1 The Legacy of the Garden City Movement

At the end of the First World War the government promised to build half a million houses of a kind completely different from that to which the majority of the population was accustomed. In making this pledge the government took its model from the garden city movement which, in the years before 1914, had developed a format for residential development and. design that was strikingly unlike that found in existing towns. This chapter looks at this transformation in house and environment provided by the garden city movement, and deals both with the considerations that lay behind it and with the innovations in residential design that followed. In relation to the latter it focuses in particular on the writings and designs of Raymond Unwin, for Unwin was not only the leading architect of the garden city movement before the war (involved with Letchworth Garden City, Hampstead Garden Suburb and numerous other schemes) but after 1914 became the central figure in the design of state housing.

The Garden City Movement

The garden city movement was not, as the term might seem to imply, a homogeneous group with a single ideology, but was rather a heterogeneous collection of different groups and interests, linked only by a common commitment to bringing about a transformation in what was referred to as ‘the housing and surroundings of the people’. At least three distinct strands can be detected within the movement. In chronological sequence, these were: the model villages built by the industrialists Lever and Cadbury; the garden city itself, expounded in theory by Ebenezer Howard in 1898 and founded at Letchworth in 1903; and the garden suburbs, the most famous being Hampstead Garden Suburb, started in 1906.

Since the early days of the Industrial Revolution, factory owners had known that their power over their workforce could be greatly increased if they controlled, not just the jobs, but also the houses of their employees. For instance, in building his factory-village at Copley, outside Halifax, Colonel Akroyd’s motive was primarily to make his mills ‘secure against the sudden withdrawal of workpeople’.1 Towards the end of the nineteenth century a small group of industrialists developed a rather different approach that was to lead them to build model villages of a more ambitious nature. The underlying idea was that, by making a dramatic improvement in the housing conditions of his employees, the employer could make them more contented and therefore more productive. In 1887 Lever Brothers moved their soap factory from Warrington to an open site on the Mersey and, in the following year, started construction of a factory-village of a most spectacular kind. This, they insisted, was not out of philanthropic motives but purely from self-interest: the annual outlay on the village made from the profits of the firm was outweighed by the high productivity and good industrial relations it created. Some years later, in 1895, the Cadbury brothers decided to establish a similar model village adjacent to their cocoa factory at Bournville, near Birmingham. As a Quaker family, the Cadbury’s were a good deal more explicitly humanitarian than the Levers, but their venture in village building was informed by a comparable business sense. As Edward Cadbury stated in 1914, ‘we have always believed that business efficiency and the welfare of employees are but different sides of the same problem’.2 It was this belief that, applied to housing and the physical environment, provided at Port Sunlight and Bournville the beginning of the garden city movement.

The relationship between housing and production was most conspicuous in the factory-villages but it was also implicit in the other two strands of the garden city movement, the garden city and the garden suburbs. Both in Howard’s writings and in practice at Letchworth, the one element that was taken over unchanged from the orthodox town to the garden city was the factory. The garden suburbs were, by definition, intended to be solely residential; by excluding employment and production, they necessarily left the basic economic activities unchanged. Common to all three strands of the movement was the belief that life could be improved in a significant way by a transformation that left the place of work untouched. It was the political ambiguity of this belief that won for the garden city movement the simultaneous adherence of both socialists and capitalists. For socialists such as Raymond Unwin, the garden city movement was the way to make an unparalleled improvement in the lives of the people; for capitalists such as Lever, it offered a way of making the workforce more contented (and thereby more productive) without affecting the basic relationships of capitalist production. It was this latter aspect that, at the end of the First World War, was to make the doctrines of the garden city movement so attractive to the state: for these doctrines implied that, by improving conditions of housing and the physical environment, it was possible to make the people contented with a status quo that was, in other respects, unchanged.

Figure 2 Typical housing built at the turn of the century: speculative builders’ terraced cottages in Tottenham, London

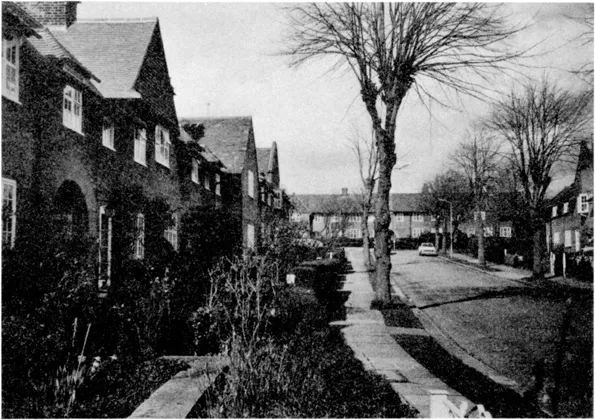

What defined the garden city movement in its own eyes, however, were not political considerations of this sort but the physical changes that resulted: the rejection of the built form of contemporary towns and the search for an alternative based on the village and the countryside (see Figures 2 and 3). At Hampstead Garden Suburb, for instance, it was said that they ‘were getting back something of the old English village life’.3 At Port Sunlight the escape from the contemporary city took a predominantly visual form: ‘a singularly vivid impression of rusticity was created’, it was noted; ‘nothing seems to have been neglected which may produce in the town-dweller the illusion that he has indeed gone back to the land’.4 At Port Sunlight Lever drew on the traditions of the estate village of the country landowner and produced a spectacular re-creation of an old English village, complete with the picturesque trappings of half-timbered elevations, village green and old English inn. When the tenants failed to maintain their front gardens and cottage creepers in conformity with the image desired, responsibility for their maintenance was taken over by the estate office. At Bournville it was the more serious moral aspect of the rural or quasi-rural life that inspired the founder. George Cadbury wrote:

Figure 3 Hampstead Garden Suburb: a cul-de-sac in the early part of the suburb, built by Hampstead Tenants (1908)

I know the Birmingham housing question by visiting men in their houses in the city, and I have had the great privilege of reforming many hundreds of drunkards there. The question that came to me was, ‘What have you to offer the working-man in the evening except the public house?’, and this was the answer I arrived at: ‘The most legitimate occupation is for them to come back to the land’….

I can see no other way of saving England, for if a man works in the factory by day and sits in the public houses by night, what can you expect but a poor emaciated creature without physical or moral strength?5

Accordingly at Bournville each cottage was supplied with a garden of an average size of one-eighth of an acre: ‘nearly every householder spends his leisure in gardening’, it was stated, ‘and there is not a single licensed-house in the village’.6

Bournville also differed from Port Sunlight in the relationship between village and factory. Whereas the buildings at Port Sunlight were directly owned by the firm, the Bournville village was managed by an independent trust and tenancy was not confined to Cadbury employees. Cadbury believed that model houses with substantial gardens would prove profitable in their own right and that – once the initial capital had been provided by a benefactor – the model village could expand on the basis of ploughed-back profits, in the manner of an ordinary business. Accordingly, Cadbury provided the initial capital in the trust deed of 1900 and required that the houses be let at rentals calculated to give a 4 per cent return, so that the accumulated profits could eventually be used to establish further villages. The same idea was written into a similar scheme founded by another cocoa manufacturer, Joseph Rowntree, in 1901. This was the New Earswick village, near York, which in concept was modelled directly on Bournville, although in terms of house design (as will be seen below) it was considerably more innovatory.

The concepts of an economic return and indefinite expansion inherent in the trust deeds of the Cadbury and Rowntree schemes were also implicit in Ebenezer Howard’s idea of the garden city. Here, however, capital growth was to take place on the increase in land values brought about by city development, rather than on the accumulation of profits from house rents. Howard’s proposals had the elegance of simplicity. To start with, a public company paying a limited dividend would be formed and would buy a suitable site consisting of agricultural land, part of which it would develop and let out in plots to companies and individuals for industries and housing. While the agents of the building of the new town would thus be ordinary firms operating in the normal manner, the increase in land value brought about by the development would, thanks to the leasehold system, remain in the hands of the company, to be put to public use. As the first chairman of the Garden City Company said, ‘the automatic rise in the value of the land which will take place as soon as you attract people to your city ... is the real basis of the thing’.7 The increment in value would be enjoyed by the community in the form of public amenities (parks, open spaces, public buildings) and in relief of local rates. At the same time the company would retain control of development, ensuring among other things the preservation of an ‘agricultural belt’ surrounding the entire city. When the garden city reached its population target (Howard suggested 32000), development would continue not by encroaching on the agricultural belt but by establishing ‘another city some little distance beyond its own zone of country’.8 In this way all the advantages of town and country would be combined without the disadvantages of either. More garden cities would be founded as their unique advantages were recognised and existing cities, faced with the exodus of their inhabitants, would be compelled to remould themselves in the new pattern in order to avoid depopulation.

Howard thus envisaged a gradual revolution effected through the agency of the garden city. Capitalism would survive, but shorn of its defects by the social and environmental transformation of what he called ‘Town-Country’. Compared with this grand ideal the progress of the First Garden City founded at Letchworth in 1903 was less than impressive for, despite the interest aroused by Howard’s book, the practical problems of building a new town in the agricultural wastes of Hertfordshire were enormous. It was hard to persuade firms that there was any commercial gain in moving to a site with neither raw materials, energy supplies nor local market. Above all, there was the difficulty of raising capital. By 1914 the town supported a population of 9000 but, according to C. B. Purdom, it was the First World War that brought prosperity and ‘real stability’.9

The garden city took the idea of the transformed environment to its fullest extent by attaching it to an entirely new town; and for this reason, the problems it faced were enormous. In contrast the third strand in the garden city movement applied the environmental improvements of Letchworth or Bournville – low-density housing, quasi-rural surroundings, better housing standards – to the ordinary processes of suburban growth. For this it was not necessary to attract industry; the inhabitants would continue to work in the city but at the end of the day would travel out to the ‘garden suburb’. The first and largest venture of this sort was Hampstead Garden Suburb, founded in 1906 by Henrietta Barnett on a site overlooking the Hampstead Heath Extension, in the preservation of which she herself had played a leading part. Mrs Barnett was interested not just in preserving rural beauty but also in improving society. She aimed both to provide a new home for the slum dwellers from the East End (where, at Toynbee Hall, she and her husband had been working for twenty years) and to reverse what she regarded as the potentially explosive trend towards the geographical separation of classes. Modelled on the English village of the past, Hampstead Garden Suburb was intended to be a socially mixed and harmonious community.

Like the Garden City Company at Letchworth, the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust did not build houses itself, but only developed the site and leased plots for building. There was little difficulty in attracting would-be occupants from the upper end of the market, but house-building for lower income groups was much more problematic, since it was difficult to raise the capital for an enterprise that was never likely to be very profitable. Under the Industrial and Provident Societies Act of 1893, a housing company could register as a public utility society if it undertook to limit its annual dividend to a maximum of 5 per cent. This enabled it to borrow up to one-half (increased in 1909 to two-thirds) of its initial capital from the Public Works Loan Board, but the remainder still had to be found. To meet this difficulty, both the Garden City Company and the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust turned to a new sort of housebuilding agency – the co-partnership society – that sought to raise at least part of its capital from the tenants themselves. The idea of co-partnership housing had been successfully adopted for the first time at Henry Vivian’s scheme at Ealing, started in 1901, and it was to these societies that both Letchworth and Hampstead looked for the e...