![]()

1 Wittgenstein and Merleau-Ponty on Gestalt Psychology1

Katherine J. Morris

Most famous for their researches on perception (and visual perception in particular), the Gestalt psychologists developed their theories, mainly in Germany, over roughly the same period as Husserl was developing phenomenology, and to some degree in dialogue with Husserl;2 this was also the period of Wittgenstein’s ‘early’ philosophy. Both Wittgenstein (in his ‘later’ period)3 and Merleau-Ponty (throughout his philosophical career) engaged directly with Gestalt psychology. Wittgenstein read rather little, although things that interested him for whatever reason he read in great depth. This category includes Köhler’s Gestalt Psychology (1947, hereafter GP),4 to which Wittgenstein came late in his career;5 he discussed Köhler extensively in his last lectures in 1947 (students’ notes on these lectures are published as Lectures on Philosophical Psychology 1946–7).6 Schulte goes so far as to say that GP ‘was the single most important influence on Wittgenstein during those years’ (1993: 76). Wittgenstein’s Köhler period was roughly contemporaneous with Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception. Merleau-Ponty was much more of a typical academic than Wittgenstein; he read widely in the psychology of his day, and he regularly characterised Gestalt psychology as ‘the new psychology’, as opposed to the empiricist and intellectualist psychology that had dominated previously.

Because Köhler is the main common denominator in their reading about Gestalt psychology, all of the references to Gestalt psychology in this essay will be to Köhler and most to the book Gestalt Psychology. I will focus on Wittgenstein’s and Merleau-Ponty’s critiques of Gestalt psychology’s descriptions of the perceived world.7 At first sight, Wittgenstein’s and Merleau-Ponty’s responses to these descriptions seem almost diametrically opposed. Wittgenstein was clearly intrigued by some of the phenomena to which the Gestalt psychologists drew attention but thought their descriptions of these phenomena confused. Merleau-Ponty, by apparent contrast, refers to the Gestalt psychologists as ‘the very psychologists who described the world as I did’ (PrP 23); his primary objection is Gestalt psychology’s failure to see the revolutionary consequences of its own discoveries. I will ultimately suggest that this appearance of diametrical opposition is misleading. Section 1 outlines GP’s descriptions of the perceived world. Sections 2 and 3 bring out Wittgenstein’s and Merleau-Ponty’s principal objections.8 Section 4 tries to bring Wittgenstein and Merleau-Ponty into dialogue with one another. The final section (5) reflects on this dialogue by way of drawing a few conclusions.

1. Gestalt Psychology’s Descriptions of the Perceived World

A great deal of GP is polemical, arguing against two strands of empiricist psychology, which then dominated the field: behaviourism (about which I can say no more in the present context) and what was known as introspectionism, whose basic premise is ‘the all-important distinction between sensations and perceptions, between the bare sensory material as such and the host of other ingredients with which this material has become imbued by processes of learning’ (GP 43). On this view, the sensation is ‘the genuine sensory fact’, by contrast with those ‘mere products of learning’ (GP 44). When we add to this move a bit of basic information about physics, optics, and the physiology of seeing, it can seem irresistible to assert that the ‘genuine sensory fact’ causally depends solely on the image on the retina, and that everything else we say we see isn’t strictly speaking seen, since it brings in further knowledge. Note, just for example, that this would imply that we cannot strictly speaking see depth (distance, three-dimensionality), since the image on the retina is two-dimensional.

Gestalt psychology’s conception of perception stands in sharp contrast to this. The most basic notion in Gestalt psychology is that of organisation, which, Köhler argues (GP 81), empiricism cannot accommodate.

This term ‘organisation’ points us in the direction of what the Gestalt psychologists call ‘circumscribed units’: ‘In most visual fields the contents of particular areas “belong together” as circumscribed units from which their surroundings are excluded’ (GP 80–1), for example, ‘things: a piece of paper, a pencil, an eraser, a cigarette, and so forth’ (GP 81).9 ‘Gestalten’ include both these segregated units and ‘groupings’ of such units: ‘a given unit may be segregated and yet at the same time belong to a larger unit’ (GP 84; cf. GP 95, 120). For instance, in Figure 1.1, each patch is itself a segregated unit, but the patches are also grouped into two groups of three patches each, as ‘everyone beholds’ (GP 83).

The groups consist of the three on the left and the three on the right, even though they could equally just be six patches, or the two groups consisting of the three on top and the three below, etc.

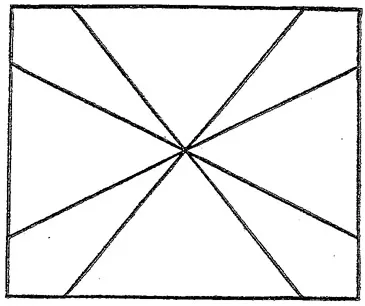

Of particular interest to Wittgenstein are what the Gestalt psychologists call ‘reversals’ in ambiguous figures (i.e., figures which spontaneously admit of different organisations). Consider Figure 1.2: whereas we might at first see ‘an object formed by three narrow sectors’, we may ‘suddenly see another pattern. Now the lines which belonged together as boundaries of a narrow sector are separated; they have become boundaries of large sectors. Clearly, the organisation of the pattern has changed’ (GP 100). Thus (pace the introspectionists) ‘[w]ith a constant pattern of [retinal] stimuli, we may see … two different shapes’ (GP 107).

Of especial importance to the phenomenologists are various characteristics of gestalten, especially those characteristics that contribute to the unity of the gestalt. According to the Gestalt psychologists, perceived objects maintain their apparent size, shape, colour, etc.—and hence their unity—through variations in distance, orientation, lighting, and so on. Hence they will speak of various ‘constancies’: ‘size constancy’, ‘shape constancy’, ‘colour constancy’, and so on. (Note that the introspectionists cannot allow such constancies, since, for example, the projection of a circular object such as a plate on the retina will vary in shape if the object is tilted.) Also important to the phenomenologists are such essential characteristics of gestalten as figure-ground structure (which, again, is impossible for the introspectionists to accommodate). A ‘circumscribed unit’ (the figure) is segregated from its surroundings (the ground), the figure having ‘the character of solidity or substantiality’, the ground being ‘loose or empty’ and ‘unshaped’ (GP 120). (Figure 1.2 above displays a figure-ground ambiguity: as long as we are seeing the cross with the slender arms, the area of the cross with the wider arms ‘is absorbed into the background, and its visual shape is non-existent’, (GP 107); in addition, ‘the oblique lines are the boundaries of the shapes which are seen at the time’, i.e., in this case they ‘belong to’ the slender cross, (GP 108, etc.) )

2. Wittgenstein’s Criticisms of Köhler’s Descriptions

Wittgenstein’s best-known discussion of the Gestalt psychologists’ descriptions occurs in his treatment of ‘aspect-seeing’ in PI II §xi.10 His initial focus is on ‘reversals’ of ambiguous figures; Wittgenstein reproduces a number of such figures, including most famously the ‘duck-rabbit’ (from Jastrow 1899), but also the ‘double cross’ (PI II 207), which is similar to Figure 1.2 above. Wittgenstein speaks of the different organisations of these figures as ‘aspects’ and of reversals as ‘changes of aspect’. What appears to strike Wittgenstein about reversals is a kind of paradox, which he expresses thus: ‘One would like to say: “Something has altered, and nothing has altered” ’ (RPP I §966).11 This ‘paradox’ is essential to a change of aspect.

W1. Two (or Three?) Uses of the Word ‘See’

Wittgenstein is as resistant as Köhler to the empiricist temptation to say we don’t (strictly speaking) see aspects: ‘if someone wanted to correct me and say I don’t really see [these things, but only shapes and colours], I should hold this to be a piece of stupidity’ (RPP I §1101).12 Wittgenstein’s central objection to Köhler is that he supposes that we see organisation in the same sense that we see colour and shape (cf., e.g., RPP I §1023). Not only does this involve a conflation, it means that Köhler can neither express nor dissolve the ‘paradox’.

Köhler’s view apparently implies that what one sees changes in a change of aspect in the same sense that what one sees would change were the colours and shapes to alter. (A change in organisation ‘amounts to an actual transformation of given sensory facts into others’ (GP 99).) Wittgenstein clearly takes there to be a powerful temptation to say this (RPP I §534, cf. RPP I §535, §536, §1107). However, to give in to this temptation is to leave oneself unable to recognise the paradox which is of the essence of aspect change: there is no sense, in this case, in which everything remains the same. Wittgenstein claims that to ‘put the “organisation” of a visual impression on a level with colours and shapes’ is to proceed ‘from the idea of the visual impression as an inner object’ (PI II 196); indeed this idea is commonly seen as the real target of these remarks.13 From this perspective, he imagines Köhler saying that the ‘outer picture’ (e.g., the drawing of the duck-rabbit) has remained the same while the ‘inner picture’ has changed. However, this would get him nowhere: one ought to be able to represent the ‘inner picture’ with a drawing (an ‘outer picture’), since the notion of an inner picture is modelled on that of an outer picture; but if one tried to represent what the duck-rabbit was like before the change of aspect and what it is like now simply by making an exact copy of what one sees in each case, ‘no change is shewn’ (PI II 196; cf. RPP I §1041; PI I §196).

Wittgenstein asserts that the phenomena of aspect-seeing and change of aspect point to ‘the difference of category between the two “objects” of sight’ (PI II 193). Here, the two ‘ “objects” of sight’ are not the ‘before’ and ‘after’ of an aspect-change as they were for Köhler; rather, they correspond to ‘[t]wo uses of the word “see” ’, which he exemplifies thus: ‘ “I see this” (and then a description, a drawing, a copy)’ as opposed to ‘I see a likeness between these two faces’ (PI II 193; cf. RPP I §964). How do these exemplars relate to changes of aspect? We have seen already that any attempt to represent the ‘before’ and ‘after’ in a change of aspect with a drawing or copy would show no difference; rather, one might (for example) convey the change by first grouping the drawing with a number of other drawings of ducks, and then with a number of drawings of rabbits (cf. PI II 196–7),14 and drawing attention to the likenesses in each case. Once we have distinguished these two uses of the word ‘see’, the apparent paradox vanishes: what you see in the first use of the word ‘see’ does not change, whereas what you see in the second use changes.

Importantly, the distinction, or at least some distinction, between different uses of the word ‘see’ has application beyond the rather special case of ambiguous pictures, even if other cases do not involve the ‘paradox’; since all perceived objects (not just pictures, much less just ambiguous pictures) are, according to the Gestalt psychologists, organised, many of the same issues arise for figure-ground organisation, three-dimensionality and so on. Wittgenstein clearly recognises this; thus RPP I §1023 reflects on Köhler’s commitment to the idea that ‘object’ (figure) and ‘ground’ are ‘visual concepts like red and round’ (cf. RPP I §1118: ‘Indeed, you may well say: what belongs to the description of what you see, of your visual impression, is not merely what the copy shews but also the claim, e.g., to see this “solid”, this other “as intervening space” ’). Wittgenstein suggests that if one were to ask what, in a drawing, ‘corresponded to the words “object-like” ’, the answer would be ‘the sequence, the order, in which we made the drawing’, which is surely not in the drawing in the sense that the colours and shapes are (RPP I §1023). Again, RPP I §85 considers the question of whether depth can ‘really be seen’; he goes on to suggest that the sense in which we see colour and shape and the sense in which we see depth are different senses, the one perhaps to be represented ‘using a transparency’, the other ‘by means of a gesture or profile’ (cf. also RPP I §86).

It is not entirely clear whether the sense in which we see depth, or see a thing ‘as a thing’ or as ‘object-like’, is the same as the sense in which we see aspects, thus it is not clear whether we should b...