![]()

My Dear Friend:

You remember the old fable of “The Man and the Lion,” where the lion complained that he should not be so misrepresented “when the lions wrote history.” I am glad the time has come when the “lions write history.” We have been left long enough to gather the character of slavery from the involuntary evidence of masters.

Letter from Wendell Phillips to Frederick Douglass, 1845

If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

Developing in the early nineteenth century, the school of “scientific racism” emerged as a racist response to scientific discoveries that were challenging long-held assumptions about essential human difference from animals. “Exploiting these discoveries of similarity” between human and nonhuman animals, scientific racism attempted “a reinscription of race along the line of species” (Boggs, “White Exceptionalism and the Animalized Slave”). Polygenists, for example, in addition to their argument for different racial origins, intimated that blacks were actually of a different species than whites, placing them in a category closer to animal than human. No one occupied this liminal position more overtly than the black slave, who was forced to oscillate constantly between the classifications of animality and humanity.

Within a literary context, the best “proof” of blacks’ lack of humanity was, quite simply, Africans’ illiteracy. We might assume, then, that slave narrators, in a desperate attempt to write themselves into the human community, professed their humanity via a literate display—in terms of both the fact of their literacy and the content of this literate display—of their difference from animals. Yet scientific racism ironically demonstrates how easily the privileging of “the human” can be used against humans, and quite obviously, against animals. So to what extent did slave narrators unquestioningly seek the status of the human? How radically did they call into question the humanist foundations of their enslavement? And how might the acquisition of literacy serve not simply as proof, but also as challenge, to assumptions of human exceptionalism?

Keeping the ideology of scientific racism in mind, I want to look briefly at the 1838 and 1848 editions of the slave narrative of Moses Roper before moving into Frederick Douglass’ 1845 slave narrative. William Andrews argues that, until the late 1830s, slave narratives tended to be more concerned with “the slavery of sin than with the sin of slavery” (5). By the end of the decade, however, the antislavery movement had traded in the role of reformer for crusader. This shift in emphasis from the sins brought about as a result of slavery to the inherent evil of slavery, in effect, marks a move away from a focus on slave welfare to slave abolition, resulting in the classic narratives of the 1840s (such as those not only of Douglass but also of William Wells Brown, James W.E. Pennington, and Henry Bibb).

But while Roper’s original narrative may indeed provide a template for these later narratives, it actually continues and even concretizes, in its 1848 edition, an ethic of welfare—one that seeks palliative rather than systemic change—in its challenges to slavery via the traditional, humanist proclamation of the slave’s exceptional humanity. Frederick Douglass’ narrative, however, at pivotal moments inverts this rhetoric of welfare, demonstrating how humanism is ultimately at work not in the resistance to slavery, but in its very production.

A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper from American Slavery (1838) contains some of the most prolific and graphic descriptions of slave punishment and torture within the genre: there is an excess of descriptions of how slavery puts the body in pain. Revolving around a seemingly endless cycle of attempted escapes and subsequent captures and punishments, these detailed accounts—including the removal of Roper’s fingernails by the pressure of a vice and the setting of his tar-drenched face and head on fire—far exceed the genre’s obligatory scenes of whippings (of which Roper describes around twenty of his own). Lingering over these many and excessive scenes of slave breaking, the narrative illustrates how crucial animal presence is in the making and maintenance of slavery.

Roper describes the slippery slope by which the slave, relegated to the position of chattel by his human master, can quickly be further degraded by becoming “mastered” by the animal, as he describes one punishment he suffers as a result of a failed escape:

This scene demonstrates both the shared yet unequal relations between slave and draft animal. Both are considered chattel personal, expected to labor for their master’s profit, but within this shared position the horse is clearly expected to work for and to be mastered by the slave. The collapse and explicit reversal of this hierarchy—the fungibility of slave and animal—makes this punishment, for Roper, so remarkable.

That Roper’s labor is divorced from agricultural productivity (“it was of no possible use to my master to make me drag [the barrow] to the field, and not through it”), and determined solely by his service to the horse, demonstrates that slavery is not only about the physical possession and exploitation of the human body’s labor, but about ontological production. What Roper describes as his degradation is designed to extract from his labor not cotton, but a reformed slave. What mediates and enables this production of the slave—the relation between Roper and his master—is the body of the horse.

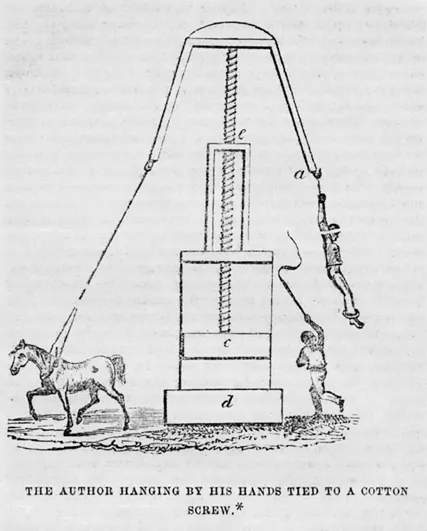

Roper goes on to provide a more elaborate example of punishment that expands on this previous one (Figure 1.1).

Mechanically, of course, the screw (e) transfers energy from one plane to another, typically functioning to produce a revolution around itself, with the energy created traveling down its length to press and package the cotton between c and d. This energy is reversed, however (as evidenced in the angle of Roper’s body as it centrifugally swings out from the press), in the cotton press’ metamorphosis into what Roper describes as “an instrument of torture” (56), with this redirection of energy up and out the length of the screw (yet again, as with the barrow) producing not cotton, but the slave. This is only the most immediate reversal—one of several in the image—that points to the question of slave ontology.

We might expect this torture merely to transform the human into the animal—to dehumanize, as the human body is placed, quite literally, in the position of the horse, into machinery designed specifically for the animal body. Yet alongside this traditional move to equate slave and animal (and thus “reduce” human to animal), the machine exists as an instrument of torture by using the (specifically) human form against itself, with Roper’s suspended and constrained body contributing to the gravitational pull that results in his pain. This pain is not so much dependent on the instrument’s insistence on the human occupation of the horse’s position as it is on its refusal to allow the human body to function as an equine body—to occupy that position fully. Importantly, then, such an apparatus depends on and underscores the difference of the human body while attempting to animalize that same body. The slave’s position demonstrates his taxonomical liminality under the ideology of scientific racism and slavery; not able to “fit” as either human or animal, the slave dangles from the machine, the “meaning” of his body unclear.

Abolitionist rhetoric attempts to rein in this multiple signification, securing the swaying body under its own ideology. Of course, the abolitionist presentation of slavery’s conflation of slave and animal was a common rhetorical tool, used to demonstrate slavery’s perversion of the Chain of Being, to show its insistence on contorted and “unnatural” ontologies. One of only two illustrations included in the first edition of the narrative, this diagram stresses that slave animality and liminality must, quite literally, be “manufactured” and are not innate, thereby turning slavery’s conflation of species into differentiation.

As the center of the abolitionist diagram, then, the screw (e) functions quite differently than it does as the center of slavery’s “instrument of torture” (as an inverted cotton press). It forms a line that bisects the illustration, so that the right side presents a typical “plantation scene” of the slave’s being hung up and whipped. On the left, the horse, harnessed to the press and functioning as a docile, draft animal, also presents a familiar scenario. When isolated, there is nothing “remarkable” about either one of these two vignettes.

While the reader might vehemently argue against the isolated whipping of the slave (not even considering it in reference to the horse in the left half of the diagram), the illustration’s full moral value under abolitionist ideology resides precisely in its argument for difference, its rebuttal to slavery’s “peculiar” congruence of these two opposing scenes; the proclamation of the humanity of the slave is made via and in contrast to the lack of humanity of the horse. The argument for abolitionism—articulated in the very machinery of slavery—proceeds mimetically.

But in a narrative that is so much about repeated and failed attempts at escape, to what extent does the narrative’s abolitionist logic “get away” from its own intent, from Roper himself? What are the perceived dangers, for abolitionism, in narratively replicating slavery’s abuses, and how does abolitionism attempt, yet again, to harness this signification to its own end?

The 1848 edition of Roper’s Narrative insists on a more blatant control of the original diagram’s excesses: two additional commentaries appear along with the diagram, both of which further revise the bodies in question (see Figure 1.2).

First, the caption, “The Author Hanging by His Hands Tied to a Cotton Screw*,” superimposes the authorial body onto the slave body. Second, the asterisk in the new caption refers to the possibility of the replacement of the horse with a human: “the screw is sometimes moved round by hand, when a person is hanging on it.”1 As in the barrow incident’s earlier reversal of human and animal labor, this asterisk points to the interchangeability of disciplined human and animal bodies: both can perform the required job. The footnote, then, actually necessitates the revised caption, as the diagram potentially collapses, again, at its previous site of difference.

The repeated struggle for control over the meaning of this illustration demonstrates abolitionism’s fear that the congruency of the diagram may be taken not as a proclamation of the slave’s humanity, but instead as a manifestation of his animality. The corrective to this is the attachment of the capacity for language to this animalized body, whereby the slave is irrefutably humanized as “author.” Implicit in this political attachment of authorship, however, is the denial of language in the horse. Either way, the animal (and the lack that the animal always implies) becomes a tool by which human status is denied or acknowledged. But what would happen if slavery’s insistence on fungibility were to be taken quite seriously—and productively—by a slave? How would the campaign against slavery be problematized and radicalized by a challenge to, not a reliance on, human exceptionalism?

In From Behind the Veil, Robert Stepto categorizes Frederick Douglass’ 1845 Narrative as “unquestionably our best portrait in Afro-American letters of the requisite act of assuming authorial control” (26). Focusing on the relation between appended documents that serve to frame and “authorize” antebellum slave narratives and the central, black-authored narratives themselves, Stepto argues that Douglass’ text distinguishes itself in that it “dominates the narrative because it alone authenticates the narrative” (17); as Stepto elaborates, “an author can go no further than Douglass did without himself writing all the texts constituting the narrative” (26). Wendell Phillips’ prefatory “Letter,” for example, the beginning lines of which comprise my first epigraph (and which I repeat below), contains passages directed at the reader “in need of a ‘visible’ authority’s guarantee” (19), but the letter is largely addressed to Douglass himself:

The epistolary form itself, Stepto asserts—the very act of correspondence between Phillips and Douglass—“implies a [unique] moral and linguistic parity between a white authenticator and black author” (19). This anomalous dialogue, however, does not exist independently, but is mediated. Simply addressed to “My Dear Friend,” the letter’s salutation does not make the identity of Phillips’ addressee immediately apparent; it is not, Stepto argues, until Phillips asserts, “I am glad the time has come when the ‘lions write history,’” that we are assured that he is indeed writing to Douglass. Phillips celebrates what he sees as Douglass’ accomplishment of authorship and the alternative history that it enables, but his introduction occurs through what we might assume to be a kind of dangerous side entrance: we are ushered into the slave narrative via the animal narrative (or fable); it is not only through the voice of the white male abolitionist, but also through the voice of the “lion,” that we transition into the voice of the slave author.

In some sense, then, the lion’s animal voice authenticates the slave narrator’s human voice. Of course, the collapse of lion into human serves as the origin of the fable itself and is the very implosion that allows for Phillips’ (lionized) reference to Douglass, functioning as a metaphor for all slave narrators, the biggest “lion” of all being Douglass himself (who later, in fact, adopted the nickname “The Lion of Anacostia”). Thus, the quotations around the phrase “lions [who] wrote history” in the first sentence of the epigraph frame the fictional lion’s “actual” words, but by the second sentence (the one which Stepto argues identifies Douglass) that same phrase has been appropriated in order to represent the slave narrator.

Nonetheless, Phillips speaks to Douglass by speaking for and through the animal; he illuminates Douglass’ success and the humanity it signifies by first shedding light (wholly anthropomorphic though it may be) on the lion. While Stepto’s assessment is so keenly attuned to intertextual dialogue, it fails to take account of the interspecies vocalization that enables this intertextuality. In introducing us to an example of history by and about a fugitive slave, Phillips asks (and answers, quite unsatisfyingly) the question of what a history by and about animals would look like. The analogy is clear: lions, like slaves (until recently), have not written their own history, and it is in this recording that misrepresentation may end; most basically, one must not only speak, but write for oneself—a feat that is now being accomplished by former and fugitive slaves. Phillips’ anthropomorphized lion struggles to gain entry, as did the slave, into the realm of (human) exceptionalism posited by Western philosophy—of autonomous agency and self-representation. This desire is made known through the lion’s voice, but the lion speaks just enough to articulate his deficiency: he can talk, but he can’t write; he has the desire to write history, but he can’t write history (or at least has not yet done so). In endowing the animal with the capacity to know literacy but the incapacity to attain it, the fable simultaneously blurs, as it solidifies, the classical borders of the human.

The fable of the misrepresentation of the lion’s history is, after all, itself a misrepresentation of the lion, begging the question, how can the history of animals be told/written/recorded without ultimately demanding their dismissal? And what are the material and rhetorical connections between slave and animal? Why, in the first place, even use the figure and voice of a (fictional) animal as a vector for the presentation of the figure and voice of a slave? Why would an abolitionist draw an analogy between these histories at the very moment when the slave is supposedly separating himself from the animal?

It would be easy to gloss over this animal reference as a tangent that Phillips, snugly secured within his white male humanity, can afford to make but that slave narrators surely couldn’t—or, at least, wouldn’t. But Douglass’ narrative follows up on these questions through a similar invocation of the animal that also marks a departure from Phillips’ fantasized lion. Dou...