bambra 2015). The term describes differences in health (both morbidity and mortality) between people in different socio-economic groups, with longer lives and better health experienced by people in higher socio-economic positions (Marmot and Wilkinson 2006; Marmot 2010).

In ‘The Health Divide’, Margaret Whitehead offers a useful definition, including the concept of fairness in relation to tackling inequalities:

In health terms, ideally everyone should have a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential and, more pragmatically, none should be disadvantaged from achieving this potential if it can be avoided.

(Whitehead 1988: 222)

And the link to social justice, equity and the resultant moral imperative for action has remained important for many working in this area, including myself.

The differences in morbidity and mortality apply at all levels in society, and we now know that having large gaps between the socio-economic status of different groups in society is detrimental not only to the people at the bottom but also to those at the top. This is thought to be related to the stress associated with either maintaining a level of status and material wealth or in feeling of diminished value if this is not achievable (Wilkinson and Pickett 2018).

Although the UK has measured, monitored and researched health inequalities for longer than any other country (Mackenbach 2010), they have remained stubbornly persistent despite various policy initiatives (Bartley 2017). This failure has been acknowledged by the central government:

Health inequalities between rich and poor have been getting progressively worse. We still live in a country where the wealthy can expect to live longer than the poor.

(Department of Health 2010)

However, there appears to be a reluctance at a high level to acknowledge and act upon the established links between health inequalities and other societal inequalities, including economic and power disparities, and how these intersect between different population groups.

Health and societal inequalities are complex and intractable and are also known as ‘wicked’ issues (Hunter, Marks et al. 2010), as the causes are multiple and far from straightforward to address and in some cases not fully understood. Nevertheless, even in the face of little or no progress, there is an ethical imperative to take action, since health inequalities represent a great deal of avoidable suffering (Marmot 2010). To illustrate, there is a 28-year gap in life expectancy between wealthy and deprived areas in one Scottish city (Marmot 2015).

An important but often unrecognised aspect of the environmental health role is the effect of upstream interventions tackling the ‘causes of the causes’ of health inequalities, also known as the ‘social determinants’ of health. Environmental health practitioners hold a key position in being able to take effective, enforceable action to tackle some of the causes of health inequalities at a local level and, with coordinated effort, to impact morbidity and mortality at a national population level, too.

Interventions such as improving privately rented housing stock, dealing with air, water and land pollution, protecting people from illness and injury at work and ensuring safe food and water all make a significant contribution to protecting the public’s health. Nevertheless, the potential of the work to tackle health inequalities is often overlooked by people both within and outside the profession.

Chris Day sums up the imperative for environmental health practitioners to protect the most vulnerable members of society who are not in a position to improve their own circumstances:

we should recognise where the gaps exist … and then do something ourselves to fill it … [because] as a group of front-line professionals we encounter in our daily round most, if not all, of the stressors that impact on human health, and driven by a desire to better the lot of those dealt a poor hand from the start, challenge the environmental service to deliver to the needs of those who may not have the capacity to speak up for themselves.

(Day 2011: 64)

This statement alludes to societal inequalities impacting those affected by being in lower socio-economic positions across the course of their lives; these are deeply connected to inequalities in health. Whilst tackling the causes of health inequalities crosses the remit of many professional groups and cannot be addressed by one group alone (and certainly not only the healthcare services), environmental health has a significant potential to alleviate suffering and to address the immediate causes, and the causes of the causes, of ill health and accidents.

As an environmental health practitioner, there have been many situations where I have taken action to protect people who are unable to resolve matters themselves, for example, in improving workplace conditions, ensuring good food hygiene, dealing with noise and odour pollution and addressing unsafe housing. Over many years, I noted the quiet but important work of practitioners, hidden behind the scenes, was often unrecognised and siloed, taking place in isolation from other public health practitioners with similar goals and aspirations. Thus, when I began my PhD looking at local policies aimed at tackling health inequalities, it was important to me to include a focus on my own profession, and I am grateful to my supervisory team for supporting this decision and to my fellow practitioners for their openness, making the research possible.

My research looked at newly established English local governmentbased public health policymaking structures called Health and Wellbeing Boards, focusing on four case study sites in the Midlands and North. In addition, I spoke to environmental health practitioners and managers at 15 additional sites across the country, interviewing 50 people in total. I also looked at the documents produced by the boards and observed meetings over a 12-month period. Case study site descriptions are given in Table 1.1, and additional site descriptions are given in Table 1.2.

Table 1.1 Case study site numbers and descriptions

Case study site | Description | Unitary/Upper-tier council |

1 | Midlands, suburban and rural areas, affluent with North-South split in areas of deprivation. The population is both growing (rising birth rate) and ageing, and 90% describe themselves as ‘white British’. There are concerns around dementia, hospice provision and carers. Unemployment levels are falling, although youth unemployment remains an issue. | Upper-tier |

2 | Midlands, suburban and rural areas surrounding a major multicultural city, primarily affluent but with pockets of deprivation. There is a growing and ageing population, and the number of people below pension age is lower than the UK average. Ninety per cent describe themselves as ‘white British’. | Upper-tier |

3 | Midlands, urban, with significant areas of deprivation and a ‘young’ population (almost half are under 30) which is very ethnically diverse, with 90% of people in some wards describing themselves as other than ‘white British’. Suburbs are generally affluent, and inner-city population density is high. Air quality is often poor, and there are concerns about obesity, particularly in children. | Unitary |

4 | North West, urban and suburban with significant areas of deprivation. The population is ageing and almost 97% describe themselves as ‘white British’. Life expectancy is lower than the national average. Smoking, drinking and substance misuse are concerns. | Unitary |

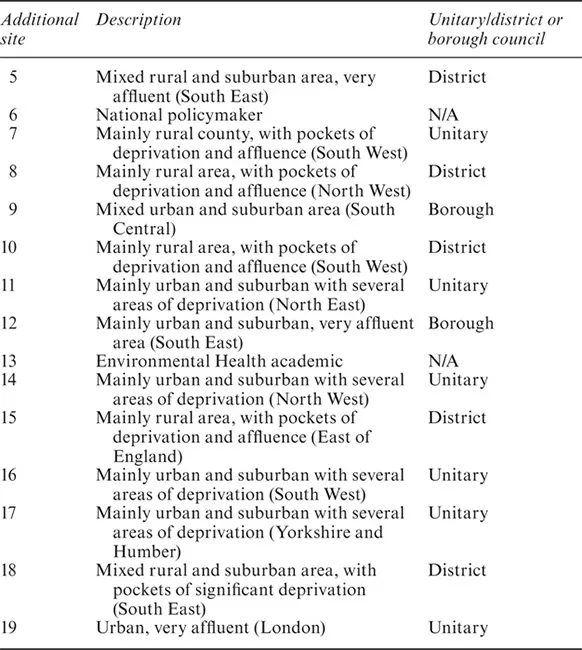

Table 1.2 Additional site numbers and descriptions

At the additional sites, I focused on environmental health services, and a range of unitary, district and borough councils were selected for inclusion across a wide geographical area. The Table 1.2 shows the site numbers, provides a short description of the area and the structure.

Health and Wellbeing Boards became operational in 2013 and are (amongst other things) charged with tackling health inequalities in their local areas and designed to bring together high-level policymakers across local authorities and health services. They are required to carry out a Joint Strategic Needs Assessment of local health needs and to develop Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategies to address those needs. The idea is that the agreed policies are then followed by commissioners of services in a coherent and joined-up way with the aim of improving the health of the local population. A list of statutory members was provided by central government, with a focus on elected members, directors of public health, representatives of adults’ and children’s services and healthcare services, but did not include environmental health representatives, and I was interested in how my profession would fare in these arrangements.

Whilst the focus of the research was on one type of policymaking arrangement, it has generated helpful insights into how the health inequalities are being understood and tackled and how environmental health fits into the narrative at a strategic level. For this reason, and a...