This is a test

- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fashion and Masculinities in Popular Culture

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Popular culture in the latter half of the twentieth century precipitated a decisive change in style and body image. Postwar film, television, radio shows, pulp fiction and comics placed heroic types firmly within public consciousness. This book concentrates on these heroic male types as they have evolved from the postwar era and their relationship to fashion to the present day. As well as demonstrating the role of male icons in contemporary society, this book's originality also lies in showing the many gender slippages that these icons help to effect or expose. It is by exploring the somewhat inviolate types accorded to contemporary masculinity that we see the very fragility of a stable or rounded male identity.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Fashion and Masculinities in Popular Culture by Adam Geczy, Vicki Karaminas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Diseño & Diseño de moda. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Vampire Dandies

For the Western male image, and one that filtered to the rest of the world, the 1980s was very much that of the slim and fashion forward ‘New Man’ represented in the fashion style press; or, the muscle-clad, hypertrophied body of cinema’s he-men. The kind of musculature body made popular in cinema is not achievable to all body types and is potentially dangerous (injuries, steroid abuse). It is also not necessarily always desirable, and, in the end, is simply difficult to sustain, as the demands of life limit the many hours in the gym required for it. As a backlash and as an alternative, the ‘New Man’ emerged only a small time later, followed by the ‘New Lad’ and the metrosexual in the 1990s. The metrosexual was a yuppie with a particular accent on appearance and manner that was a kind of urbanised glamour. The explosion of male fragrances in the 1990s and the growing industry of male cosmetics proved congenial to the new male subject, one that appeared to take pleasure in beauty regimes desired by both men and women. The hypermasculine body that was so much part of the Reagan era was in many respects the somatic climax of the Cold War era, an era that conveniently divided the world into a simple binary structure: the Western Bloc, which included America and its allies, and the Eastern Bloc comprising of Russia and the communist states of Central and Eastern Europe. The fluctuating uncertainties of politics after the post-Perostroika era became noticeable on innumerable levels, including, male identities, which became a great deal more fluid and its orientations diverse. The representation of men was noticeably within a space that provoked both men and women to desire and consume the male image. The languid, svelte, brooding, and, above all, enigmatic male type to enter into the new millennium was a particular kind of dandy that had its roots in the nineteenth century decadent aesthete. His eschewal of nature over invention and contrivance also meant a special relationship to sexuality and death that had already been fermenting since the rise of Romanticism at the turn of the century. This love of the gothic emerged in decadent writing from about the 1850s until the end of the century, moving through salons, boudoirs, and private clubs embodying the world of corruption, intrigue, and decay that became associated with the English decadents, the aesthetes.1 The aesthetes aspired to set art and literature free from the materialist preoccupations of industrialised society. The metaphor of the vampire was a persistent theme in decadent writing and creative practice. The vampire and its accompanying behaviors and appearances were popular amongst the aesthetes of London and Paris.

In his poem Giaour (1813) Lord Byron writes of ‘the freshness of the face, the wetness of the lip with blood, are the never failing signs of a vampire’2. And then there was Byron’s medical practitioner, John Polidori, who wrote the novel Vampyre (1819). It is the story of a libertine, Lord Ruthven, modeled on Byron himself, who is an unscrupulous parasite who pursues, seduces, and kills women. Similarly, Bram Stoker’s classic horror novel Dracula (1897) was written to encapsulate this time of sexual ambiguity and anxiety present in Victorian society where conflicting discourses circulated about proper gender conduct (sexual and otherwise). The vampire embodied the ‘spirit of the times’, namely decadence, excess, artifice, beauty, and aestheticism. But glamour was always at a price: the fin de-siècle decadent maintained a rueful relationship to his delights, awaiting their imminent decay.

Historically the sexuality of dandies could often be ambiguous, and it is also true that men who secretly identified as homosexual would inhabit the dandy persona, there was a discernibly new bent to the character by the end of twentieth century.3 For the end of the millennium—together with impending ecological disaster and a myriad other interconnected pressures such as overpopulation and social division—had cultivated well-warranted global anxiety. In many ways the seemingly unquenchable public thirst for books, television series, and films with vampire themes and characters for the last twenty or so years is popular expression of such anxiety, as an expression of gloom but also as an antidote: the vampire lives on after the apocalypse. The dandy, the vampire, and the metrosexual are highly eroticised figures. All three figures embody alternatives to the common ways of living and acting and all three have an appetite for what is deemed perverse but which is also secretly desired. More than that, the vampire dandy that has its roots in fin-de-siècle literature can be seen to represent the new postmodern, posthuman body, as well as the conclusion of late capitalism itself, which has sapped the life from developing countries, and where the division between rich and poor continues to widen. Moreover, the age of so-called post-democracy, the end of faith in revolutionary change, the perceived indissolubility of capitalism, the doubtfulness of an alternative, all pointed to a circumstance of a death, but a death in which we somehow live on. But to take a dandified stance was to keep some vestigial defiance, and to assert, small as it might be, one’s place within the confused and unstructured contemporary continuum. This chapter focuses on the concept of the vampire dandy and its explicit/implicit relationship to the nineteenth century dandy, the vampire, and its twenty-first century incarnation, the metrosexual. These figures, or models of masculinity, in many similar ways interrogate conventional conceptions of masculinity and sexuality, appearing during times of political or economic crisis.

The Dandy

The dandy is what James Eli Adams calls an ‘icon of middle-class masculinity’, that emerged in England at the turn of the nineteenth century. The dandy wore clothes that were of a simple design with a clean cut and trim silhouette made of the finest fabrics. Thomas Carlyle described the dandy as

a Clothes-wearing Man, a Man whose trade, office, and existence consists of the wearing of Clothes. Every faculty of his soul, spirit, purse, and person is heroically consecrated to this one object, the wearing of clothes wisely and well: so that as others dress to live, he lives to dress.4

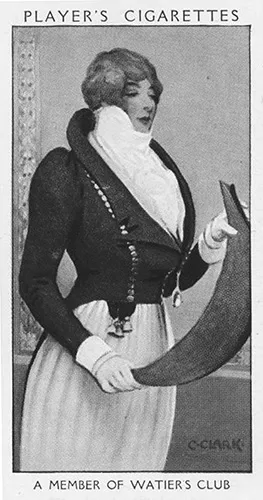

Yet there is no conclusive definition of the dandy. He occupies a space a contradiction, blurring the line between sexual orientation. He was neither heterosexual nor homosexual, but what today we might call queer. His sense of style hovered between exaggeration and discreetness (Figure 1.1). Sima Godfrey identifies this conflict as essential to the dandy’s character and entire state of being: ‘An eccentric outsider or member of an elite core, he defies social order at the same time that he embodies its ultimate standard in good taste’.5 Sobriety was a mark of ideal beauty that was characterised by perfectionism rather than ostentatious luxury. The dandy strove for calm and relaxed expression. Simultaneously he was a mixture of smouldering passions and sangfroid hidden depths masked by desuetude—what we might call the romantic epitome of cool. His beguiling presence was imbued with immense calm. As Charles Baudelaire emphasises, ‘The dandy is blasé, or pretends to be so, for reason of policy and caste’.6 At this juncture it is worthwhile to revisit the opening lines of Baudelaire’s essay on the dandy: ‘The rich, idle man, who is even blasé, has no other occupation than to follow the path of elegance’. He has ‘no other occupation than elegance’, and is always ‘distinct’ (à part). ‘Dandyism is a vague institution’ that is ‘beyond laws’.7 It is a compelling definition of the ‘everything and nothing’ sort. The dandy is the shadow of the conqueror of old, a shadow as he exists in world in which either everything is conquered or he is disable by his own aloofness and desuetude. In this, the dandy is the early modern exemplar of ‘cool’, wherein the exertion of too much effort is to betray a sense of need for what one does not have. To be cool is to be self-possessed and unencumbered by outside forces or stimuli. Hence as Baudelaire stipulates, dandyism’s own laws are beyond ‘excessive delight in clothes and material elegance’ and have more to do with cultivating an ‘aristocratic superiority of spirit’.8 Dandyism is an ‘unwritten’ caste of the ‘cult of self’ that has the measure of a ‘strange spiritualism’.9 It was a new modern religion of hypostatised but indeterminate subjectivity.

Figure 1.1 A Member of Water’s Club. George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library.

Baudelaire could not have written with such ebullience and conviction if it had not come from himself. The essay is in many ways a self-manifesto. As to his own appearance, Anita Brookner paints a vivid picture:

…as a young man he made determined efforts to outwit his dual heredity, the historical and the familial. He dressed with outlandish distinction: black broadcloth coat, very narrow black trousers, snowy white shirt, claret-coloured bow tie, white silk socks and patent leather shoes. He aspired to the form of distinction, emblem of a highly controlled mental and spiritual life, worn by that curious type of moral pilgrim and sartorial perfectionist whom he calls a dandy.10

His frequent impecunity prohibited him from maintaining such appearances, which he nonetheless sought through affecting defiance that reflected a new kind of aristocracy of the spirit of which art and poetry were the necessary off-shoots. The distinctiveness, separateness (à part) of the dandy is best exemplified by the first great dandy, George Bryan ‘Beau’ Brummell. At one stage a friend of the Prince Regent himself, Brummell was known entirely for himself and his appearance. He was neither an aristocrat nor an artist. He refined codes of fashion and appearance, stressing simplicity and cleanliness. Today Brummell is read retrospectively as a progenitor to the artists who made life their performance, such as Leigh Bowery or Andy Warhol, but he was also the result of the need of certain members of educated society to assert themselves on terms that were not those of the established nobility nor those of the careful (and middle brow) middle class. As Rosalind Williams observes, ‘in a society where the bourgeoisie loudly proclaimed the virtues of thrift, utility and work, the dandy rejected all these values as vulgar and sordid, and increasingly as irrelevant’.11 Brummel was the first great dandy, a precursor to celebrity culture and arguable the first public fashionista. He played an important role in the modernization of men’s clothing in which embellishment was jettisoned for fine tailoring. He objected to wearing pantaloons, which was the fashion of the times, preferring to wear trousers which soon became a staple of men’s fashion. His trousers were always tucked into his boots, giving his ensemble an equestrian look complete with tailored jacket and cravat. As we wrote in Queer Style, Brummel brought taste to the level of the person. ‘Taste was a common topic of concern for the upper classes of the eighteenth century in social manners and in the growing field of aesthetics’.12

Brummell had innumerable successors, documented and not, notably the Comte d’Orsay whose studied and extravagant appearance involved perfumed gloves, rings, furs, velvets, and silks placed together with little care for restraint. Barbey d’Aurevilly, Baudelaire’s contemporary, commented that the dandy ‘is always to come up with the unsuspected, what a mind accustomed to the yoke of rules cannot arrive at using regular logic’.13 It therefore unsurprising that the dandy became closely affiliated to the bohemian, who also wanted to flout the mores of the middle classes. There would continue to be a prevailing erotic dimension to the identity of the dandy.

Another important figure that straddled aristocracy, art, transgression, heroism, and outsider-dom was George Gordon, Lord By...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- 1 Vampire Dandies

- 2 Playboys

- 3 Hipsters

- 4 Sailors

- 5 Cowboys and Bushmen

- 6 Leather Men

- 7 Superheroes

- 8 Gangstas

- Conclusion: Men Without Qualities

- Bibliography

- Index