This is a test

- 179 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Combating Social Exclusion in University Adult Education

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Published in 1999, this work suggests that widening participation is not just about changing learner expectations; it is also about changing institutional expectations and practices. "Higher" learning, for example, should include a broader, more inclusive range of knowledge and ways of knowing than at present and criteria for learning achievement should include assessment of "citizenship" as well as linear outcomes.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Combating Social Exclusion in University Adult Education by Julia Preece in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Adult Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | Setting the scene: the wider political context |

In 1991 I was appointed to a university continuing education department. My role was to ‘reach out’ to marginalised social groups in the region and provide short courses which were of university standard. Such groups would be identified largely as people who have minimal initial education and from socio economic groups four and five (skilled, semi skilled or manual workers); in particular, having a disability, being of minority ethnic background or being of retirement age (Sargant 1992, 1997, Metcalf 1993, McGivney 1990, Martin, White & Meltzer 1989). It was a similar project to that undertaken by a number of universities and came nationally to be known as ‘work to counter educational disadvantage’ (UCACE 1992). I was to bridge the gap between ‘non participants’ and the primarily white, middle class and well educated clientele in the department’s traditional programme of short, non-award bearing courses for the general public. The traditional courses were taught by academics, usually on topics which related to the subjects (disciplines) of university departments and were known as liberal adult education (LAE). Although non award bearing, the level of such provision was generally considered to be comparable with the first year of a university undergraduate course. Associated study expectations varied but it was implicitly assumed that people who attended would pursue their interest in the subject with further, independent reading.

Over the next few years funding criteria changed. LAE courses became award bearing. That is each twenty or thirty hour course would now carry credit points for completed assignments, which could be accumulated towards a Certificate. The Certificate was equivalent to the first year of undergraduate study. Courses now needed to be validated by university committees and secure support from relevant ‘cognate’ subject departments within the institution. My work became separately funded in 1995 under a four year initiative to ‘widen participation’ in higher education. The community courses would remain non award bearing, though some carried an optional ‘Access’ level credit (equivalent in standard to A level, the required entry qualification for university study).

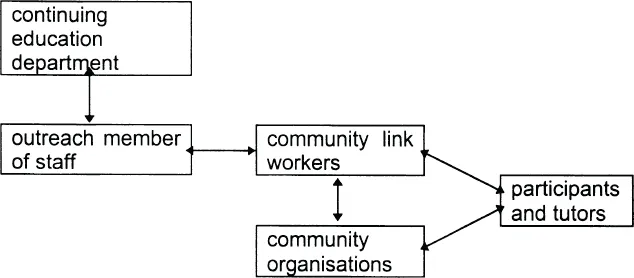

My community education activities succeeded in developing a substantial programme of courses for a wide range of under-represented groups. I adopted a strategy which is well rehearsed by community educators (Ward and Taylor 1986, Lovett 1982, Thompson 1980, McGivney 1990). Figure one shows this strategy as a diagram. It entailed collaborating with small voluntary organisations and local education providers. In some areas I employed a part time ‘role model’ link worker – someone who had a similar social or cultural background to their local community. Course content would be discussed between myself, the link worker and local organisations who had a particular group of participants in mind. The participants’ educational backgrounds would influence both teaching style and curriculum materials. Most of the courses would also be taught by role model tutors, or people who had longstanding credibility or empathy with their learners. Some courses would be taught bilingually, others would be taught by people with relevant experience, rather than particular academic qualifications. Most of the subjects or topics were chosen by community leaders or the participants themselves. The teaching required a critical, analytical approach, but not necessarily with reference to substantial pieces of written work. Courses were rarely advertised other than through locally known routes for members of particular communities and would be provided at a time, place and pace to suit each learner group.

Figure 1 The community education strategy

The majority of participants would attend more than one community course. Often participants shared some sort of social or cultural identity outside of an interest in the course topic. Few of these participants subsequently elected to take part in the department’s main LAE programme or other mainstream provision, and of those that did, most dropped out before course completion. In contrast, the majority of LAE, now credit, participants already had professional qualifications or degrees and partook in the main programme for personal interest or with professional updating goals.

The evolution of two separate strands of provision (the mainstream credit and community courses) raised a number of ideological and philosophical questions within the department, and occasionally outside the department, as to the precise nature of the community activities and their appropriateness for university provision. Discussions with people who had similar roles in other university continuing education departments suggested that these concerns had wider applicability than just within my institution. The study which provided the material for this book developed during a period of intensive debate about differences between the department’s main credit provision and the community courses. This in turn coincided with the department’s own critical period of funding changes and consequent interactions with other parts of the university. The ensuing debates produced some recurrent issues. They are identified here under the following themes:

• the notion of critical analysis in higher education and its relationship to text based learning and teaching

• a perception of the adult learner as a particular kind of person

• the idea of ‘appropriate’ curriculum content and tutors for higher education

• the vision of widening access as a one-way process of bringing people ‘into the fold’

• an assumption that higher education is all-embracing, objective and value-free.

In the process of defending my corner regarding the nature and purpose of the community courses I decided to find a way of identifying what I saw as the cultural differences between the department’s institutional attitudes and those of the learner groups with whom I was working. I involved three different social groups of participants from four geographical locations, plus their role model tutors or link workers. The course participants in particular would talk about their educational experiences and their views concerning university education. I also talked to academics who either had responsibility for similar community courses to mine or were employed to manage or teach the credit programme. In addition, departmental correspondence and other written exchanges within the university provided an academic backdrop, against which the book’s main arguments are placed.

The above exchanges were taking place in a publications arena which was also discussing the nature of higher education, continuing education and its LAE heritage. Influencing some of these debates has been an increasing European focus on the vocational relevance of learning alongside a plethora of policy documents which attach great economic importance to ensuring everyone takes part in learning throughout their life. These debates have consequences for the people who took part in the community provision outlined in this book. The debates and current concepts for higher education therefore need to be rehearsed here briefly. The first issues to consider are: how higher education is perceived by the academic world; and the relationship between higher education and continuing education provision.

Higher education

Barnett, amongst others, has explored some common features of learning for a higher education student. He described these in 1988 as:

The development of the student’s intellectual skills or academic competencies … critical abilities, especially the propensity to be self critical: the ability to analyse and evaluate relevant connections; the willingness to accept the rules of rational inquiry and the self motivation of the students, such as to go on learning and being self critical independently of any intrinsic influence (p.245).

These qualities have more to do with the nature of the learning experience than the matter of subject content. They are essentially about a type of learning which develops a certain type of learner. McNair (1995) has added to this list by suggesting that another essential quality of higher education learning is ‘contesting knowledge’ within certain rules of inquiry:

The central experience of higher education is about learning how such contesting can be done within the established frameworks and gradually learning how to create new knowledge, to challenge established knowledge and test the frameworks for themselves (p.5).

Knowledge in this context is again more about a process of acquisition and use than specific content. These definitions pose both potential and problems for the accounts which follow. The concepts of ‘critical’, ‘inquiry’ and ‘continuous learning’, for instance, seem to be used in the literature as self defining norms for the university experience. Indeed they pervade most discussions about university education, whatever its form. Skilbeck and Connell (1996), for example, confirm that the essence of higher education is its focus on the critical spirit and recognition of the interconnectedness of knowledge, the ability to locate and evaluate information. They also see higher education as developing ‘personal agency’ and self awareness (pp 57–8).

I will argue, however, that university critical thinking takes place in a context which allows only certain view points, approved through authorised texts. New knowledge is allowed but only if it is derived in certain, approved ways – approved by those from within the system (primarily people who are white, male, able bodied and middle class). The contesting of knowledge identified by McNair is consequently self defining as it can only be done from within established frameworks and through the use of peer authorised texts. Knowledge therefore is narrowly defined by, and according to, the social and cultural milieu of those who already create it. Its process of critical appreciation also remains within its own boundaries, so much so that: ‘Those who are situated in a particular paradigm have difficulty appreciating what is not defined as valuable within that paradigm’ (Moghissi 1994: 229).

This notion of higher education, or indeed, formal education generally, is not without its critics. Usher and Edwards (1994) among others, question the historical premis for the established education system which must respond to today’s world of uncertainty, pluralism and change:

Historically, education can be seen as the vehicle by which modernity’s grand narratives, the Enlightenment ideals of critical reason, individual freedom, progress and benevolent change, are substantiated and realised …[as] the self motivated, self directing, rational subject, capable of exercising individual agency (Usher and Edwards 1994: 2).

They go on to suggest that the literature’s definition of the learner needs to be reconceptualised to be more inclusive.

Aronowitz and Giroux (1991) critique more specifically the teaching process and the curriculum. They too are critical of how official texts produce boundaries for knowledge. They emphasise there are different terrains of knowledge and learning which are influenced by time, place, identity and power. They advocate a kind of teaching which: ‘makes central to its project the recovery of these forms of knowledge and history that characterise alternate and oppositional others’ (p. 119). There are therefore signs that people are looking for new ways of weaving a path through modern day demands for increased higher education. Such demands are often tied to a perceived responsiveness to industry and alongside challenges to university elitism so that a new culture of diversity can thrive within the mainstream. The NIACE (1993) policy discussion paper, for instance, emphasises the need to define new knowledge in new ways: ‘The right of particular groups to define what is legitimate knowledge will increasingly be tested from a growing range of standpoints’ (ibid: 15).

These debates are coming under increasing scrutiny as people discuss what kind of higher education is suitable for a mass system in a lifelong learning context. So, for example, McNair (1998), Scott (1997) and Watson and Taylor (1998) place a premium on the higher education teaching process. They emphasise that it should concentrate on encouraging the creation, rather than transmission of knowledge, with a recognition that adults now constitute the majority of the student population. They claim that the new higher education systems will need to be more flexible, completed in smaller units and more related to the world of work. Such systems are also likely to include a stronger focus on promoting general, transferable, higher learning skills such as the ability to apply knowledge and understanding (Cryer 1998). In the modern, unpredictable and uncertain world, knowledge rapidly gets out of date – hence the need for adaptability skills and systems which accommodate re-entry into study for all parts of the population.

The new world order for higher education, however, is rooted in a philosophy and tradition which has already defined what counts as knowledge – and even what are acceptable ways of acquiring new knowledge. This philosophy and tradition particularly underpins university adult education and takes its legacy from an embedded notion of liberal adult education (LAE). In the older universities this is provided through designated adult education departments. Although the nature of this provision in its purest sense is fading rapidly its rationale for what counts as a suitable university curriculum lingers on. It heritage therefore is still worth glossing over.

The liberal adult education heritage

Fieldhouse (1996) claims that the form, if not the content, of LAE can be traced back to early, 19th century working class adult education discussion groups which set the precedent for adult education as a dialogic, democratic exchange. These classes, he says, distinguished LAE from the more didactic tradition of state controlled vocational training.

Liberal education, taken in its broadest sense, was regarded as non partisan and pluralist in approach. Its aim was to avoid injudicious bias towards localised interests, to avoid a left wing slant, to work according to only recommended books and authors. The educational aim, as Raybould (1964) argued, was: ‘more than the imparting of accurate information’ (p. 130). The emphasis was on learning as a cultural experience which was independent of social purpose and value free – but a learning which trained the mind to think and reflect. Elsey (1986) described this learning process as: ‘examining ideas from different perspectives and dispassionate inquiry’ (p.70).

It is these concepts which seem to have generated most debate. For instance, the possibility of ‘dispassionate inquiry’ as an exercise in objective analysis is challenged for its achievability at all: ‘It is arguable that to be neutral or objective in the sense of being value-free is an impossibility for an adult educator’ (Fieldhouse 1985: 23); and sometimes for its deliberate use as a: ‘smoke screen to discriminate against Marxist and other socialist perspectives’ (Fieldhouse 1985, introduction).

The rationale behind both claims seems embedded in an ideological conflict resulting from the growth of capitalism and alternative working class initiatives to challenge the social order upon which universities as elitist and privileged institutions were built. It is commonly argued, for instance (Simon 1990, Westwood and Thomas 1991, Fieldhouse 1996), that independent initiatives in the early 1900s to develop a curriculum of relevance for the working class were challenged as subversive and Marxist. The state’s supported creation of the WEA in 1903 consequently emerged as an alternative higher education arm for the working classes. But they were granted state funding on condition they only accepted university lecturers as a teaching resource. This was in order to provide a ‘stable’ curriculum in competition with the more grass roots funded National Labour Colleges which developed around the same period. The views of the colleges were delegitimated as biased and partial, in contrast to the intellectual, and higher rationality, of abstract university thinking. The development of university LAE must therefore be understood from the perspective of its originators – a philanthropic minority of the ruling class – which necessarily had a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Liberal education’s position of objective and political neutrality is perceived by some as resistance to social action, because non-action and passive neutrality inevitably support the prevailing orthodoxies in society, which in themselves have built the system and its power structure (Thompson 1980). Consequently, it is argued, the liberal tradition itself already starts from a position of bias, whose own rules prevent a more equal distribution of values. A more constructive form of learning, for instance, might include enquiry followed by direct action, drawing on people’s own experiences, rather than simply acquired written information (Thompson 1980, Jackson 1980).

Whilst LAE retains its philosophical heritage in much non vocational adult education the past forty years have seen a continuous shift in policy and provision towards a vocationally oriented focus and more instrumental approach to learning. As a result university versions of vocational education have adopted a hybrid of liberal adult education, but within a more product oriented context. Indeed, the 1970s saw international organisations such as the OECD and UNESCO producing reports which created the impetus for a lifelong learning agenda. Their emphasis was on technology and vocationalism as a means of global integration (Hamilton 1996, Korsgaard 1997, Tuckett 1997). European White Papers have focused on promoting social inclusion through lifelong learning as a skills updating process whose goal is to develop flexible, mobile young people, able to adapt to a fast changing and increasingly interactive world (DGXXII, 1995). More recently the British Government’s own Social Exclusion Unit has proposed strategies for neighbourhood renewal with an emphasis on education and training initiatives (1998).

Since 1995 UK LAE has lost its historical place as a distinctive, non award bearing feature of university part time study. A relatively recent term has been introduced to reflect the image of university adult education as an updating process. Continuing education (CE) is becoming almost synonymous with lifelong learning and both terms are used to describe current day university departments which make separate part-time provision for adults. CE’s broad definition is generally understood to refer to part-time study for learners: ‘other than those progressing directly to higher education from full time initial studies’ (Slowey 1997: 196).

The question of who participates in the university experience, however, has remained problematic. Late twentieth century statistics regarding working class participation of all ages in higher education have changed relatively little since those early attempts via universities and the specific bridging remit of the WEA. In spite of an increased expansion of mainstream higher education from fifteen percent of the population to thirty percent in the last thirty years, the social class make up of learners has barely changed, particularly among adults (Sargant et al 1997, Dearing 1997). There is an increasing literature which challenges the university’s abdication of responsibility for this trend, especially from the viewpoints of under-represented groups. Much of the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Setting the scene: the wider political context

- 2 Who has authority to know?

- 3 That’s not a university subject

- 4 ‘We don’t really belong’

- 5 Setting the local scene - the learner contexts

- 6 Excluded versions of truth

- 7 The creation of social exclusion

- 8 Combating social exclusion: being inclusive about difference

- 9 Changing identities

- 10 Combating social exclusion re-assessed

- 11 Conclusions and recommendations

- Bibliography

- Index