![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Bhojpuri in South Africa is (like Tamil and Telugu, and possibly Urdu and Gujarati) a dying language: parents have for some time failed to ensure that it is transmitted to their children, most of whom are now growing up as English monolinguals, with some passive knowledge of Bhojpuri.

Regarding the history and structure of Bhojpuri nothing has been recorded – a statement which holds for all the ’transplanted’ Indian languages of South Africa. Ignorance regarding its place of origin, grammar, evolution in South Africa, and its very name has been Bhojpuri’s fate for most of the twentieth century (for it has always been misnamed Hindi in official notices, and by its latter-day speakers). The following sentiments expressed by Revd. French (1908:150) regarding the development of the language in Natal, are typical of this ignorance:

The Hindustani which many of the Indians here speak is corrupted by Dutch, English, and Kaffir. The original indentured coolies were to a man illiterate, and early began to forget not only the grammatical construction of their tongue, but even the very words, with the result that the present race have a vocabulary of most limited dimensions, with no grammar or idioms.

The missionary’s assumption that it was Hindustani1 (which he had been exposed to in his service in Lahore) that was current in plantation fields of Natal led to his belief that it was a ‘corrupted’ language with no grammar and idioms. This attitude is all too readily expressed by priests, educated people captivated by Standard Hindi, and youngsters understandably eager for any explanation to rationalise their lack of competence in Bhojpuri. It is one of the tasks of this work to establish that it was Bhojpuri that was (and still is) spoken in Natal, and that the grammar of the language in Natal approximates fairly closely to the speech forms of rural north-east India of the nineteenth century. Once this has been done (and it will take two chapters, plus a lengthy appendix), a fair point of departure will have been established for an evaluation of its history in Natal, and of its eventual decline.

Far from being unworthy of serious study (as its detractors believe), South African Bhojpuri presents a partial history of its speakers, who are otherwise silent in the history of colonial Natal. Furthermore, it provides a linguistic and historical link between communities as far off as Trinidad, Guyana, Suriname, Mauritius, Fiji and Natal. Regarding its linguistic orientation, this is a case study in socio-historical linguistics, examining dialects and languages in contact, the nature of ‘transported’ subordinate languages, and the process of language obsolescence.

1.2 THE MIGRATION TO NATAL

Organisation of a system of indentured immigration of indians began in the 1830s, after the abolition of slavery in the British Empire (1834) had brought about a shortage of manual labour in many colonies. The Indian government, entirely British-administered at that time, permitted the recruiting of Indian labourers by the sugar-planting colonies under certain conditions. Five-year contracts between the labourers and the colonial powers had to be drawn up; a Protector of Emigrants had to be appointed in each colony to supervise the terms of indenture; and recruitment of labourers had to be performed by natives of India, under the control of agents appointed by the colonies. Emigration was permitted from three ports only – Calcutta, Bombay and Madras. Colonies more distant than Mauritius had to guarantee a free return passage to workers who had served there for at least ten years (Thompson 1952:11). Under these conditions, thousands of Indians were shipped first to Mauritius (1834), then British Guyana (1838), Jamaica and Trinidad (1844), and later to St Lucia (1856) and Grenada (1858). In 1860 there were shipments to Réunion, Martiniqueand French Guyana (all French colonies), St Croix (a Danish colony), and Natal (a British colony). Immigration to Suriname and Fiji followed in the 1870s.

By the end of the 1850s planters in Natal, growing a variety of crops, faced a shortage of labour. The most obvious source, given the economics of colonisation, the indigenous, mainly Zulu-speaking population, had earlier been consigned to ‘reserves’ not readily accessible to the planters. Furthermore, agricultural work was not the prerogative of males in Zulu economic organisation at the time, and planters did not apparently think of employing the females, who were more accustomed to agricultural toil. Basuto workers and Amatonga labourers from Mozambique were recruited on some farms, but there was still a shortage of labour during peak season (Bhana and Brain 1984:12–13). Many Natal planters looked to India for the supply of cheap – and what they presumed to be – transient labour.

The first ship, Truro, carrying 330 Indian immigrants from Madras and its environs arrived on 16 November 1860 (Meer1980:67). It was followed a few days later by the Belvedere from Calcutta. The departure of these, and subsequent emigrants, was not always voluntary. Revd C.F. Andrews, an associate of Mahatma Gandhi and himself very much involved in the welfare of the early Indians in Natal, said this of the indentured immigration system:

… it was promoted and controlled by Government … Professional recruiters, who were paid a high price for each recruit, were licensed by the Government to go in and out among the village people in order to induce them to leave their homes and be sent abroad for the purpose of labour. This kind of immigration was all too frequently accompanied by deception on a large scale … It cannot be stated too clearly that such immigration is artificial in the extreme. It must never be mistaken for the natural flow of the Indian People to foreign lands. Had it not been for the eagerness of the British Colonies to obtain cheap labour for their plantations, it would never have taken place at all. Indians would have stayed at home. It was Natal, Mauritius, Fiji, etc which wanted the government of India to send Indian labour, and not vice-versa.(Sannyasi and Chaturvedi 1931:28)

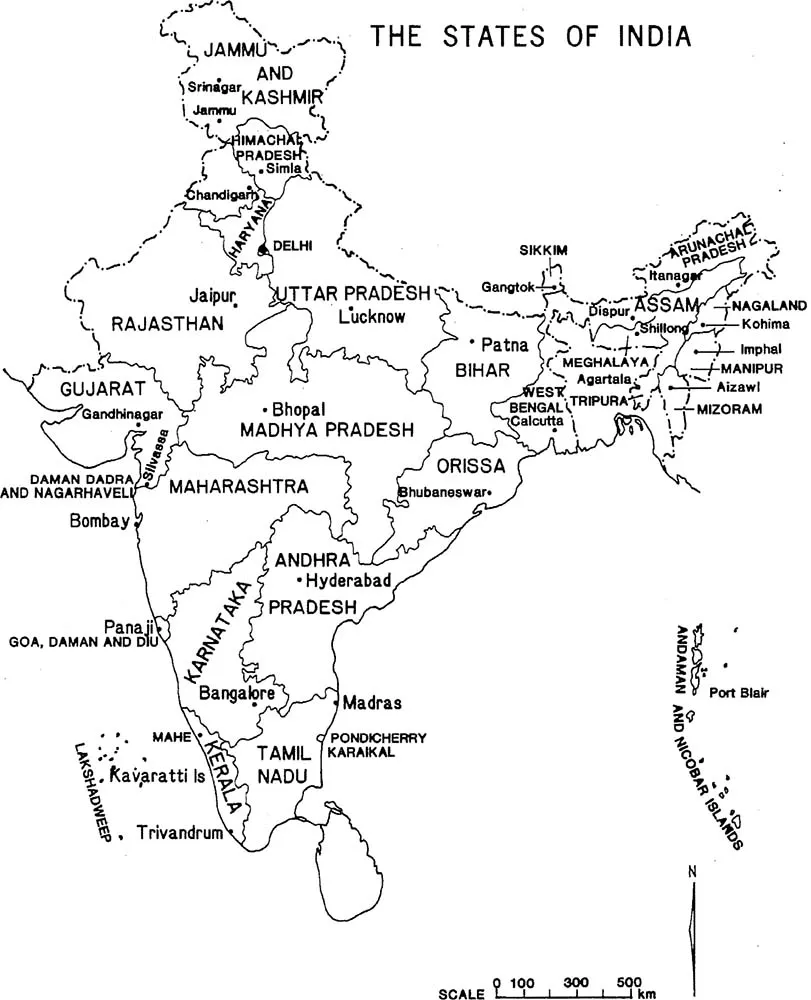

Source: KACHRU. 1983

Map 1— Present-day India

At the same time, it must be conceded that for many of the migrants employment in Natal held some flickering hope of escape from debt, failing crops, unemployment, problems with the law or within the family (so-called ‘push factors’).

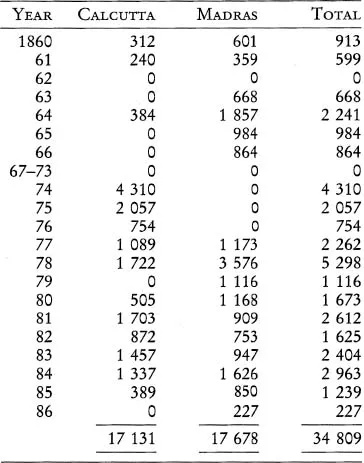

The period of migration to Natal stretched from 1860to1911, with a temporary halt between 1866 and 1874. During this period 152 184 indentured workers had made the journey to a new life, the peak period of migration being between 1874 and 1885 (Meer1980:311–2). Table 1 indicates the number of indentured workers arriving in Natal from Calcutta and Madras from 1860 to 1886.

TABLE 1

NUMBER OF INDENTURED INDIAN WORKERS ENTERING SOUTH AFRICA, 1860–1886

Source: Meer 1980:311–312.

The 1911 Census reports 149 791 Indians resident in South Africa in that year — 93 886 of whom were male; 63 776 of the total Indian population had been born on South African soil.

The bonded labourers soon found out that the new land was not the worker’s paradise that many recruiters had made it out to be. Conditions of work in the early years were most unsatisfactory, as the high suicide rate bears out. Long working hours, inequitable male-female recruitment patterns, flogging, overcrowding in barracks, and poor pay have led more than one historian to remark that the main difference between the conditions of slavery and indentureship was that the latter was not for life (see, for example, Swan 1985:25–26; Palmer 1957:44).

Intitially this class of indentured labourers occupied the lowest rungs of Natal’s socio-economic ladder – the word coolie denoting, at once, ‘Indian’ and ‘indentured worker’. After the initial period of indenture was over (five years, later extended to ten), labourers were theoretically free to seek employment elsewhere, to re-indenture, to return to India (which many did), 2 or to take up farming on small plots of land allotted to those who had served for ten years. This last offer was withdrawn by 1891 (Kuper 1960:2). Imposition of taxes on ‘free’ Indians forced many to re-indenture. Unlike many other British colonies, Natal did offer opportunities for independent economic advancement: immigrants found small-scale vegetable and fruit production more profitable than labouring in the cane fields. As early as 1866 many Indians were being employed on the railways in various menial positions. By the end of the nineteenth century there were 1317 Indian workers in the coal mines of Northern Natal, and thousands employed in jobs that were more rewarding than that of field-labourer – as waiters, hawkers, fishermen, domestics and so on (Bhana and Brain 1984:28).

Another group of Indian migrants came mainly via Bombay to Natal, from 187’ onwards. The group comprised Hindu and Muslim merchants, who arrived voluntarily with the intention of setting up small businesses in various parts of the province. These were the so-called ‘passenger Indians’, whose relative wealth and trading interests kept them apart socially, and sometimes politically, from the indentured Indian.

The earliest of these passenger Indians came from Mauritius, rather than directly from India (Palmer1957:42–3). Links between Mauritius and Natal began in1849 when Rathbone experimented with cane in Natal, bringing over four Indo-Mauritians, ‘apparently the first Asiatics to work among cane in Natal’ (Hattersley 1950:119). Rathbone subsequently brought over twenty-five Franco-Mauritian settlers wishing to cultivate sugar.

The Mauritian influence was extended considerably by the recruitment of about a thousand indentured Indians in the 1870s and ‘80s. The Protector’s Report for 1876 mentions’ two to three hundred of such recruits who were chiefly employed in the construction of railway lines’. In the following year 316 Indo-Mauritian recruits arrived in Natal, while for 1878 the figure was 186. The final element in the Indo-Mauritian connection in Natal concerns a few teachers specially recruited in the 1880s to fill the gap for suitable teachers in the schools of the Indian Immigration School Board (Kannemeyer 1943:93).

The subsequent history of Indians in South Africa records the enormous influence of Mahatma Gandhi in their early politics, the fight for a less degrading status and greater economic rewards, as well as the fight against the threat of repatriation. Only in 1961 was permanent citizenship unambiguously guaranteed to Indian South Africans. Problems stemming from inequalities in a segregated society continue today, as they do for the majority of the populace.

Today very few Indians are still to be found in the canelands, and the descendants of the original settlers hold diverse positions, ranging from manual labourers to white-collar workers and entrepreneurs (some of whom themselves own small sugar estates). The financial outlook has improved over the last few decades, together with the level of education, the scale ranging from very poor illiterates, mainly in country districts, to the affluent in a few ‘select’ suburbs. Most traders were able to maintain close ties with India, both economic and social, to the extent of encouraging marriage between their offspring and natives of India, until this was banned by South African law in 1956. The descendants of indentured labourers on the other hand have virtually no contact with the villages their fore fathers left behind. Avisitto India is for most of them a fairly recent experience, made possible by an improved economic position. Those who have recently holidayed in India express mixed emotions about the experience – typically mixing awe at the grandeur of certain aspects of Indian religious life and culture with feelings of alienation from India’s crowded cities and rural poverty.

The many families who chose to return to India in the 1930s and ‘40s did not find it easy to re-assimilate into village life, with its fine caste gradations and other restrictions (Sannyasi and Chaturvedi 1931). The original workers who had migrated to Natal had not all been of the same caste. There were members of all four caste groupings: Brahman(priests), Kshatriya(warriors), Vaishya(merchants), Sudra(workers), though the majority tended to be of a relatively low’ caste. Kuper (1960:7) estimates the latter to be 60 percent.3 The new economic situation that the indentured labou...