eBook - ePub

Economic Policy, Financial Markets, And Economic Growth

Benjamin Zycher

This is a test

- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Economic Policy, Financial Markets, And Economic Growth

Benjamin Zycher

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The links between economic policy and economic growth are simultaneously obvious and obscure, with many factors interacting to influence the overall process. The list of relevant parameters affecting economic growth of interest to scholars and policymakers is lengthy and expanding. Although the importance of government policy is widely recognized,

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Economic Policy, Financial Markets, And Economic Growth by Benjamin Zycher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part One

Capital Markets, Capital Formation, Savings, and Economic Growth

Introduction

That economic growth is affected by myriad factors is a truism, and the list of relevant influences of interest to scholars and policymakers is lengthy and expanding. In particular, the importance of various government policies is recognized widely, but the relative magnitudes of their effects and their respective absolute impacts upon growth are difficult to measure. Even the direction of impact of some policies-that is, the issue of whether their net effects are positive or negative-is in dispute.

The chapters in this section, by Robert J. Barro and Jack L. Carr, illustrate divergent approaches to analysis of the economic growth effects of government policies. Using straightforward econometric techniques, Barro examines factors likely on a priori grounds to affect the rate at which individual incomes in poor regions or nations grow relative to those in wealthier areas. This analysis of income “convergence” yields several interesting findings, among them an empirical estimate of the long-run effect on the growth of individual incomes yielded by greater resource allocation by government. Two findings that are more surprising are the ambiguity of the effect of individual income upon the saving rate and the suggested small impact of international trade upon income convergence.

Barro’s chapter raises a number of interesting questions, foremost among them the issue of why government policies affecting economic growth vary so greatly among nations. That in a real sense is a restatement of a very familiar public choice issue: Why does government behave as it does, and how can the incentives shaping government behavior be structured to encourage policy choices consistent with stronger growth in individual well-being?

Other interesting issues emerged during the course of the general discussion at this first session of the MIJCF conference. Barro includes investment (as a share of GDP) as one variable affecting the growth of individual income, but does not separate the relative impacts of private and public investment. (The chapter by William A. Niskanen in Part IV of this volume addresses that issue in part.) Another interesting comment dealt with efforts to aid the economic transition and growth processes in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe; what can the West do to promote political stability and the transition to capitalism? In this context, further refinements of Barro’s work perhaps ought to include some measure(s) of foreign aid, as an empirical test of the benefits often purportedly engendered by such policies. This has direct relevance to U.S. domestic policy, because federal aid to inner cities in many respects is similar to U.S. foreign aid policies, and the long-run impacts of those policies in terms of economic advancement are ambiguous at best.

In Chapter 2, Carr recognizes the substantial difficulty with which existing economic models of growth actually explain observed differences in growth, both across nations and over time, and then discusses some implications of two general hypotheses about the origins of policies affecting growth. One hypothesis is the “public interest” theory of policy: government policies are adopted in efforts to further some conception of the public interest (or to negate the adverse effects of various types of market failure). The second is the “private interest” theory: government policies are the result of competition in political “markets” for the subsidies, favors, and protection from competitors demanded by interest groups.

The problem of explaining government policy choice is crucial in the growth context because the incentives shaping the choice and implementation of economic policies ultimately determine their net effects upon growth. To the extent that market failures of various types reduce national wealth, to the extent that the reduction is significant, and to the extent that market forces inherently are unable to reduce such adverse effects, the critical question remains: Are there reasons, whether conceptual or empirical, to believe that government action can be expected to yield net improvement?

After a brief discussion outlining some reasons for skepticism about the benevolence of government policy-making, often assumed implicitly but rarely justified, Carr examines the public and private interest rationales in the context of government deposit insurance for banks. The public interest rationale stems from the social costs created by “rational” runs on banks when individual depositors cannot distinguish easily between problems affecting a given bank and those affecting the banking system. Deposit insurance would prevent such runs, thus preserving the stability of the banking system. In the private interest view, on the other hand, deposit insurance provided by government is a device with which small banks can attract deposits on the same terms as large banks, despite the greater inherent riskiness of the former. Deposit insurance in this view, therefore, is an implicit subsidy scheme emanating from interest group competition, and so is likely to reduce national wealth by distorting the allocation of resources-in this case, financial capital.

Carr concludes that the histories of deposit insurance adoption in Canada and the United States are consistent with the private interest model of government behavior. This finding is important: if consistent with findings derived from empirical examinations of other policies, it suggests that government policies in general, whatever their respective rationales, systematically may yield effects upon economic growth that are negative on net.

Carr points out that deposit insurance provides incentives for excessive risk taking and other adverse behavior. One interesting point raised in the general session discussion concerned efforts by government to limit such ensuing adverse effects; an example noted by Carr is the legal limit on interest paid on insured deposits. The discussion centered upon efforts by government to reduce such negative ancillary effects of policies, and whether these efforts inherently are self-limiting or endlessly expansionary. In order to regulate, can the government focus be narrow, or must it expand continually as markets respond behaviorally to existing rules? That question has not been answered, but it is central to the examination of government and its effects upon economic growth.

1

Economic Growth, Convergence, and Government Policies

A key issue in economic development is whether economies that start out behind tend to grow faster in per capita terms and thereby converge toward those that began ahead. This convergence property seems to apply empirically for economies that have similar underlying structures, such as the regions of the major developed countries or among the OECD countries but not for a heterogeneous collection of countries that includes the poor nations of Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. One reason for the failure of convergence in this broad context is that countries are effectively heading toward different long-run targets for per capita income. These targets depend on government policies in areas such as taxation, protection of property rights, and provision of infrastructure services and education. The targets can also vary because of factors that governments cannot readily influence, such as underlying attitudes about saving, work effort, and fertility, and the availability of natural resources. For a given long-run target-determined by government policies and other factors-the convergence tendency depends on the speed with which an economy approaches this target. This speed turns out empirically to be similar across economies, such as a broad cross-section of countries, that differ greatly in other respects. Conceptually, the speed of convergence depends on such issues as diminishing returns to capital, the behavior of saving, the mobility of capital and labor, and the diffusion of technology from leaders to followers.

I begin this chapter with a discussion of some empirical evidence on economic growth, especially as it pertains to the convergence question. Then I relate these facts to theories of economic growth and make inferences for the role of government policies.

Some Empirical Evidence on Convergence

Regional Data

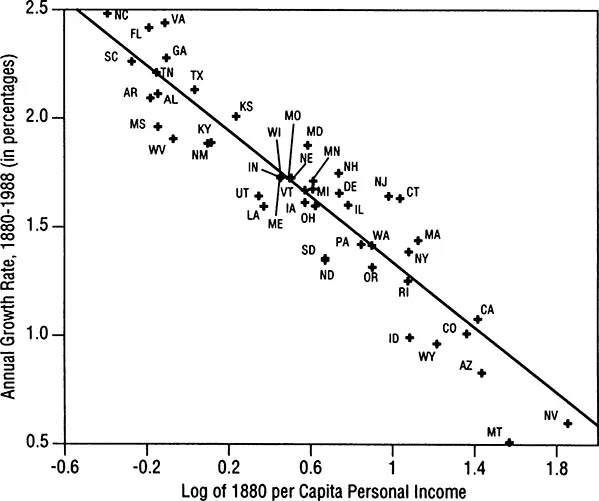

Figures 1.1 through 1.4 relate to regional economies, the U.S. states and the regions of some major countries in Western Europe. Figure 1.1, which applies to 47 continental U.S. states, plots the average annual growth rate of per capita personal income (exclusive of transfer payments) from 1880 to 1988 against the logarithm of per capita personal income in 1880. The figure shows a striking inverse relationship-that is, the places that were poorer in 1880 grew significantly faster in per capita terms over the subsequent 108 years. Thus, the behavior of growth rates across the U.S. states is consistent with convergence, in the sense of the poor places growing faster than the rich ones.

Part of the story that underlies Figure 1.1 is the catch-up of the southern states to the initially richer eastern and western states. But the convergence pattern applies equally well within regions as across regions; for example, the initially poor eastern states, such as Maine and Vermont, tended to grow faster than the initially rich eastern states, such as Massachusetts and New York.

Figure 1.1 Convergence of Personal Income across U.S. States: 1880 Income and Income Growth from 1880 to 1988.

Note: Data for Oklahoma are unavailable because 1880 preceded the Oklahoma land rush.

The data shown in Figure 1.1 effectively imply that the rate of convergence is roughly 2% per year (see Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1991, for the details). In other words, about 2% of the gap between a rich and a poor economy tends to be eliminated in one year. This rate of convergence implies a half-life of about 35 years; that is, it takes 35 years on average for half of an initial spread to vanish. Furthermore, it takes 70 and 115 years, respectively, to eliminate three-quarters and 90% of the gap. These numbers accord with the period of roughly a century after 1880 that it took for the per capita income of the typical southern state to come close to that in the typical northern state.

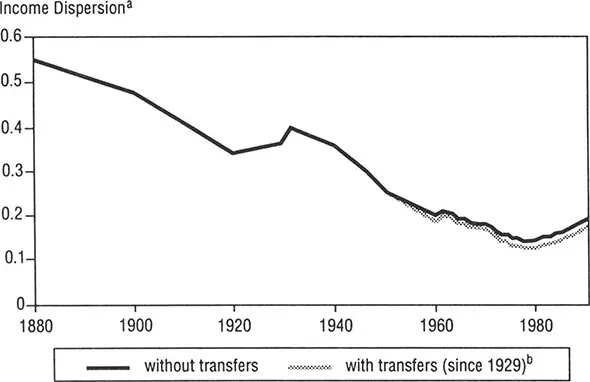

Figure 1.2 shows a measure of the dispersion of per capita income (the standard deviation of the logarithm of per capita personal income) across the U.S. states from 1880 to 1988. (Personal income is measured exclusive of transfer payments until 1929 and is shown with and without transfers thereafter.) The dispersion declined steadily from 1880 until 1920, then rose in the 1920s because of the sharp fall in real incomes originating in agriculture. The effect of the agricultural shock was pronounced because the agricultural states had lower-than-average levels of per capita income prior to the shock. The dispersion declined from the 1930s until the late 1970s, but increased during the 1980s back to the levels of the early 1960s.

Figure 1.2 Dispersion of Personal Income across U.S. States, 1880–1988

aIncome dispersion is measured by the unweighted cross-sectional standard deviation of the log of per capita personal income.

bData on the dispersion of per capita personal income inclusive of government transfer payments are included since 1929, although the effect of including transfer payments is negligible before 1950.

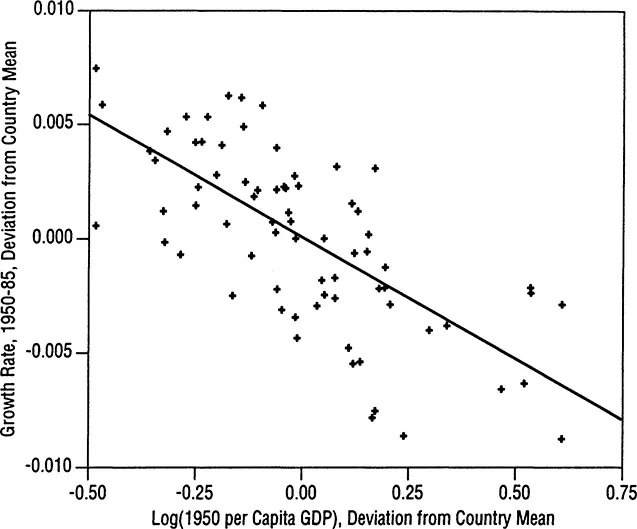

Figure 1.3 Growth Rate versus Initial Level of per Capita GDP for 73 European Regions

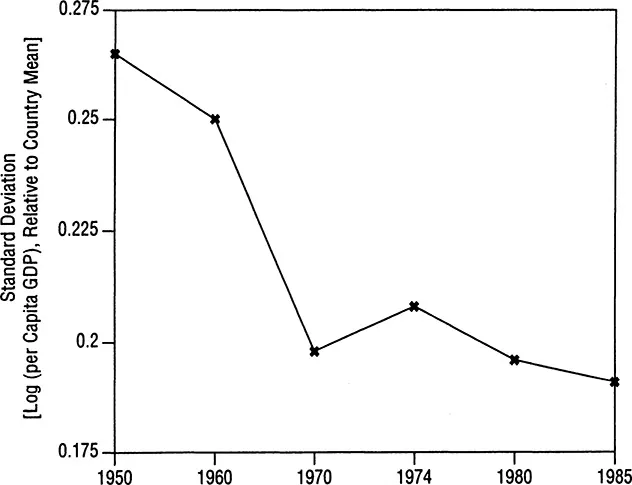

Figure 1.4 Dispersion of per Capita GDP across 63 Regions of Four Major European Countries

In the early 1980s, the rise in dispersion reflected the oil shock of 1979–80, an effect that was pronounced because the oil states already had above-average levels of per capita income. The behavior of oil prices does not seem, however, to account for the continuing rise in dispersion in the late 1980s. This recent behavior resembles the pattern for measures of inequality for the incomes of individuals and families. The rise in dispersion at the state level may therefore reflect elements that have been cited in studies of the increased income inequality for families: the changing technological mix and the increased returns to education.

Figures 1.3 and 1.4 describe the behavior of per capita gross domestic product (GOP) from 1950 to 1985 for 73 regi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- The Milken Institute for Job and Capital Formation: An Introduction

- PART ONE Capital Markets, Capital Formation, Savings, and Economic Growth

- PART TWO Financial Markets and Economic Regulation

- PART THREE Monetary and Fiscal Policy

- PART FOUR Government Spending and Taxation

- PART FIVE Concluding Thoughts

- About the Book

- About the Contributors

- Conference Participants

- Index