The Aim of This Book

This book analyzes and reconsiders the march to capitalism in Russia and in three important former Soviet-occupied countries, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic, during the recent post-Cold War period. It also examines the march in China, certainly a transition country, but unlikely to end in capitalism, as in the four European countries.

The literature on the transition economies, particularly that of Russia and the three Eastern restored democracies, is ample, responding to fast-moving developments.1 A close analogy to Russia’s transition literature would be that of the New Deal. The New Deal was similarly propelled by a cataclysmic event, replete with pain, suffering, and loss of status, strategized by youthful brain-trusters, marked by grand experiments and failures, great personalities and harsh demagoguery, and finally terminated by a process of muddling through. A residual question from the agony of America’s Depression is who saved capitalism? For Russia, the transition question may well be what kind of capitalism was saved?

Make no mistake about it: Russia has succeeded in lurching from socialism to capitalism. There is little if any chance it will revert to its seventy-year trajectory as the fear-inspiring, totally-centralized economy that worked well enough to challenge the Western profit system. Khrushchev’s threat to bury capitalism has vanished. Russia, the struggling survivor of the collapsed Soviet empire, has formally and substantively joined the opposition.

Reflections of a Distressed President

As 1996 ended, President Yeltsin, recovering from serious illness, could wonder when Russia would emerge from its chronic economic problems. He had barely won his re-election, but was still losing the economic war. Inflation continued, gross domestic product was less than that of 1991, his takeover year, crime and corruption were rampant, and his tax-collection system was in a shambles. The fruits of capitalism were bitter, with pensions unpaid, the state unable to meet its budgets, and the International Monetary Fund actually suspending Russia’s $340 million monthly payments, on funds already authorized, the penalty for non-compliance.

On the other hand, the distressed president could contemplate three remarkable signs on the economic horizon. First, from the calculating world of money and risk, a group of world-class investment bankers underwrote and easily sold $1 billion of Russian government bonds in the Eurobond market on November 23, the first public debt issue of a Russian government since the czars raised hundreds of millions on bond certificates destined to end as wallpaper.2 The Eurobond rate was a respectable 9¼%, with five-year maturity, compared with the 40% or more short-term rates being charged by Russia’s unruly commercial bankers, most of whom prefer to make high-rate loans to shady speculators, invest in embarrassingly high-yield government treasury bills, or buy into auctions and foreclosures of shares in privatized large corporations, rather than finance the thousands of creditworthy entrepreneurs unleashed by privatization. Five hundred of these rogue banks are reportedly marked for extinction by the harassed government, slow to learn the minimum rules of regulated capitalism, while still in awe of unfettered market capitalism.

Gazprom: A Transition Paradigm

The second economic triumph to savor was the initial public offering to foreign investors, in October 1996, of shares in Gazprom, Russia’s natural resources treasure and the world’s largest natural gas provider. Only a fractional 1.15% of Gazprom’s shares were offered. They netted $415 million and were oversubscribed fivefold. Foreign funds, whether from Eurobond sales or from selling to foreigners shares of state-owned property, are a high priority for cash-starved Russia, unable to pay on time its threadbare army, including 1,000 generals still hanging in. Above all, the funds are non-inflationary, going to the central bank, or in Gazprom’s case, the corporate entity, which owed at time of sale $2.8 billion in back taxes to the government, in turn desperately committed to reducing six straight years of very high, inflationary budget deficits.3

In addition, foreign investment, like foreign aid and favorable trade balances, offsets what the macrostabilization economists, who specialize in the total picture of national outflows and inflows, call capital flight. Capital flight in this case is nothing but the remittances of Russian wealth, preferably in dollars, sent by hasty and ingenious connivers to Swiss banks and other havens, under the quickly-learned market maxim of money first. The flight from 1992 to 1994 was well over $50 billion, from a high of $25 billion at the outset to about $10 billion in 1994. A top strategy of transition reformers in Russia at the start of 1992 was to declare the battered ruble freely convertible, a tough-minded tactic claimed necessary for engaging in the market world of open trade and finance, come what may. In a sense, it was a reversal of Roosevelt’s emergency post-inaugural bank-closing, the ban on further flight of gold bullion, and the end of time-honored currency convertibility into gold by citizens. But then America was on the gold standard, the banking system was at stake, and the country was paralyzed with fear. Passionate free-market ideology was also in disrepute.

Back to Gazprom, a classic paradigm for illustrating the complex issues surrounding Russia’s uneasy transition to capitalism. Historically it recalls the great natural resources, oil, gas, nickel, sometimes diamonds and gold, that sustained the old Soviet economic system. Selling such assets through the state export agency to the outside world for hard currency, or to puppet regimes for bartered goods, while the ruble was landlocked, enabled the government to subsidize the bread, energy, space exploration, nuclear arms, educational, cultural and sports organizations, and, in Western terms, a grossly inefficient economy. It allowed the closed society to become a belligerent superpower, at its demise in control of 400 million people. A group of intrepid politicians and economists, now within sight of an unprecedented, simultaneous turn to democracy and capitalism against great odds, deserves world sympathy, cooperation, and adequate financial aid to complete its mission.

There were no recognized budget deficits, as we account for them, in the former Soviet Russia, and apparently no unemployment. The great natural resources and hydroelectric projects loomed so large in world opinion that Gorbachev in his six-year period (1985-1991) borrowed or renewed about $60 billion from the world’s leading banks and friendly countries. The general secretary, later president, was apparently unconcerned with the debt burden of scheduled payments, only with repairing the cash-flow deficits. Since the Soviet Union, unlike Central and South American and other post-World War II borrowers, had never defaulted on interest or principal, it was a favorite of the international banks, who now have the distinction of their own club, the London Club of burned creditors. The unpaid governments belong to the Paris Club.4

Gazprom and the Stock Market

If a moderate number of shares brings close to a half-billion, non-inflationary, non-printing press dollars, why not phase in the rest of the shares on the oversubscribed foreign market for at least $50 billion more at the October 1996 sales price? Actually the world energy analysts figure that if Gazprom’s reserves were valued at Western prices, and then marked down for Russia’s political risk, the 100% market value would be at least in the $200 billion area, which is why the shares were snapped up. The successful underwriting represents a bet on Russia’s economic recovery and on the ultimate restructuring of its biggest industrial corporation into a rationally-managed profit center.

The shares represent ownership in the world’s largest natural gas producer. For all its inefficiency and old-style bureaucracy, its 1995 output was double that of the No. 2 producer, Royal Dutch-Shell Group, whose reserves are only one-thirtieth of Gazprom’s. Gazprom has 375,000 employees and sells 21 % of western Europe’s gas through an endless pipeline from Siberia, bringing in about $27 billion annually, much of it hard currency from foreign sales.

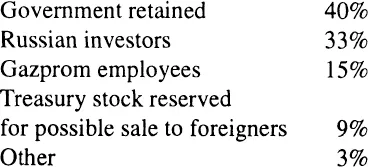

Gazprom’s privatization took place in mid-1994, towards the end of the great spin-off of state-owned enterprises that many believe pushed Russia permanently into the market system, regardless of continual political turmoil, sharply reduced gross domestic product and industrial production, and a majority of impoverished but vote-entitled citizens. These voters, incidentally, show up at the polls in far greater proportion than the increasingly disinterested electorates in the aging democracies. As a politically sensitive industrial dinosaur run by thousands of entrenched beneficiaries, Gazprom’s newly-incorporated 23 billion shares were allocated for distribution by the privatization bureau as follows:

Note that 40% is still owned by the government, hardly meriting the title privatization in capitalist terms. It is still a quasi-state enterprise, apparently enjoying tax exemptions, or at least decades of tax-paying defiance, as an instrument of state policy. Russia has had its full of outside advisors, but a hypothetical question can be raised. Why not reduce government stock to 20% (the typical effective-control percentage in capitalist countries) and phase out 28%, including the remaining 8% foreign sale allotment, to the ready-for-bailout foreign investors, netting another $14 billion from this fortuitous asset? It would enable the government to pay pensions and other arrearages, rehabilitate and reduce its bloated 1.7 million army, always a political threat in times of economic trouble, and see light at the end of the tunnel. Nothing works so easily in Russia. Aside from the fact that the hard-nosed investment bankers would resist flooding the market with more shares than stipulated as reserved for foreigners, there are negative aspects of Gazprom as a capitalist enterprise.

Here the author can avoid charges that he is promoting Gazprom shares. It has yet to issue an audited financial statement, not needed in a command economy, so its profit or loss is still conjectural, although gross income is believed to be $27 billion, as noted. It needs at least $15 billion over the next decade for repairs and improvements, according to the bankers. We have noted it owed the government about $3 billion in delinquent taxes at the end of 1996, and the government is now serious about tax collection and revising its irrational tax code. Moreover, having entered the competitive capitalist market, subject to profit and loss restraints, and with no subsidies or captive customers, Gazprom must compete with Norway’s Statoil, the second largest natural gas source for Western Europe, which announced in January 1997 a $14 billion contract over 25 years with Italian utilities. Norway’s business plan is to double European sales by 1998. The irony of this role-reversal should not be lost on international energy executives, flying over targeted markets in nationalized airlines for the most part. Norway, still regarded as being in the capitalist camp, although consorting with socialism, is the 100% owner of Statoil. The point is not to condemn Russia’s headlong plunge, but to keep in mind the ambiguities of an ideological rather than pragmatic attachment to market capitalism.

Interenterprise Arrearages

Returning to its role as a prototype for Russia’s economic travails, Gazprom owed approximately $8 billion in “interenterprise payments,” long overdue, in addition to its mammoth tax liability. For observers of transition economies, such payments represent a new category of economic dysfunction. The striking miners reported in the press, as many as 400,000 mainly in the Siberian regions at the end of 1996, are a good example. The coal operators, mostly private at this time, assert they cannot collect from their customers, the utilities, who in turn claim they cannot collect from the frazzled consumers, who feel energy should be plentiful and subsidized, as in the old days, especially in the cold Russian winters. This explanation is no doubt oversimplified for a highly complex issue unique to post-Cold War transition economies. Still the national total of arrearages, including unpaid military and state employee payrolls, as well as the interenterprise payments, is enormous, in the high double-digit billions, causing immense political and social unrest, as it should. Gazprom alone claims about $8 billion due from its utilities, as well as from defense industries and Russian Federation republics, who probably never intended to pay to start with.5

This absurd condition makes one speculate on the oft-proposed theory that Russian man, conditioned by generations of autocracy and collectivism before and during Communism, is not a candidate for “economic man,” motivated by individual striving and the desire for gain to participate in an efficiency-driven market-system.6 1 do not give credence to this theory, believing that modern man, in a technological world of mass production and highly-promoted markets, will instinctively adjust his life to efficiency as a matter of necessity and common sense. What cannot be helped is the inertia, or vacuum, produced by seventy years of a command economy, without some gradual transition to new institutions, such as credit devices, inventory control, and enforceable contracts. Above all, Russia needs such capitalist standbys as bankruptcy for failed or redundant firms, employee layoffs and relocation, unemployment insurance and reemployment training, all devices that would alleviate, in this instance, the accumulation of interenterprise and other arrearages. If you are going to have a market economy, why not adopt its built-in safety-valves and cushions? Perhaps it was impossible to do this under the pressure of circumstances, but the thought persists, six years later.