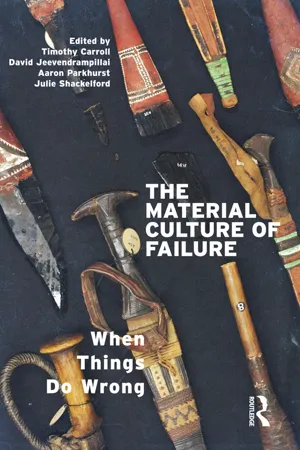

The Material Culture of Failure

When Things Do Wrong

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Material Culture of Failure

When Things Do Wrong

About This Book

What happens when objects behave unexpectedly or fail to do what they 'should'? Who defines failure? Is failure always bad? Rather than viewing concepts such as failure, incoherence or incompetence as antithetical to social life, this innovative new book examines the unexpected and surprising ways in which failure can lead to positive and creative results. Combining both theoretical and ethnographic approaches to failure, The Material Culture of Failure explores how failure manifests itself and operates in a variety of contexts. The editors present ten ethnographic encounters of failure – from areas as diverse as design, textiles, religion, beauty, and physical failure – covering Europe, North America, Asia, Africa, and the Arabian Gulf. Identifying common themes such as interpersonal, national and religious articulations of power and identity, the book shows some of the underlying assumptions that are revealed when materials fail, designs crumble, or things develop unexpectedly.The first anthropological study dedicated to theorizing failure, this innovative collection offers fresh insights based on the latest scholarship. Destined to stimulate a new area of research, the book makes a vital contribution to material culture studies and related social science theory.

Frequently asked questions

Information

1 Introduction: Towards a general theory of failure

Material failure and the materiality of failure

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Notes on contributors

- Foreword: Failure and fragility: Towards a material culture of the end of the world as we knew it

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: Towards a general theory of failure

- 2 Miracles and crushed dreams: Material disillusions in the design industry

- 3 When Krishna wore a kimono: Deity clothing as rupture and inefficacy

- 4 Whitened anxiety: Bottled identity in the Emirates

- 5 Holy water, healing and the sacredness of knowledge

- 6 Haredi (material) cultures of health at the 'hard to reach' margins of the state

- 7 Failure as constructive participation? Being stupid in the suburbs

- 8 Destruction of locality: On heritage and failure in 'crisis Syria'

- 9 Axis of incoherence: Engagement and failure between two material regimes of Christianity

- 10 The materiality of silence: Assembling the absence of sound and the memory of 9/11

- Afterword: Failure

- Index