Capital Mobility and Distributional Conflict in Chile, South Korea, and Turkey

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Capital Mobility and Distributional Conflict in Chile, South Korea, and Turkey

About This Book

Why did many emerging countries pursue risky financial opening policies in a reckless manner, even after the painful example of the Latin American debt crisis? Unlike trade liberalization, which has mostly been beneficial in emerging countries, the removal of capital controls has led to boom-bust patterns in many countries. It is not simply driven by class or sectoral interests, nor is it just a result of ideational changes in policy-making circles, or international pressure. Gemici argues that to fully understand the motivation for these policies, we need to take into account distributional struggles prior to their enactment.

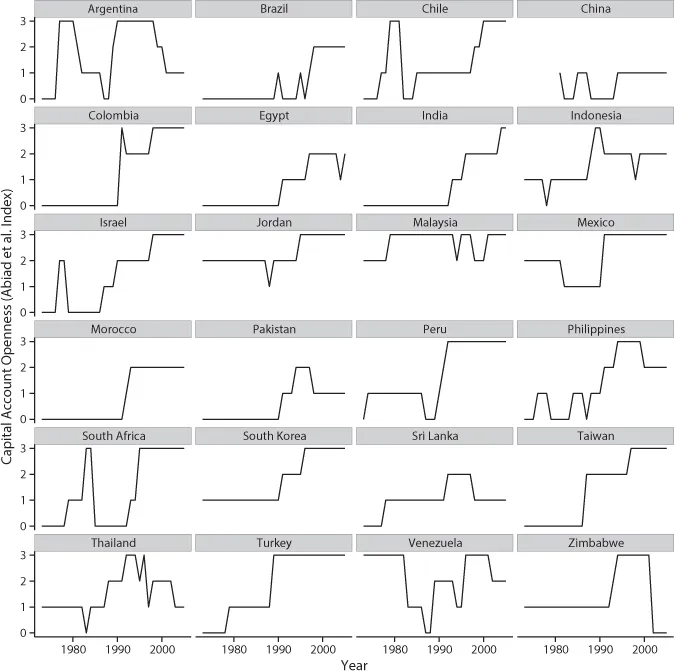

In this book, Gemici shows that conflictual distributional relations significantly increase the likelihood of capital account liberalization. Through in-depth comparative case studies, he also demonstrates that countries which liberalize in the most comprehensive manner tend to be the countries characterized by a high degree of distributional conflict. The case studies – Argentina, Chile, South Korea, and Turkey – have been chosen to maximise variation in distributional relations and to escape regional clustering, showing quite different trajectories of capital account liberalization.

This will be of great interest to readers in sociology, international political economy and heterodox economics, as well as specialists in the countries examined.

Frequently asked questions

Information

1 Introduction

Distribution relations and capital mobility

Which type of capital mobility?

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: distribution relations and capital mobility

- 2 Boom, crash, restraint: the politics of taming Capital flows in Chile

- 3 Embracing hot money, rejecting cold money in South Korea

- 4 Premature financial opening and boom-bust cycles in Turkey

- 5 Conclusion

- Appendix A: distribution and economic growth

- Appendix B: capital mobility and social interests

- Appendix C: perils of capital account liberalization

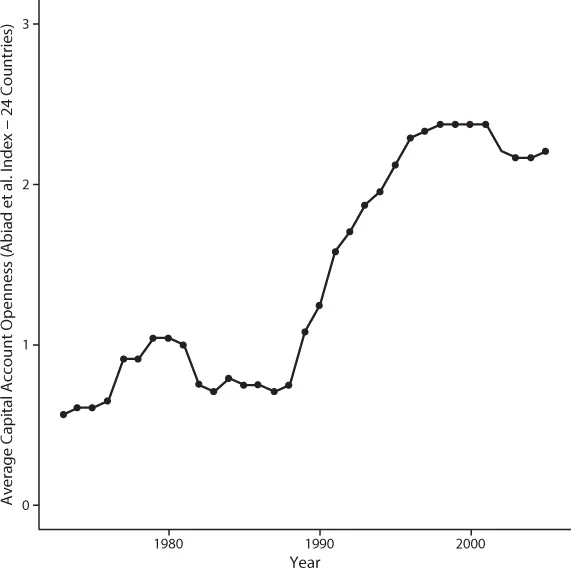

- Appendix D: measuring capital account openness

- Appendix E: list of interviewees

- Bibliography

- Index