![]()

1 Modern Mining and Its Challenges

1.1 INTRODUCTION

During the last decade, the mining industry has undergone major developments, which are most evident in improvements in safety. For example, the current safety levels of the Swedish mining industry are almost the same as that of manufacturing or construction industry in Sweden (Swedish Work Environment Authority 2016). At the same time, Elgstrand and Vingård (eds. 2013, p. 6) reported that ‘Where reliable national statistics exist, mining is generally the sector having the highest, or among 2–3 highest, rates of occupational fatal accidents and notified occupational diseases’. In other words, notwithstanding significant improvements, work still remains to be done. In addition to this, in many countries, the mining industry faces a different type of challenge: that of ensuring the supply of a qualified workforce in the future. The mining industry is not attractive enough to entice skilled and young people. The problem is two-pronged: (1) the current workforce is ageing and is not being replenished (Hebblewhite 2008; Oldroy 2015) and (2) the changing nature of mining work will require a new set of skills and competences, such as abstract knowledge and symbol interpretation (Abrahamsson and Johansson 2006). Those who possess this knowledge are likely to be found in a population that may be even less interested in employment in mining. Lee (2011, p. 323) framed the problem as:

A shortage of qualified miners in all types of positions is a critical issue in many countries and regions of the world. During the last decades, as mining declined, the work force was not replaced. … many companies are unable to meet demands because of the severe labor shortage. People currently employed in mining are retiring, and there is a lack of younger people to fill the vacancies.

Hutchings et al. (2011) also indicated the difficulties the mining industry has in attracting employees with appropriate skills. They argued that organizations should give greater attention to strategies that attract and retain skilled employees. To solve the problem, the mining industry employs two primary strategies. On the one hand, the mining industry tends to deal with this issue at a strategic level. Aiming to attract skilled workers, the industry promotes the advantages of working in mining, such as career development, high salaries, and travel opportunities (cf. Randolph 2011). On the other hand, the mining industry is techno-centric and seeks technological solutions to problems (cf. Albanese and McGagh 2011; Hartman and Mutmansky 2002; Lever 2011). Recently, however, the workplace has been recognized as important in facilitating attractive jobs. Lee (2011) identified work organizational strategies for increasing the attractiveness of the industry: avoiding long hours and shifts that do not match modern lifestyles, for example, and upskilling and multi-skilling personnel. Similarly, Johansson et al. (2010) identified safety, the physical and psychosocial work environment, and social responsibility as important areas for increasing the attractiveness of jobs in the mining industry. Workplace-level interventions can, according to Hedlund (2006, 2007) and Hedlund and Pontén (2006), increase the attractiveness of industrial jobs. Yet, workplace-related changes to increase work attractiveness remain a rare strategy within mining companies and is in general under-investigated. It is here that we see the purpose of this book: it offers guidance for designing more ergonomic, safe, and attractive mining workplaces.

The concept of ‘attractiveness’ (although explored extensively in Chapter 2) needs additional clarification here. In one sense, ‘attractiveness’ widens the concept of health and safety. In the other, it is a specification of the ergonomics concept. In the first sense, modern methods of accident prevention are holistic and take into consideration the full span of human, organizational, and technological aspects (cf. Harms-Ringdahl 2013). The safety aspect of mining is very important and should always come first. However, a completely safe mine is not necessarily attractive. But we argue that an attractive mining workplace is by necessity safe and that attractiveness can contribute positively to safety. We will try to illustrate why this is, and by doing so, we aim to show how modern safety and accident prevention approaches do not necessarily consider these topics.

Regarding ergonomics, the topics we cover are in some sense all a part of this field. In part, this book exemplifies the application of theories of ergonomics to mining workplaces, but primarily it illustrates how these theories and human-centric design facilitate the creation of attractive mining workplaces. By presenting the concept of ‘attractiveness’ as a specification of ergonomics, we mean that it gives guidance on which theories and their applications contribute to attractive mining workplaces; as theories of workplace attractiveness are based on theories of ergonomics (cf. Åteg et al. 2004; Hedlund 2007), the factors that contribute to workplace attractiveness represent a specific subset of theories of ergonomics.

The topic of this book is not solely about securing a future workforce, though; like the discipline of ergonomics, it is also very much related to productivity and efficiency (cf. IEA 2017). Attaining ergonomic, safe, and attractive workplaces should be an objective in itself, but there are several other advantages to it as well. These include lower costs, higher productivity, improved quality, and so on. Research has shown that there is a connection between safe and healthy workplaces and those that are productive and efficient. For example, Neumann and Dul (2010) compared 45 scientific studies and found that 95 per cent of them showed a connection between human and system effect: if system performance was poor, then employee well-being was also poor, and if system performance was good, then employee well-being was also good. Another study (ILO 2006) found that there is a correlation between competitiveness and accidents at work. That is, countries with lower levels of occupational accidents are generally more competitive.

Of course, these topics should not be reduced to solely economics. And nor does working with them not incur costs. Health and safety, for example, cannot be attained free of cost: investment is needed to create and maintain healthy and safe workplaces. Our argument (and we are far from the only ones to argue this) is that spending money on health, safety, and related topics now saves money in the future. According to the American Society of Safety Engineers (cited in Blumenstein et al. 2011), for example, every dollar spent on prevention can save three to six dollars in loss avoidance.

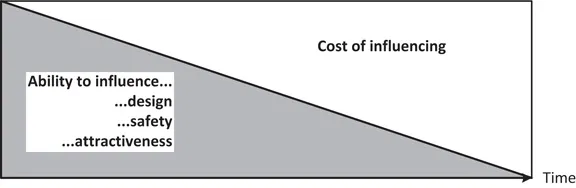

There are other aspects to this as well. It is during planning that the most important decisions regarding work environment and safety are made, that is, when deciding on mining methods, technology, work organization, etc. To be able to influence the aspects relating to ergonomics, safety, and the attractiveness of the workplace, they have to be considered at the early stages of a project. Figure 1.1 illustrates this relationship as it is commonly expressed. One aim of this book is to give an understanding of how to work with these issues early.

FIGURE 1.1 The ability to influence and cost of influencing design, safety, attractiveness, and so on over time.

To summarize, McPhee (2004) put it clearly. He argued that mining is similar to other heavy industries, and the same principles of design apply in mining as in other industries. While top priority is still assigned to mining disasters and fatalities, the emphasis is changing to include a broader health and safety focus. But, he argued, ‘there still appears to be a poor understanding about the contribution of ergonomics to mining, the range of factors that it includes and how these might be addressed’, and that the different position of the mining industry is due to ‘the different systems that have arisen specifically for mining and that may need to be accommodated through planning and design’ (McPhee 2004, p. 297). He saw several emerging issues in ergonomics in mining. For example, there is a change in work practices and a drive for increased efficiency. And some of the practices adopted by the mining industry are at odds with the need to improve the health and safety in general (McPhee 2004). This book takes a special interest in these emerging, as well as traditional, issues and discusses how they can be accommodated through planning and design.

1.1.1 THE POSITION, PURPOSE, STRUCTURE, AND CONTEXT OF THE BOOK

Currently, there are several books on health, safety, ergonomics, and related issues in the mining industry. Some seminal works include Horberry et al. (2011, 2018), Simpson et al. (2009), and Laurence (2011). This book, however, takes a wider perspective. On the one hand, it focuses on the wider issues of attractiveness. As noted, this is not necessarily the same as safety or ergonomics. On the other hand, this book focuses on workplaces and places special attention on workplace-level strategies and practices. In doing so, we try to accomplish two things. First, we give an account of issues – particularly of a social nature – that modern mining is faced with and their nature. Second, we propose two approaches to address these issues operationally and more strategically, respectively. This is not to say that the aspects are unrelated or separate. On the contrary, we hope to show that it is because the issues are what they are that they require the proposed approaches. We do not, however, offer unequivocal advice. The situation in mining, we argue, is context-dependent. And the best alternative in one context may be the worst in another situation. Thus, our strategy is to provide basic knowledge that we hope will help in making the right decisions based on facts regarding the conditions in each unique situation.

The book is structured as follows. In this chapter, we focus on the characteristics of modern mining together with some of the challenges it faces and the present trends. In the Chapter 2, we focus on the concept of attractiveness, and how it relates to other fields of study. Chapter 3 focuses on injuries and ill health in mining, while Chapter 4 focuses on mechanization, automation, and new technology. In these two chapters, we try to show how these issues go beyond traditional ‘engineering’ problems: that they are problems of a social nature as well. Chapter 5 covers work organizational issues in mining. Special attention is given to how some modern organizational ideas can be adapted to mining, and their role in addressing work organizational issues and related challenges. This constitutes the first part of the book. The second part focuses on how to generally approach and address the issues brought up in the first part; in Chapter 6, we cover some of the principles behind work environment management, while we in Chapter 7 focus on how to work with iterative, user-centric design and planning methods.

This book also represents an attempt to introduce to mining ways of thinking and methods that are common in other industries. In this, the mining industry poses an interesting challenge because it is not solely a process industry, construction industry, and so on. It encompasses all these things. As an example, commentators in the process industry have argued for ‘operations centre’ concepts. This is not fully possible in the mining industry because it includes aspects from several other industries. The design of mining workplaces must be carried out in way that not only considers all these factors, but that also makes them work together. Additionally, the perspective introduced in this book includes the fact that mines, new mine levels, and so on represent significant investment. They are not realized overnight and can require several years of planning. Therefore, making mining more attractive, safe, and ergonomic in existing workplaces requires as much work as workplaces of the future do. At the same time, it is not enough (and sometimes not even possible) to work with these topics in the operating stages of a mine or development project. These topics require attention from the very first project stage to the very last, which is why these stages are given specific attention in this book.

Finally, in this book we use many examples and experiences from Sweden. On the one hand, we believe that the Swedish and Nordic perspective stands to offer a lot in this context. On the other, there is plenty of Swedish language research that does not reach an international audience. As a result, several successful examples stemming from the Swedish context have not been showcased outside of Sweden. Sweden also has a long tradition of mining with plenty of research looking at its organization, labour, technological development, and so on. Thus, a secondary purpose of this book is to disseminate this knowledge to a wider audience. To this end, we next look at the development of Swedish mining company and how these experiences should be applicable to other mining companies as well.

1.2 HISTORICAL AND MODERN MINING

Mining is a diverse activity. Elgstrand and Vingård (eds. 2013) described the situation in 16 mining countries. At one end of the spectrum, there is the artisanal, small-scale, and sometimes illicit mining in, for example, Ecuador and the Democratic Republic of Congo that persists under poor and dangerous working conditions. At the other end of the spectrum is the highly mechanized and automated mining of, for example, Australia and Sweden. Of course, before becoming modern, high-tech operations, these mines were also characterized by frequent accidents and poor work environments. In this section, we review this type of development in the mining industry. The reason for doing so is that this development has included technical, organizational, administrative, and other changes; some of these are very closely connected to the topics addressed in this book. Through this review, we hope to showcase the breath of possible developments in mining.

1.2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF A SWEDISH MINING COMPANY

We use a Swedish mining company to represent one of the evolutions of Swedish mining. Though the implication of the Swedish context should not be overlooked (for example, in terms of legislation, worker rights, culture, and so on), we hold that the developments themselves are neither necessarily unique to the Swedish context nor to a particular company. That is, we believe that the developments presented here have also occurred in several other companies. A lot can be learned, then, by studying these developments.

Johansson (1986) described work and technology in a Swedish underground iron ore mine between 1957 and 1984 in detail. He noted that in 1957, work in the mine utilized several machines, but the need for heavy manual labour was still significant. (Figure 1.2 depicts drilling around this time.) The degree of mechanization and technological sophistication was asymmetric throughout the mine. For example, the production activities used modern and sometimes semi-automated machines, while development work still utilized older types of machinery involving manual operations. (Figure 1.3 depicts a loader that was used in development work during this period.) The semi-automation consisted in, for example, partial automation of drill rigs where the operator had to feed drill steels to the drill. Work was organized into teams that were responsible for entire production cycles and planning. The company considered itself to have made use of technological development to improve work conditions and to increase productivity. Additionally, due to the demands for labour during this period, they implemented progressive staffing policies. At that time, the director of the company was illustrated as saying:

In question of salaries, pensions and working hours, our company’s miners should be better off than any other comparable group of industrial workers in Sweden … The development that has led to the rapid improvement of working conditions with regards to spaces, ventilation, illumination, and so on, and to a lighter and less dangerous work, is important. And in the lo...