eBook - ePub

Kids Having Kids

Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy

This is a test

- 361 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Published in 1997. Adolescent mothers are more likely to encounter a variety of economic and social ills than women who delay childbearing until they are adults. This work is a comprehensive examination of the extent to which these undesirable outcomes are attributable to teen pregnancy itself rather than to the wider environment in which most of the pregnancies and the subsequent child-rearing take place. It also examines the consequences of adolescent pregnancy for the fathers of children, and even more importantly, for the children themselves.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Kids Having Kids by Rebecca A. Maynard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Study, the Context, and the Findings in Brief

Rebecca A. Maynard

Each year, about 1 million teenagers in the United States—approximately 10 percent of all 15- to 19-year-old women—become pregnant. Of these pregnancies only 13 percent are intended. The U.S. teen pregnancy rate is more than twice as high as that in any other advanced country and almost 10 times as high as the rate in Japan or the Netherlands. About a third of these teens abort their pregnancies, 14 percent miscarry, and 52 percent (or more than half a million teens) bear children, 72 percent of them out of wedlock. Of the half a million teens who give birth each year, roughly three-quarters are giving birth for the first time. Over 175,000 of these new mothers are age 17 or younger.

Teen pregnancy has come very much into the public debate in recent years, at least partly as a result of three social forces. First, child poverty rates are high and rising. Second, the number of welfare recipients and the concomitant costs of public assistance have risen dramatically. And third, among those on welfare we see a much higher proportion of never-married women, younger women, and women who average long periods of dependency. No work to date, however, has made a comprehensive effort to identify the extent to which these trends are attributable to teen pregnancy per se, rather than to the wider environment in which most of these pregnancies and the subsequent child rearing take place, or to look at the consequences of teen pregnancy for the fathers of the children and for the children themselves. Kids Having Kids begins to fill this gap.

Guidance from Prior Research

The Kids Having Kids research was undertaken in the context of literature describing trends in adolescent childbearing and factors that lead to or exacerbate these trends and their consequences. Aspects of the literature have helped shape this research. So, too, the results of the Kids Having Kids research underscore the emerging consensus that the poor outcomes observed for teenage parents and their children are the product of myriad factors, among which early childbearing is only one.

Factors Related to the Trends in Teen Birth Rates

The likelihood that teenagers engage in unprotected sex, become pregnant, and give birth is highly correlated with multiple risk factors. These factors include growing up in a single-parent family, living in poverty and/or in a high-poverty neighborhood, having low attachment to and performance in school, and having parents with low educational attainment (Moore, Miller et al. 1995). For example, teenagers living in single-parent households are one and a half to two times more likely to become teenage parents than those in two-parent families (Zill and Nord 1994). Probabilities increase for those with low aspirations and low aptitude test scores. More important, each of these factors increases not only the risk of teen parenthood but also many other negative outcomes, such as poor school performance, weak social skills, and low earnings potential.

Consequences for Adolescent Childbearing

Earlier studies have found that adolescent mothers have high probabilities of raising their children in poverty and relying on welfare for support. More than 40 percent of teenage moms report living in poverty at age 27 (Moore et al. 1993). The rates are especially high among black and Hispanic adolescent mothers, more than half of whom end up in poverty and two-thirds of whom find themselves on welfare. Indeed, a recent study found that more than 80 percent of young teen mothers received welfare during the 10 years following the birth of their first child, 44 percent of them for more than 5 years (Jacobson and Maynard 1995).

This results from a combination of factors, including their greater-than-average income needs to support themselves and their children, lower earning potentials, and more limited means of support from other sources, including male partners. Adolescent mothers have an average of six-tenths more children than do older childbearers, and they have their children over a shorter time span. This fertility pattern both increases their income needs over the long haul and adversely affects the likelihood that they will complete high school and have decent earnings prospects (Nord et al. 1992; Rangarajan, Kisker, and Maynard 1992; Grogger and Bronars 1993; Geronimous and Korenman 1993; Hoffman, Foster, and Furstenberg 1993; Ahn 1994).

Although past literature is consistent in pointing out these poor outcomes for adolescent parents and their children, it is less clear how much of the poor outcomes observed for adolescent parents and their children is directly attributable to early childbearing as opposed to other background and contextual factors common among young mothers. The accumulating evidence suggests that at least half and plausibly considerably more of the poor outcomes can be attributed to factors other than the early childbearing—factors that in many cases may have contributed to the teen becoming a parent (Wolpin and Rosenzweig 1992; Bronars and Grogger 1994; Geronimus, Korenman, and Hillemeier 1994; Haveman and Wolfe 1994; Hoffman, Foster, and Furstenberg 1993). Four such factors are particularly noteworthy.

Single Parenthood. Over time, adolescent mothers have become increasingly likely to be single parents and the sole providers for themselves and their children. Most teen parents are unmarried five years after giving birth. Moreover, fewer than half of the teens who give birth out of wedlock marry within the next 10 years (Jacobson and Maynard 1995). Not surprisingly, therefore, marital status at the time of the first birth is a powerful predictor of subsequent poverty status and welfare dependence, regardless of the age of the woman when she has her first child. More than two-thirds of all out-of-wedlock childbearers end up on welfare, as do 84 percent of young teen mothers who are unmarried when their first child is born. Especially notable about the adolescent mothers is that so many of them give birth out of wedlock and that, when they go onto welfare, they tend to do so for long periods of time—more than 5 of the 10 years following the birth of their first child.

Young mothers, in particular, have limited support either from the fathers of their children or from other adults. Among all unwed teen parents, only about 30 percent of single teen parents live with adult relatives, and less than one-third receive any financial support, including informal support, from the nonresident fathers of their children (Congressional Budget Office 1990).

School Completion. Young teen mothers have exceptionally low probabilities of completing their schooling and thus show weak employment prospects. Just over half of teenage mothers complete high school during adolescence and early adulthood; many who complete high school do so with only an alternative credential—the General Educational Development (GED) certificate (Cameron and Heckman 1993; Murnane, Willett, and Boudett 1994; Cao, Stromsdorfer, and Weeks 1995). Many of those who do complete regular high school have very low basic skills (Strain and Kisker 1989; Nord et al. 1992). The combination of low education credentials, low basic skills, and parenting responsibilities means that teenage parents have limited employment opportunities, primarily restricted to the low-wage market (Moore et al. 1993; Hoffman et al. 1993; Rangarajan et al. 1992).

Social and Economic Circumstances. The logical consequence of these outcomes is high poverty rates, even for those who are employed. Among adolescent mothers, almost two-thirds of blacks, half of Hispanics, and just over one-quarter of whites are still in poverty by the time they reach their late 20s (Moore et al. 1993). The poverty rates for the more than 60 percent of adolescent mothers who live on their own and for those who are not employed are particularly high. Poverty rates exceed the national average even among teen mothers who are employed (24 percent) and those living with a spouse (28 percent) or relative (34 percent) (Congressional Budget Office 1990).

The high poverty rates are accompanied by numerous other life-complicating factors, some caused by the poverty and some contributing to its perpetuation. Teenage parents are disproportionately concentrated in poor, often racially segregated communities characterized by inferior housing, high crime, poor schools, and limited health services. Many of the teens have been victims of physical and/or sexual abuse. For example, recent studies of Washington State welfare recipients estimate that half of those women who give birth before age 18 have been sexually abused and another 10 percent or more have been physically abused (Roper and Weeks 1993; Boyer and Fine 1992). Data from the National Survey of Children indicate that 20 percent of sexually active teenagers have had involuntary sex and over half of those who are sexually active before age 15 have experienced involuntary sex (Alan Guttmacher Institute 1994).

These statistics have been corroborated by recent experiences of paraprofessional home visitors working with a representative sample of teenage parent welfare recipients in three cities (Johnson, Kelsey, and Maynard, forthcoming). In one of these sites, home visitors reported that roughly two-thirds of these teenagers are victims of physical and/or sexual abuse and as many as 20 percent are currently abused or at risk of being abused.

Roles of the Fathers. The male partners of teenage mothers tend not to be teens themselves. Even so, they generally are not a consistent source of support for the teenage mothers or their children. Only 20 to 30 percent marry the mother of their child, and only about 20 percent of the nonresident fathers are ordered by the court to pay child support. Those with orders pay only a small fraction of the award amount (Congressional Budget Office 1990).

Among those fathers whose children end up on welfare, only about one-third have regular contact with the mother by the time of the birth. Another third have intermittent contact, and the remaining fathers have no involvement whatsoever (Maynard, Nicholson, and Rangarajan 1993). Moreover, the father's rate of contact and support declines substantially over time.

Study Design

Unlike most previous research, which compared teenage (under age 20) mothers with those who delay childbearing until age 20 or later, Kids Having Kids focuses on the more than 175,000 adolescent women annually who give birth before age 18 and places primary importance on assessing the likely consequences of delaying their childbearing for an average of about four years, or until they reach age 20 to 21. The particular focus on young teens reflects the strong public concern about the high rate of childbearing among young teens, the vast majority of which results from unplanned pregnancies. Still school age, unlikely to be married, even less likely to be prepared for parenthood, these very young mothers highlight the dimensions of teen pregnancy and parenthood in this country. The delay until age 20 or 21 was chosen as a goal that could plausibly be achieved by policy intervention.

One of the primary purposes of the study was to begin untangling the pathway of early parenting from the intricate web of social forces that influence the life course of the mothers, including the behaviors and choices leading to their adolescent parenting. Disentangling the various types of factors associated with teen childbearing in this way is extremely important for any policy discussion about the benefits to be expected from preventing teen pregnancy.

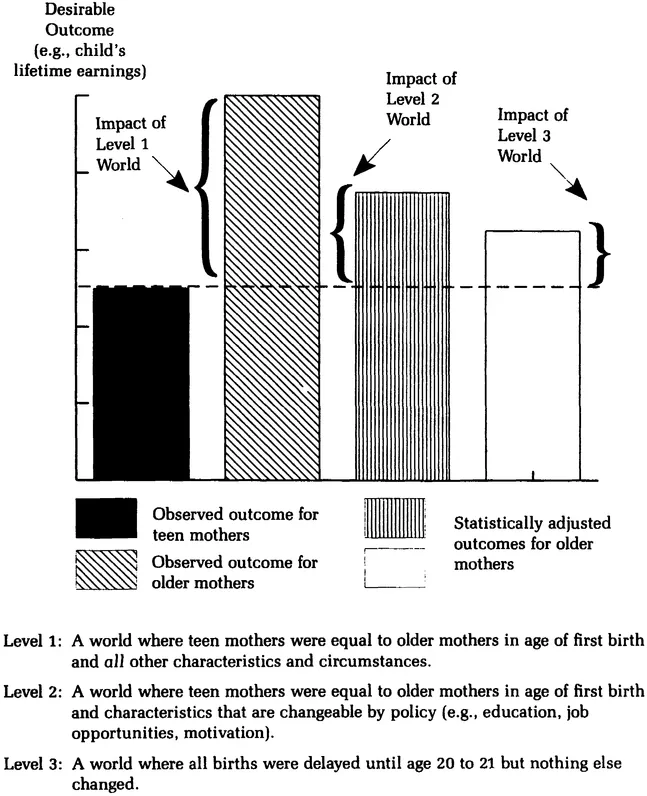

Policy intervention is only justified if there is evidence to suggest that preventing or reducing teen pregnancy and motherhood would indeed improve the lot of the mothers, fathers, and/or children. The analytical strategy for estimating the impacts of different policy alternatives comes down to three types of comparison. Figure 1.1 shows how these comparisons allow us to measure the potential impacts of different "policy" scenarios.

Figure 1.1 HYPOTHETICAL IMPACT ON CHILD'S LIFETIME EARNINGS OF THREE LEVELS OF "POLICY" CHANGE

The most radical of these scenarios would create a world in which all adolescent moms would both delay their first birth until their early 20s and look like their older childbearing counterparts in all other respects. For example, they would have parents with similar levels of education; they would attend schools of similar quality; they would live in neighborhoods with similar economic opportunities and crime rates; and they would have similar cultural backgrounds. Total fantasy, of course, but useful to illustrate the extreme case. This comparison is readily measured and, indeed, the one that tends to shape public opinion. Under this scenario, the benefits of instituting the policy change are equal to the full difference in observed outcomes between early and later childbearers—as reflected in the research reviewed briefly above and measured by the Level 1 world in the figure.

Next, imagine a world in which we had a policy that would delay the first birth and at the same time compensate for or eliminate those differences between adolescent mothers and later childbearers that are susceptible to short-term policy change. Such a change might be a successful pregnancy prevention program that addressed the full spectrum of closely linked factors—such as motivation, economic opportunities, and school quality issues—that contribute to the poor outcomes of early childbearers and that also may have contributed to the early childbearing. The hypothetical benefits of the policy are indicated by the Level 2 world in the figure. The contributing authors estimate the benefits of such a policy by comparing outcomes for adolescent moms with those for later childbearers, controlling statistically for factors not influenceable by the policy package (such as education of parents, race, cultural background, crime in the neighborhood).

Now, imagine that we had a highly effectiv...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Foreword

- 1 The Study, the Context, and the Findings in Brief

- 2 Trends over Time in Teenage Pregnancy and Childbearing: The Critical Changes

- 3 The Impacts of Teenage Childbearing on the Mothers and the Consequences of those Impacts for Government

- 4 Costs and Consequences for the Fathers

- 5 Effects on the Children Born to Adolescent Mothers

- 6 Teen Children's Health and Health Care Use

- 7 Abuse and Neglect of the Children

- 8 Incarceration-Related Costs of Early Childbearing

- 9 Children of Early Childbearers as Young Adults

- 10 The Costs of Adolescent Childbearing

- About the Editor

- About the Contributors

- List of Tables and Figures

- Index