![]()

Developmental dysgraphia: An overview and framework for research

Michael McCloskey and Brenda Rapp

ABSTRACT

Developmental deficits in the acquisition of writing skills (developmental dysgraphias) are common and have significant consequences, yet these deficits have received relatively little attention from researchers. We offer a framework for studying developmental dysgraphias (including both spelling and handwriting deficits), arguing that research should be grounded in theories describing normal cognitive writing mechanisms and the acquisition of these mechanisms. We survey the current state of knowledge concerning developmental dysgraphia, discussing potential proximal and distal causes. One conclusion emerging from this discussion is that developmental writing deficits are diverse in their manifestations and causes. We suggest an agenda for research on developmental dysgraphia, and suggest that pursuing this agenda may contribute not only to a better understanding of developmental writing impairment, but also to a better understanding of normal writing mechanisms and their acquisition. Finally, we provide a brief introduction to the subsequent articles in this special issue on developmental dysgraphia.

The ability to write is a fundamental component of literacy, and is crucial for success not only in school but also in most workplace environments. Unfortunately, a significant proportion of children suffer from developmental dysgraphia—that is, impairment in acquisition of writing skills. Döhla and Heim (2016) recently estimated that 7–15% of school-age children exhibit some form of development writing deficit.1

In addition to disrupting the acquisition of writing skills, developmental dysgraphia often has broader detrimental effects. For many dysgraphic children any writing assignment is an ordeal; the struggle to spell words correctly or produce legible handwriting is immensely frustrating, and also diverts attention from the more substantive aspects of the assignment (e.g., Berninger, 1999; S. Graham, Berninger, Abbott, Abbott, & Whitaker, 1997). A child struggling with spelling while writing a paragraph about frogs will probably learn less about paragraph composition, and about frogs, than a child with typical spelling skills; and a child who struggles to write digits legibly and align them neatly will probably work longer and harder at maths homework, while learning less, than a child with typical handwriting skill. Nor are the detrimental effects of developmental dysgraphia limited to children. Adults with significant developmental writing deficits may face limitations in career choice or advancement, as well as experiencing difficulty with everyday tasks that draw upon writing skills.

Despite the prevalence and significant impact of developmental dysgraphia, the topic has received relatively little attention from researchers. A major purpose of this special issue is to highlight the need for a strong, sustained programme of research. An intensified research effort is crucial not only for advancing our knowledge of the underlying deficits in children and adults with developmental dysgraphia, but also for improving diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, studies of developmental dysgraphia may enhance our understanding of normal cognitive writing skills and how these skills are acquired.

Writing and dysgraphia: Defining the scope

Writing and dysgraphia are both broad concepts, and the corresponding terms have been used in various ways. Hence, it is important at the outset to define the scope of our discussion and clarify our use of terminology. In discussing writing we focus on production of characters and individual words. Higher level writing skills, such as those involved in composing sentences and combining them into coherent texts, are beyond the scope of our discussion.

In other respects, however, we define the writing domain broadly. We include within our purview not only writing in print or script with a writing implement, but also other forms of written language production, such as typing on a laptop or texting on a smartphone. We also include both the ability to spell and the ability to plan and execute the motor processes required to generate an overt output. In the case of handwritten output we refer to the motor planning and production processes as handwriting processes, and include under this rubric both printing and cursive writing.

Turning now to writing impairments, the term dysgraphia has two different senses in the literature. Some researchers use the term to refer to impaired spelling, whereas others apply the label to deficits affecting the motor planning or production processes required for handwriting. We include both senses within the scope of our discussion. Finally, by developmental dysgraphia we mean impairment in acquisition of writing (spelling, handwriting, or both), despite adequate opportunity to learn, and absence of obvious neuropathology or gross sensory–motor dysfunction.

A theory-based approach

We advocate a strongly theory-based, as opposed to descriptive, approach to the study of cognitive deficits, including developmental dysgraphia. We argue that deficits affecting a cognitive function can be understood only by reference to a theory that specifies the normal cognitive representations and processes underlying the function (e.g., Caramazza, 1984; Caramazza & McCloskey, 1988; Castles & Coltheart, 1993; Hillis & Caramazza, 1992; McCloskey, 2001; McCloskey, Aliminosa, & Macaruso, 1991; McCloskey & Caramazza, 1988). Given such a theory, deficits can be characterized in terms of disruption to particular component(s) of the normal cognitive system.

Efforts to understand developmental deficits also require a theoretical framework specifying how the affected cognitive system is learned (Castles, Kohnen, Nickels, & Brock, 2014). Developmental deficits arise from disruption of normal learning processes. Consequently, a theory characterizing the learning processes is crucial for understanding the failures of learning that underlie developmental cognitive impairments. In the domain of writing, theories of learning are currently less well developed than theories of the normal adult system. Hence, we first describe a theoretical framework specifying the structure and functioning of the normal adult writing system, and illustrate the role of this framework in the study of acquired dysgraphia (writing deficits resulting from brain damage in adulthood). We then consider the processes involved in learning to write, and the potential roles of these processes in the genesis of developmental dysgraphias.

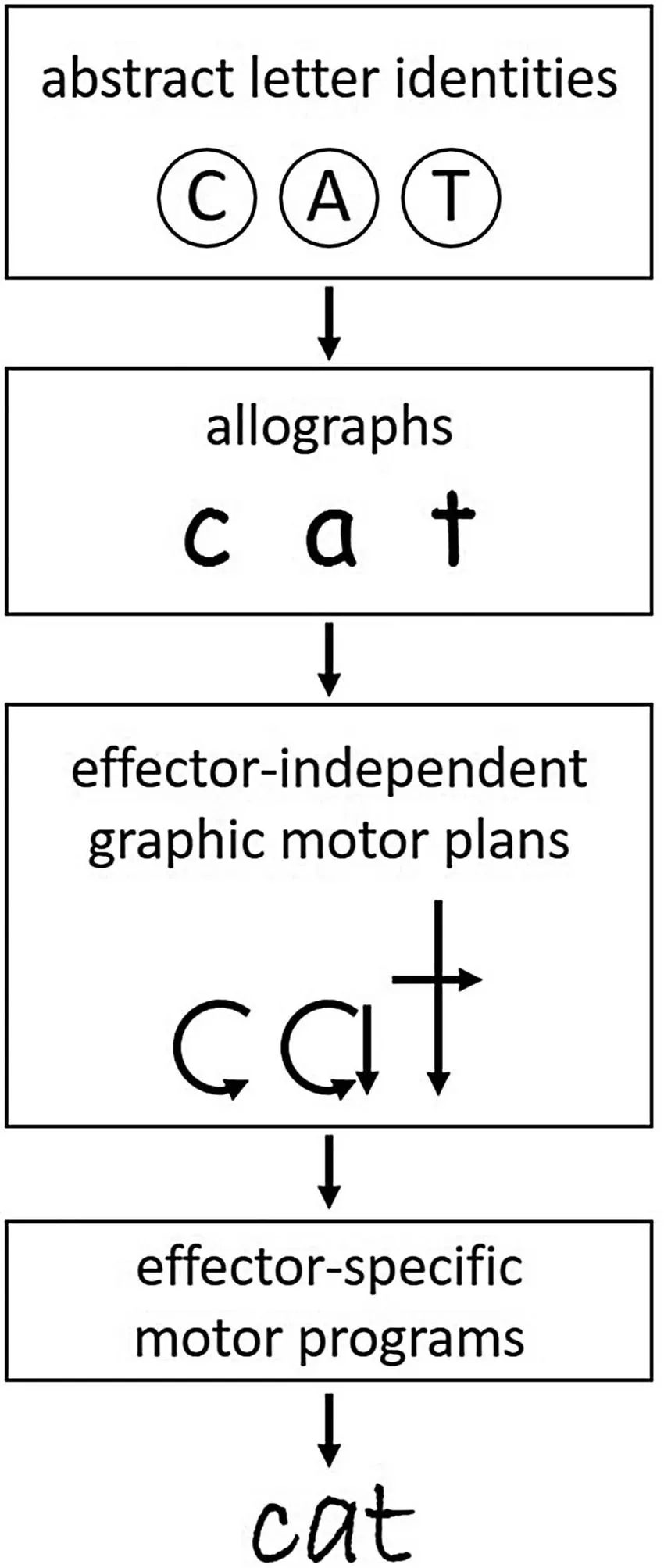

The normal adult writing system

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a theory of the cognitive mechanisms making up the normal adult writing system. Figure 1 focuses primarily on spelling mechanisms and Figure 2 on the mechanisms for the production of handwriting. The theory illustrated in the figures reflects a consensus (although not universal agreement) among scientists who study writing (e.g., Margolin, 1984; Miceli & Capasso, 2006; Tainturier & Rapp, 2001; see N. L. Graham, 2014, for a different framework). We offer the theory as a set of working assumptions that, while subject to revision in light of new evidence, can serve as a foundation for the study of developmental writing deficits. Note also that the theory assumes an alphabetic writing system. Although some aspects are applicable to non-alphabetic systems, other aspects would require extensive modification to address non-alphabetic writing.

Cognitive spelling mechanisms

Figure 1 illustrates cognitive spelling mechanisms in the context of a spelling-to-dictation task in which a word is dictated, and then is written or spelled aloud. The theory assumes that if the dictated stimulus is a familiar word (e.g., CAT), the sequence of phonemes computed by speech recognition processes (e.g., /k æ t/) activates a representation in phonological long-term memory (often referred to as the phonological lexicon), leading in turn to activation of a lexical–semantic representation. (Note that these auditory comprehension processes are not specific to spelling tasks.) The semantic representation in turn activates a stored spelling representation in orthographic long-term memory (also referred to as the orthographic lexicon). Some theorists have proposed that representations in orthographic long-term memory can also be activated directly from the phonological long-term memory (e.g., Margolin, 1984), or by a combination of inputs from phonological long-term memory and lexical semantics (e.g., Hillis & Caramazza, 1991).

Figure 1. Schematic depiction of the cognitive mechanisms making up the normal adult writing system.

Figure 2. Schematic depiction of the cognitive handwriting mechanisms, which map abstract letter identities onto motor programmes for production of written responses.

The activated orthographic representation specifies the identity and ordering of letters making up the spelling of the word. The letter representations are assumed to be abstract (Rapp & Caramazza, 1997), in the sense that they specify only letter identity and not any aspects of letter form (e.g., the visual shape of a letter, or the strokes for writing it). The abstract orthographic representations provide the basis for producing various forms of output, including writing, oral spelling, and typing. Once activated, the sequence of abstract letter representations is held temporarily in an orthographic working memory (often referred to as the graphemic buffer) while the motor planning and production processes required for generating an overt response are carried out.

Spelling of unfamiliar words or pseudowords (e.g., GRAT) also implicates abstract orthographic representations. However, in this case no lexical–phonological, semantic, or lexical–orthographic representations are available in the lexical system. Instead a plausible spelling is assembled from the input sequence of phonemes (e.g., /g r æ t/), through a sub-lexical spelling process that applies sound–spelling correspondence knowledge. As Treiman (2017) argues, the sublexical process may apply not only simple phoneme–grapheme conversion rules (e.g., /g/ → G), but also more sophisticated context-sensitive rules (e.g., /s/ → C when followed by E, I, or Y). For this reason we refer to the sublexical process as sound-to-spelling conversion process rather than using the more common label of phoneme–grapheme conversion.2

Outputs of the sublexical process have the same form as representations of familiar words retrieved from orthographic long-term memory: sequences of abstract letter representations. Like the retrieved representations, spellings generated by the sublexical process are held in orthographic working memory, and production of the overt response proceeds just as for familiar words.

The lexical route, which involves retrieval of a learned spelling for a word, is necessary because (at least for most languages) the correct spelling of a word is not fully predictable from its phonological form. Accordingly, correct spellings cannot reliably be generated through sound–spelling conversion. For example, there is no way to predict from the sounds of the words KEEP and LEAP that the vowel is realized by the letters EE in the former and EA in the latter. Rather the spellings must be memorized (i.e., stored in orthographic long-term memory). Interestingly, studies show that even for languages with highly predictable spellings (e.g., Spanish and Italian) word spellings are learned and stored in orthographic long-term memory (e.g., Cuetos & Labos, 2001; Miceli, Benvegnù, Capasso, & Caramazza, 1997).

The sublexical sound-to-spelling conversion process is needed to generate plausible spellings for words whose spellings have not been learned, including words that have been encountered only in spoken form, and entirely unfamiliar words. For these words, the lexical route cannot supply the correct spelling, forcing reliance on the sublexical route.

A point we have not yet addressed concerns the interaction between the lexical and sublexical routes. One possibility is that the lexical route is first activated, and the sublexical route comes into play only if no stored spelling representation is activated. Perhaps more likely is that the two routes operate in parallel, such that both routes produce an output for familiar words (e.g., Houghton & Zorzi, 2003; Jones, Folk, & Rapp, 2009; Rapp, Epstein, & Tainturier, 2002; Tainturier, Bosse, Roberts, Valdois, & Rapp, 2013). Under this account any difference between lexical- and sublexical-route outputs would be resolved in favour of the lexical route. For example, if for the word LEAP the lexical route generated the spelling LEAP, and the sublexical route p...