eBook - ePub

Maintaining a Satisfactory Environment

An Agenda For International Environmental Policy

This is a test

- 82 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Maintaining a Satisfactory Environment

An Agenda For International Environmental Policy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is an outcome of a seminar organized to discuss an agenda for saving the environment of Europe. It covers the issues in international environmental policy and explores how to achieve an integration of environmental policies with other governmental policies and through economic instruments.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Maintaining a Satisfactory Environment by Nordal Åkerman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Several Approaches to the Analysis of International Environmental Policy

Volker von Prittwitz

Introduction

Foreign policy and international relations have traditionally focused on issues such as military force, political power, and economic relations. Facing rapid technological change, new risks and an alteration of value-patterns, we are experiencing the rise of a new issue of international politics: environmental affairs. The systematic analysis of this issue is based on certain approaches, that is, the analysis refers to certain concepts, formulates questions in a systematic way, produces certain criteria for choice of variables and estimation, and forms certain hypotheses. There are six approaches which I consider to be particularly relevant:

- * the discussion about the optimal institutional level of action (levels approach),

- * the foreign environmental policy,

- * the environmental mediation,

- * the international regimes,

- * the structural system, and

- * the global commons approaches.

I will briefly describe these approaches and outline some of their implications for practical environmental policy. The final section contains considerations about how the approaches are interrelated along with conclusions for further research.

The Search for the Optimal Institutional Level of Environmental Policy

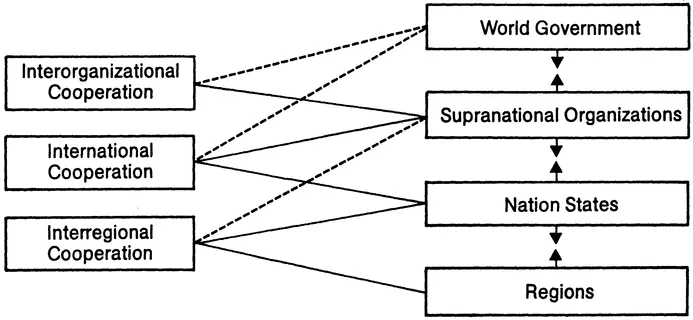

The political process always occurs on one car more institutional levels, such as local, regional, national, supranational and global levels. The question is on which level environmental policy should be established and enforced and how environmental activities on different levels can be optimally linked to one another.

The starting point of this discussion is to establish that environmental problems are transnational in nature. This has been emphasized in many studies in which the global dimension and increasing importance of the environmental crisis is stressed. Well-known examples of this "global view" literature are Dennis L. Meadow' Limits to Growth (1972) and the Global 2000 Report to the U.S. President (Council on Environmental Quality 1980). Other early work of this kind stems from Harold and Margaret Sprout (1965) and Lynthon Keith Caldwell (1972, 1973). The establishment that "environmental problems don't stop at national boundaries" has meanwhile become a standard formula in the environmental discussion.

Some authors have drawn an extreme conclusion from the transnational nature of environmental problems. They argue that only a world government could handle the ecological crisis. In 1980, Felix Ermacora, an Austrian specialist in public and international law, published an outline of a future world government which would have the task of protecting peace and human rights, providing for the nutrition of the world population, and the management of nuclear energy production (Ermacora 1970:1200). Plans for an ecologically oriented world government with features of an ecodictatorship were proposed by the East German philosopher Wolfgang Harich in 1975. Last but not least, Garry Davies, "world citizen No. 1" since 1948 who has sold about 200,000 world passports of his world government, is aware of the global nature of the environmental issue (Die Welt, 11/19/1987, "Der Weltburger No. 1 will Prasident werden").

However, practical attempts to establish a global government have not gone beyond the institutionalization of a political stage for conflicts between national actors (see the political process in the United Nations). Therefore, the demand for a world government has not up to now played a relevant role in the public and in the scientific discussion. In fact, international cooperation, i.e. contacts between nation states, has been the main form in which international environmental policy has been implemented. This cooperation between (at least formally sovereign) nation states has often been proclaimed by international organizations such as the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), the Economic Commission of Europe (ECE) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The main advocates of such cooperation are countries which are interested in using international contacts without being endangered by the force of a strong supranational institution which might affect their sovereignty.

A step from the environmental cooperation between sovereign states towards the establishment and enforcement of supranational programs has been made in the European Community. To an increasing extent, a supranational environmental policy is being developed in the EC. A basic instrument of this policy is the environmental directive, which is binding for the member states. These directives often contain environmental standards (on air and water pollution, noise etc.) which have a double effect: they give the impression of ensuring environmental quality and because of their uniformity make it easier for business firms to export and import goods. Environmental policy of this kind is, in the long run, a means of economic and political integration on a supranational level. Such "European Environmental Policy" is finding more and more advocates (Bothe 1979; von Moltke 1979; Ofterman-Clas 1983; von Weizsäcker 1985; Gündling and Weber 1987; Teunissen 1988; Simonis 1988). It can be expected that economic and political pressure for the harmonization of environmental norms will increase even more through the planned unified European market.

However, supranational standardization of environmental demands does not only have advantages. If environmental standards must be uniform for all participants, they tend to be fixed at the level of the smallest common denominator. Once fixed, they represent a kind of "pollution allowance" or a license for the consumption of natural resources up to the fixed limit. Thereby, dynamic forces of environmental competition tend to be suppressed. Under certain conditions, countries willing and able to do snore for environmental protection than required by a standard are even hindered from doing so. Another sometimes ecologically unsound implication of standard setting at high institutional levels is the growing distance between the regulators and those affected by the regulations. Fine ecological and social structures are not met; connections between program setting and practical action get lost; and the people have no influence on decisions that affect their lives.

In view of these problems, it is not surprising that there is a traditional link between regionalism and environmentalism. Many people consider nation states and supranational institutions to be the enforcing agents of an alienating and threatening civilization (Mayer-Tasch 1985:138). The alternative is life in one's own native region, apart from and possibly resisting the influence of a nation state and supranational institutions (Zellentin 1979: 122/123).

Figure 1: The Levels Scheme of International Environmental Policy

A preference for national rather than supranational standard setting ("Nationaler Alleingang") is an argument that comes up virtually everytime a foul international compromise which will burden the environment is outlined. With this in mind some authors have formulated a general critique of the internationally uniformed environmental policy (Zellentin 1980; Weidner/Knoepfel 1981).

In a synopsis of what we have discussed, we see that environmental policy is in a tense situation between two poles: the necessity to cope with transboundary large-scale environmental problems, and the necessity to protect the small-scale environment in certain places in the best possible manner. One conclusion that could be drawn is to recommend active involvement on each conceivable level. An example of this concept is given by the environmental organization "Greenpeace", which fights environmental destruction at global (impressing the world public), supranational, national and local levels (with spectacular actions, distribution of leaflets and routine work).

But the main conclusion to be drawn is, in my opinion, that we must search for an optimal balance and combination of environmental responsibilities. Bungarten (1976, 1978), von Moltke (1979) and Weinstock (1983) analyze European environmental policy as a complex structure consisting of supranational, national and subnational elements. Under the question "Only one European Environment?," Weinstock interprets the concept of environmental harmonization in explicit contrast to ideas of uniformity. According to Bungarten, three economic criteria can be applied in search for the optimal level of decision: use of the economies of scale, minimization of external effects, and harmony of interests through close contact to the citizens (Bungarten 1976: 111). In order to handle transboundary environmental problems, activities on different institutional levels are usually necessary. The optimal choice and combination of levels varies for each particular issue. For example a global issue such as the ozone layer problem requires activity on a global scale involving producers and consumers of chlorofluoro-carbons, as well as activities on lower levels with emphasis on the national level. Regional problems often need decisions on the level of bilateral cooperation in frontier regions, as well as on national and regional levels (OECD 1979b; von Oppeln 1989).

Scharpf has stated that interlocking institutional structures between the national and subnational as well as between the supranational and the national levels can be a "trap," if decisionmaking responsibilities on different institutional levels hamper one another (Scharpf et al 1976, Scharpf 1985). He favors the decision-making procedure of problem solving over the bargaining between political actors on different levels. That is, optimal solutions for all participants should have more importance than single interests. The transition to problem solving will be facilitated by three conditions: 1) awareness of a common threat and/or common vulnerability, 2) hegemony of one participant, 3) institutional separation of problem solving and decisions on distribution (Scharpf 1985). In the framework of environmental politics, the awareness of a common threat for all participants is particularly relevant. However, this concept, known as the Joint Decision Trap, does not reflect that bargaining processes are often the most exact and sensible expression of complex needs. In every case of environmental policy, the level on which decisions should be taken is an open question.

Foreign Policy and Environmental Affairs

Foreign and environmental policies differ in some respects: whereas foreign policy is a well-established, traditional political field, environmental policy has only recently developed and represents a brand new political issue in some countries. According to widespread opinion, foreign policy is based on common interests and values in a country; in contrast, environmental policy often seems to be a field in which particularly sharp interest differences exist. Foreign policy is supposed to be about high politics where the application of power and even force is legitimate? environmental protection is often thought to be a technical business. And last but not least, in many countries, environmental policy has developed through a social movement ("from below"), whereas foreign policy ranks as a sphere of diplomats and statesmen who act high above the common people. For these reasons environmental and foreign policies remained separate for a long period of time.

Now, the situation has begun to change: Ecological issues have shed their image of being the exclusive topic of a few ecologists, and environmental awareness has grown. Environmental protection is more and more being recognized as a shared responsibility. Along with these developments, the understanding of what constitutes national security has broadened. In the public perception, national interests such as land protection, economic well-being and national power increasingly includes ecological and health aspects (Myers, 1982; Müller, 1987).

Consequently, foreign policy is growing to incorporate policy on environmental issues, foreign environmental policy (Prittwitz 1983b). Concepts and conditions of this policy, sometimes also called "Environmental Diplomacy" (Carroll 1983), need to be discussed. Foreign environmental policy can be defined as all the activities of a nation state or another representative body directed towards one or more foreign actors which are designed to pursue environmental goals. Such goals might immediately include the protection of environmental quality within the country concerned. As any environmental destruction or environmental risk in the world potentially affects the ecological balance and people's health, foreign environmental policy also refers to the goal of achieving better environmental conditions in general.

Up to now, the scientific discussion has focused on interest patterns, strategies, organizational structures and process typologies of foreign environmental policy (Carroll 1983; Prittwitz 1983a, 1983b, 1984, 1986a, 1986b; Brunowsky and Wicke 1984, Mayer-Tasch 1985, 1986, 1987; Scharinger 1985; Strübel 1986, 1988; Voigt 1987; Björkbom 1987; Bowman 1987; Tudyka 1988). Here, I will only deal with interest patterns and possible strategies of this policy.

Traditionally, two environmental interests have confrontedone another. Anyone who benefits from a polluting activity (including the consumption or destruction of a natural resource) is interested in continuing this activity and keeping costs for environmental protection low (polluter interests). Anyone who suffers f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- SEVERAL APPROACHES TO THE ANALYSIS OF INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY

- ENVIRONMENTAL DAMAGE BALANCE SHEETS

- SOME BASIC ISSUES IN INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY

- TOWARDS A BETTER INTEGRATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL, ECONOMIC, AND OTHER GOVERNMENTAL POLICIES

- List of Contributors