WHO ARE LEARNING-DISABLED CHILDREN?

Terry is a well-built robust child of eight years. The middle child of a family of three, his main problem is in reading. This seems all the more pronounced as his younger sister, aged six years, is a fluent reader. On the surface, he is a happy-go-lucky child, liking to play outside, climbing and playing football. However, this physical activity may mask a number of problems. He is poorly co-ordinated, and other children do not like playing with him. At school his class teacher describes him as a ‘jittery youngster’ who finds it difficult to sit still. He has had speech therapy from the age of four and still has difficulty in pronouncing words, though he told the story of ‘Glack and the Beanstalk’ with great vigour.

Terry’s academic progress is very slow. He has a reading age of five years and eleven months on the Schonell test, and he writes poorly. His ability in arithmetic is a little better and he seems to be keeping up with the rest of the class. When tested with the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children he obtained a Verbal IQ of 121 and a Performance IQ of 86. Visual-motor abilities seemed to be poor as his drawings from copy on the Bender-Gestalt test were inaccurate.

This is only a brief description of a child with learning difficulties. It is fairly superficial in its description of the child’s character and mentions a few significant test results. However, although this description is incomplete, it serves to illustrate the individuality and complexity of each learning disabled child.

We can say that we have some information about what the child appears to be like, from observation, from reports of the school teacher and from his or her parents. This information may give us some insight into the personal misery the child is likely to be experiencing. In this case, Terry’s high achieving younger sister, his need for activity both inside and outside school, and so on. It also gives some insight into personal strengths. Here the child’s love of stories was apparent despite his speech problems.

Test information can also give some indication of strengths and weaknesses, and may serve as a pointer towards further information gathering. In the case of Terry, it seems that all his strengths are verbal ones (despite his speech difficulty) and his weaknesses are in the perceptual motor area. So we can set up a working hypothesis which gives us an indication of which areas to search next. In the case of Terry we might want to see whether he attempts to use his strength when learning to read or in other tasks. We might expect him to use linguistic cues in reading and that perceptual-motor difficulties would be obvious here also. The importance of setting up such working hypotheses cannot be overemphasised.

Each learning-disabled child (indeed every child) is a person with individual strengths and weaknesses. It is only through the exploration of the strengths and weaknesses that a proper remedial program can be devised, one which helps the child to learn through his strengths, whilst building up or compensating for his weaknesses. This book attempts to delineate the various strengths and weaknesses experienced by learning disabled children and some specific methods of remediation. The desirability of such diagnostic formulation and remediation has been apparent since the 1981 Education Act, which followed on the Warnock Report of 1978 and was an important milestone in our understanding and treatment of learning disabled children.

The Warnock Report and its Aftermath

The Warnock Report (1978) was revolutionary in its recommendation that the categorisation of handicapped children be abolished. Such categorisation had been prevalent for many years and was a feature of the 1944 Education Act. In all, eleven categories of children were in common usage, ranging from maladjustment to the partially deaf and educationally subnormal. This categorisation was in part responsible for the segregation of handicapped children into special schools. Warnock recommended that the term ‘children with special needs’ replace the existing categorisation. This was in order to emphasise the needs of children rather than their handicap. Thus Warnock was providing a more appropriate educational rather than a medical perspective.

The Warnock Report also recommended that the term ‘children with learning disabilities’ should be used as a term to cover those children who are categorised as ESN and those with educational difficulties who are presently covered by the remedial services. Such learning disability could be deemed severe, moderate or mild. Children of average or above average intelligence who had a learning problem might be called ‘children with a specific learning disability’ if so desired.

The reasoning behind the abolition of categorisation was partly the desire to treat all children as individuals with individual needs, but also because categorisation was seen as logistically impossible since most learning-disabled children have more than one learning disability. Therefore many children would present problems because they would fall into two or more categories simultaneously. A severely mentally-handicapped child, for example, usually has an additional physical handicap and may be blind or deaf. At the other end of the scale a child who has problems with reading may have additional speech and auditory discrimination problems. A clumsy child or a hyperactive child would be likely to have perceptual problems and difficulty with the three Rs.

In the 1944 Education Act it was deemed necessary to educate each child according to ‘age, ability and aptitude’. The 1981 Act revised this by adding the words ‘... and to any special educational needs he may have’. A child was said to have special educational needs if ‘he has a learning difficulty which calls for special educational provision to be made for him’. Learning difficulties are of three kinds, as outlined in this act. Firstly, where the child has greater difficulties in learning ‘than the majority of children of his age’. Secondly, where he has a disability or handicap ‘which prevents or hinders him from making use of the educational provision’. Finally, there are the children under five years of age who would fall into the previous two categories whenever they do reach the appropriate age.

This Education Act has been criticised as presenting a circular definition (Wedell, Welton and Vorhaus, 1982) and as being rather less precise than the Warnock recommendations (Brennan, 1982). The Warnock Report specifies that the provision be in terms of equipment and resources including new buildings, the provision of a special education curriculum and ‘the social and emotional climate in which education takes place’. The provision of the special education curriculum might seem an especially tall order and this is one reason why the Warnock Report emphasises teacher training. Certainly the employment of teachers and other professionals with appropriate background and training would be necessary to implement such a recommendation.

The 1981 Education Act has also had important sequelae (see Newell, 1983). One important feature of it was that each child in need of special education had to have a statement made of his or her educational needs. In addition to describing the child’s specific needs, this statement has sections which attempt to outline how these needs shall be met in terms of school arrangements and educational provision. There are important appendices which give information from parents, teachers and several professional advisers. All those who are called on to give such information are advised that their information be given in three categories which are:

- 1. Description of the child’s functioning

- a) Description of the child’s strengths and weaknesses.

- b) Factors in the child’s environment.

- c) Relevant aspects of the child’s history.

- 2. Aims of provision

- a) General areas for development.

- b) Specific areas of weakness or gaps in skills acquisition which impede the child’s progress.

- c) Suggested methods and approaches.

- 3. Facilities and resources

Thus the information needed for each child is quite precise. Any professionals who are involved with children in need of special education will have to have a clear idea of the learning difficulties experienced by the child and how these might be remedied.

There are other important developments in Special Education which have arisen because of the Warnock Report and the 1981 Act. Not the least of these is the policy of integration of children with special needs into ordinary schools (see Hegarty, Pocklington and Lucas, 1981).

The Incidence of Learning Disability

The estimate of children in need of special education lies somewhere between 15 and 20%. This former figure is in agreement with the 1944 Education Act (14 to 17%). Pringle et al, (1966) gave a figure of between 13% and 15% of seven-year-olds. The 13% is the figure given by headteachers as an estimate of the number of children who could, with some advantage, have been given special educational help in ordinary schools. In a follow-up study of all the children in the study at age sixteen years, 13% were receiving help in ordinary schools, 1.9% were in special schools and 3% were estimated as being in need of special education. Special help within schools was deemed necessary for a further 5.5% (Fogelman, 1976). Hence, this is a total of 23.4% in need of special education. Rutter, Tizard and Whitmore’s (1970) Isle of Wight survey judged that for four types of handicap (intellectual, educational, psychiatric disorder and physical handicap) 16.1% of children in the nine to eleven age group had a chronic or recurrent handicap. This figure of one in six children is seen as an underestimate in view of the fact that not all handicaps were covered. Most of these figures would be in support of the statement given by the Warnock Report that ‘one in six children at any one time and one in five children at some time in their school career will be in need of special education’.

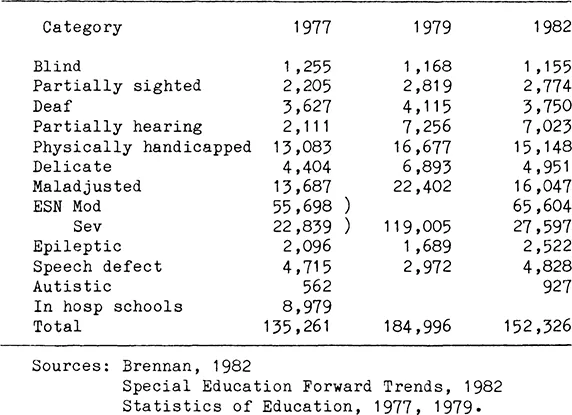

A distinction is often made between the total group (the 20%) and the larger fraction (the 18%) who represent the children seen in ordinary schools. The 18% does not usually appear in estimates of children receiving special education (see Table 1.1) given as a total of 152,326 children. This represents 1.49% of the total school population of England (Special Education Forward Trends, 1982). 1.41% of children were in special schools and is the number of children who had been ascertained as in need of special education. It is with this 18% that this book is directly concerned. It represents the five or six children with special educational needs in every class of thirty children.

Table 1.1: Numbers of Children Receiving Special Education by Category, in England and Wales

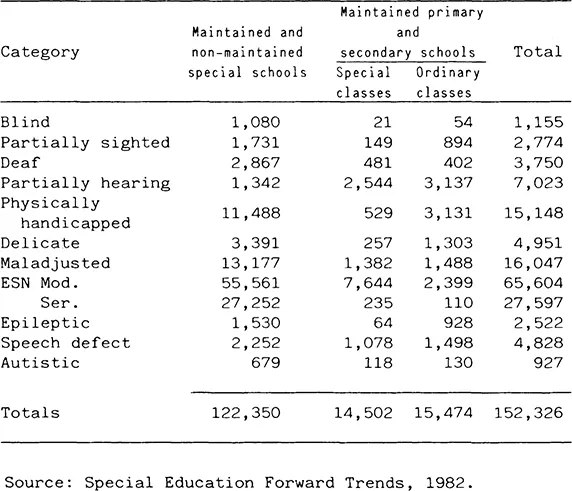

Nevertheless, there are some important pieces of information to be gleaned from the statistics in special education (see Table 1.1). The 1982 figures show some important trends when compared with previous years (see also Brennan, 1982). Firstly, there is some fluctuation in the numbers of children in certain categories, that is, in the deaf and partially hearing, children with speech defects and delicate children. Secondly, there seems to be a slight increase in the numbers of maladjusted and autistic children. There is also an increase in the numbers of children in ordinary schools over time. The majority of partially hearing and over a fifth of the children ascertained as being ESN (M), delicate, epileptic, speech defective and physically handicapped are now educated in ordinary schools (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.2: Distribution of Children Receiving Special Education in England and Wales in 1982

Hence we can expect that many children with ascertained handicaps will be in ordinary schools in addition to the 18% without obvious handicap who are still in need of special education.

A further point which Rutter et al (1970) emphasised is that many of these children will have more than one learning disability. Of the quite severely handicapped children he surveyed, one quarter of the children had more than one handicap. For example, of the educationally handicapped (children with attainments well below average) 43% had additional handicaps. This category would be those children usually labelled remedial who are found in ordinary schools. It would seem likely then that two or three of the five or six children in the class of thirty who have special educational needs would have more than one learning difficulty.

LEARNING-DISABLED CHILDREN IN THE NORMAL CLASSROOM

Apart from the physically handicapped or partially hearing child whose handicap is obvious and who gains sympathetic attention, there is a small group of learning-disabled children in every class. They are often euphemistically referred to as slow learners or remedial, and sometimes less kindly by children as dumbos, thickies or worse. Unfortunately these attitudes may be unwittingly perpetuated by the teacher, who is constantly frustrated by the lack of progress in this group despite frequent attention. The children may go to the remedial teacher for half an hour a day, but this is a drop in the ocean of time that the class teacher has to teach them. It is hardly surprising then that the class teacher comes out with such remarks to the visiting psychologist as ‘Oh, you can see those children any time you like, I can’t do anything with them.’

The Warnock Report directly addresses the needs of children in so-called remedial groups, who ‘have a wide variety of individual needs, sometimes linked to psychological or physical factors, which call for skilled and discriminating attention by staff in assessment, the devising of suitable programs and the organisation of group or individual teaching whether in ordinary or special classes’. Here we are given some idea of the complexity of the problem of educating children with learning difficulties in the ordinary school. The children have widely differing needs, some in terms of physical or other handicap, some with emotional problems and most with learning difficulties in more than one area. In order that these children can attain according to their ability, they need highly skilled and personal teaching. There is a great need for children’s learning difficulties to be individually assessed and provided for in terms of individual programs. This is a mammoth task for the ordinary school teacher, but not an insurmountable one, as I hope to demonstrate in this book.

The Prepared Classroom

How do we cater for such children in the normal school day in the normal school environment? There are two main approaches to this problem, that is by remedial withdrawal group and by special class. The remedial withdrawal group is a group which is taken out of the ordinary classroom from time to time to be given remedial teaching, and seems to be the most popular arrangement at this time, especially if the remedial teacher works in the normal classroom from time to time. It is seen as the better alternative, largely because the children are mainly integrated into the normal classroom, and also a large number of children can be catered for in the school day. In the special class children will get more suitable work and attention to their specific needs, but they may be seen as different from other children, which it is argued is a stigma that should be avoided if at all possible. Of course children who are part of a withdrawal group may also be stigmatised in this way.

How can the classroom or remedial teacher organise her classroom to the benefit of the children with learning difficulties and the ordinary children? Whether the classroom is a special class or an ordinary class, one approach is to think of the classroom as a prepared environment, in the sense used by Maria Montessori (1945), as a learning environment which caters for the individual needs of all children. In such an environment children can work at their own level, with the aid of the teacher. The setting up of such an environment has been widely adopted in the infant school following the recommendations of the Plowden Report (1967). There is no reason why such ideas should not be adopted in the junior and even secondary school and is indeed recommended by some. Such an environment needs a great deal of preparation on the part of the teacher, but, if properly executed, individual pupils will benefit. I have seen such methods adopted both by an ordinary p...