- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to a Theory of Political Power in International Relations

About this book

This title was first published in 2000: An in-depth look at the definition of power. The writing is well crafted and very readable and comprises a range of theoretical deliberations and analysis of the numerous aspects of political power and its use in international relations. This includes an examination of idea and structure: population; territory; economics; military; the political system; ideology; and morale and its forms appearing in international relations in the past, present and future: influence and force. This, coupled with the author's gift for teasing out the pertinent points in an argument and using relevant and interesting examples, provides an excellent piece of comprehensive insight into a theory of political power.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Political Power

1 Definition

Inequality is an objective fact that arises during the creation of social power by individuals, groups of people or organizations. Social power is a pre-requisite for the generation of political relations and phenomena, including political power. In certain instances, the organization and subjective guidance of social life and development under unequal social conditions are carried out through political processes, which are the substance of political power.

A social status quo thus becomes a political status quo. It is comprised primarily of power, force, violence, domination and other forms of rule within and over a society, and which are rooted in the need to remove the dangers or possible threats arising from the objective inequality of people, societies, states and other human organizations. A political status quo is established, maintained and altered primarily by political means and is both relative and dynamic: the more powerful, who benefit from the inequality, and the less powerful, to whose detriment the inequality is established, may quickly become less or more powerful, even trade places. Galtung's structural theory of imperialism 'takes as its point of departure two of the most glaring fact about this world: the tremendous inequality, within and between nations, in almost all aspects of human living conditions, including the power to decide over those living conditions; and the resistance of this inequality to change' (1980: 437).

Undoubtedly, political government is one of the basic expressions of political power, but the two phenomena cannot be equated: political power can exist without political government, although this power may to a great extent be identified with social power. However, government is impossible without adequate power - proof of it is that there are only a few exceptions of people not wielding the greatest power holding ruling posts. Also, government can be defined as the possibility of imposing one's will by organized use of force, and, in case of non-submission, by inflicting punishment.

Although political power is based on social power, it can sometimes be relatively independent of social power - at least temporarily, most often in revolutionary epochs – and need not be proportional to social power in all circumstances. In such instances, in order to maintain or change the status quo, power wielders (social or territorial groups, strata and, in exceptional cases, individuals) use accumulated social and political power potential for mutual attacks or defence (it is sometimes very difficult to distinguish between the two), coercion or overthrow attempts, which, again, can be differently perceived and evaluated.

Social power is in principle seen as an expression of the quest for progress and development in the broad sense of the word and the way to obtain it is to create it. The transformation of social into political power may result in very harmful consequences to man, above all, destruction, again in the broad sense of the word (Aron, 1962: 23). However, despite the internal controversy, different forms of power, particularly political power, have been an important goal to which people have aspired for millennia, sometimes at great sacrifice, in virtually all known social orders and systems.

The German philosopher and poet Friedrich Nietzsche (1844—1900) raised power to the pedestal of the topmost life value, identifying it with the very life of the individual and society (1972: 85). According to an American historian, politics is inseparable from power, and states and governments exist to wield political power. He said that there is always power throughout the world, be its balance stable, unstable or non-existent. Political power, he claimed, exists in the world and those who have it wield it (Becker, 1944: 83-4). Power obviously plays a central role in politics, and, consequently, in political science: politics itself is sometimes, indeed, in simplified terms, defined as a struggle for power and political sciences as the studies of power in human society.

Steven Lukes differentiates between three types of power. He considers, first, the 'pluralist' approach5 that provides 'a clear-cut paradigm for the behavioural study of decision making power by political actors, but it inevitably takes over the bias of the political system under observation and is blind to the ways in which its political agenda is controlled' (see 1977: 11, 15, 57).

Secondly, he offers a critique of the two-dimensional approach6 which 'points the way to examining that bias and control, but conceives of them too narrowly' because it lacks 'a sociological perspective within which to examine, not only decision-making and nondecision-making power, but also the various ways of suppressing latent conflicts within society'. According to Lukes, this approach includes 'a qualified critique of the behavioural focus of the first view ... and it allows for consideration of the ways in which decisions are prevented from being taken on potential issues over which there is an observable conflict of (subjective) interests, seen as embodied in express policy preferences and sub-political grievances' (1977: 20, 57).

Finally, Lukes's three-dimensional concept of power7 has the advantage of including a critique of the same focus of the two previous views 'as too individualistic' and allowing 'for consideration of the many ways in which potential issues are kept out of politics, whether through the operation of social forces and institutional practices or through individuals' decisions. This, moreover, can occur in the absence of actual, observable conflict, which may have been successfully averted - though there remains here an implicit reference to potential conflict.' It is not certain whether the above-mentioned potential, however, will ever be realized. 'What one may have here is a latent conflict, which consists in a contradiction between the interests of those exercising power and the real interests of those they exclude'. Lukes notes that 'the conflict is latent in the sense that it is assumed there would be a conflict of wants or preferences between those exercising power and those subject to it, where the latter become aware of their interests.' Those whose interests are excluded 'may not express or even be conscious of their interests, but ... the identification of those interests ultimately always rests on empirically supportable and refutable hypotheses' (1977: 24-5).

Lukes briefly concluded that it is possible to make a deeper, value-laden, theoretical and empirical analysis of power relations. A pessimistic attitude towards the possibility of such an analysis is unjustified. As Frey has written (1971: 1095), such pessimism amounts to saying: 'Why let things be difficult when, with just a little more effort, we can make them seem impossible?' (Lukes, 1977: 57).

In a later work, Lukes attempts to answer the question 'What interests us when we are interested in power?' and concludes that 'there are various answers, all deeply familiar, which respond to our interests in both the outcomes and the location of power.' This conclusion 'explains why, in our ordinary unreflective judgements and comparisons of power, we normally know what we mean and have little difficulty in understanding one another, yet every attempt at a single general answer to the question has failed and seems likely to fail' (1994: 17).

Finally, Lukes considers that it is likely that searching for a generally satisfying definition of power is in itself a mistake. He maintains that 'the variations in what interests us when we are interested in power run deep ... and what unites the various views of power is too thin and formal to provide a generally satisfying definition, applicable in all cases' (1994: 4).

Political power can be defined as the ability to rule, mainly implying the ability to impose one's will upon another, which is often but not always achieved through one's use of force, i.e. coercion, to achieve one's own goals and interests (see Stojanovic, 1982: 26-9). This ability contains two main components: an inner one - the rule within a certain state, i.e. society – and an outer one, which has a somewhat different form as it is manifested and administered in keeping with more or less specific rules governing international relations.

2 Basic Elements

Iron production was a crucial indicator of power in the mid-nineteenth century; in 1920 steel production took over. The number of horses was an important indicator of the quantum of an army's military force in the nineteenth century; after 1930, it was replaced by the number of tanks (Alexandroff, 1981: 79). The common denominator of wood, coal, petrol and gas is the fact that all are used as power sources; the common denominator of horses, tanks, planes, submarines and ships is that they transport arms, troops etc.

Similar comparisons can be drawn between the use of iron and steel and the subsequent discoveries often boasting better traits, broader applicability etc. Although classifications of political power elements still vary from one author to another, they mostly agree on the basic contours of the whole phenomenon. The above examples illustrate that certain specific segments of the structure of political and other forms of power have altered throughout history, although the so-called analogy of purposes is immediately apparent.

This classification of the common structure of political power comprises three basic elements of social power (population, territory, and economic potential) and elements specific to political power (military force, political system, ideology and morale). Although political power is in principle based on social power, it can act as an independent factor, more or less separate from social power. For instance, when individuals, groups, societies have political power but do not simultaneously boast correspondent social power, or, for example, when military power becomes independent, i.e. alienated from society, etc.

2.1 Population

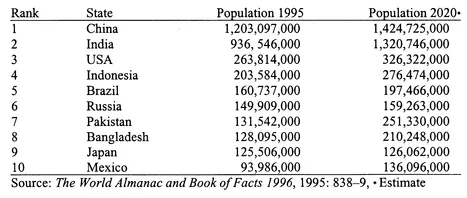

According to some criteria, out of the total of 5,734,000,000 people who made up the world population in 1995, over four-fifths of them lived in Third World states, and the rest in 28 developed countries. Table 2.1 lists the most populated states in the world.

Of the states listed in Table 2.1, the USA is considered a political superpower; Russia and China complete great powers while the rest are ranked below them. At the same time, only two states boasted a population of merely several thousand (see Cline, 1994: 37; PC Globe 5.0, 1992; and Kennedy, 1993: 21-46).

The English priest and economist Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834) claimed in his well-known theory that populations increase by geometrical progression, while the means of sustaining life (quantity of food, number of jobs, housing, etc.) grows by arithmetic progression. He therefore believed that the lowest social classes should refrain from marriage and procreation because, if they did not, population growth would result in revolutions, wars, epidemics and famine. Following up on Malthus's hypotheses, Nazli Choucri and Robert C. North arrived at the conclusion that a 1% increase in population called for a minimum 4% increase in social product in order to maintain the living standard at the existing level (see Choucri, 1972: 24).

Various authors find empirical confirmation of the theory that demographic pressure is the source of political disagreements and antagonisms arising when a state's territory is too small for its population and possibly causing outbreak of violence in societies, even the political disintegration of states in the history of India and some of its neighbouring countries. But they also find arguments to the contrary in the histories of Russia, China, The Netherlands and some other states. In all, past theories attached more attention to the effects of the demographic factor on politics in general and on political power than do contemporary ones.

The population's size is believed to have been much more important for a state's economic and military power potential when human muscles were the chief source of energy and production, and weapons just barely increased the physical strength of the workers and warriors. Since the Industrial Revolution, the importance of the population size has declined, while the significance of other factors, including the qualitative traits of populations (Dimitrijevic and Stojanovic, 1988: 99), particularly in developed industrialized countries, has grown. Hobbes had pointed out that the chief elements of man's 'natural power' were his strength, body fitness, wisdom and open-mindedness, together with other qualities (Enciklopedija politicke kulture, 1993: 685). Education, for instance, is an activity which obviously requires the spending of considerable economic and other resources, i.e. accumulated power, while its results subsequently constitute an extensive source of social and political power.

In order to determine the characteristics of political power elements in more detail, one may use data on public spending on health: availability of medical care; incidence of certain infectious and other diseases; number of children with low birth-weights; number of deliveries assisted by qualified staff, percentage of infants immunized against diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus or other diseases by the age of one, the mortality rate of women during delivery or from delivery-related causes etc. Also, when determining population traits, researchers use data on the availability of potable water, food, and personal and collective (usually family) hygiene facilities; data on whether there are larger minority groups which deviate from the average values of one or more of the above-mentioned indicators etc. (see Sivard et al., 1989, 1991, 1993).

A population's health and level of education as a rule indirectly affect other elements of political power. In many societies, state or quasi-state bodies are at least partly in charge of health and education as segments of the so-called social function of contemporary states; their administration is more or less regulated by exhaustive legal norms, laws, decrees, regulations, and other forms of state regulative activities.

Certain authors maintain that it is difficult to imagine a major power, particularly a superpower, without a sizeable population. However, as a state's population does not only create the GNP, but spends it as well, they also consider it an impeding factor. For these reasons, data on the population's age, ethnic, professional structures, health, life expectancy, sex, education level, territorial distribution, time needed to double the population, population growth, birth and death rates, infant mortality rate and other data should be borne in mind when deliberating on the demographic factor's importance for specific countries.

State territory if its characteristics do not serve to fulfil even the minimal needs and interests of its people. A state's economic power is most frequently the result of its population's work and creativity, and, in some cases, of the work done by the residents of other states. In numerous (in)direct ways, its people play a decisive role in the setting up, functioning and deciding on the use of a state's military forces. Some maintain that the ' size of the population is not per se sufficient to achieve adequate military power and therefore is not proportional to it' (Stojanovic, 1982: 61-2).

It would be difficult to imagine, even for merely theoretical purposes, state political systems without the people taking part in reaching and implementing political decisions varying in importance and scope and acting within political processes subjectively; people create and change the ruling system and other ideologies and their behaviour then conforms to or rebels against the status quo.

Finally, just as states are inconceivable without their populations, politics is inconceivable without the people shaping it, managing, implementing it and without the people it is applied to. The very ideas of social, political or other forms of power cannot be determined without, even if only implicitly, taking into account the fact that people (state residents) are the authors and wielders of power.

2.2 Territory

Some 71% of the Earth is covered by water, almost 9% of its surface by ice. The rest is entirely made up of state territories. In 1991 developed countries accounted for 36.22% and developing countries for 63.78% of the Earth's inhabited area. Territories of major powers accounted for a total of 27.15%.

The largest country in area was Russia, followed by Canada, China, USA, Brazil, Australia, India, the Argentine, Kazakhstan and Sudan. France ranks 48th and the UK 77th. The territories of Russia, Canada, China, USA, Brazil and Australia together comprise almost half the area of Earth inhabitable by humans. Monaco is the smallest state in the world (PC Globe 5.0, 1992; Cline, 1994: 36). Although possession of a large area is not in itself sufficient to make a state a major power, it is apparent that the first, third and fourth states boasting the largest territories are considered major powers.

Territory was an insignificant factor during the conception of politics and political power, but it subsequently gained in importance. For example, the borders of Ancient Greek city-states and those of the Roman Empire were not precisely determined; it was impossible to determine the precise borders of France even after the 1789 Revolution. This was the result of government organization and poor transportation, since these were the safest obstacles to quick incursions by potential conquerors into state territories. Nor did material production boast a volume enabling greater international trade so there was no need for state borders to protect the local market and producers from foreign competition. Major importance was, thus, not attached to state borders before industrial production and emergence of nations.

Since the advent of industrial production and nations, the belief has prevailed that the nation-states' borders should coincide as much as possible with the diffusion of ethnic groups. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, numerous attempts to fulfil these ambitions have resulted in clashes and wars, particularly in ethnically mixed areas, most often in border areas, due to attempts to cover up territorial pretensions by demands to establish ethnic borders. Secondly, it has also become desirable for a state's borders to include territorial and economic wholes, such as industrial basins, cities and their economic hinterlands.

Advocates of theories and ideologies that have for centuries striven towards development and change tended to minimize the importance of humankind's dependence on geographic and other factors in social relations. On the other hand, geopolitical proponents maintained that area bears the greatest relevance for the power of a state. German geographer Fridrich Ratzel (1844-1904) coined and used the term anthropogeography to denote a synthesis of geography, anthropology and politics. Ratzel said man, state and world are organic units, which take up a certain space as living organisms, grow, contract and die. He, however, concluded that they are not organisms in the true sense of the word, but 'aggregate organisms' whose unity is forged by moral and spiritual forces. He maintained that the extent of a state's territory determines the capacity of its power; therefore states want to seize as much territory as they can and are continuously fighting for living space (1899). This conclusion can be understood as a freer comparison of the major powers' battles to (re)distribute colonies in the author's time.

US admiral and historian Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) advocated a thesis concerning the special relevance of ruling the seas as a co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introductory Remarks

- PART I: POLITICAL POWER

- PART II: POWER IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- Bibliography

- Index

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Introduction to a Theory of Political Power in International Relations by Zlatko Isakovic in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.