![]()

PART I

Defining Food Security and Insecurity

![]()

CHAPTER 1 Definitions of Food Security

United States Department of Agriculture

1.1 RANGES OF FOOD SECURITY AND FOOD INSECURITY

In 2006, USDA introduced new language to describe ranges of severity of food insecurity. USDA made these changes in response to recommendations by an expert panel convened at USDA’s request by the Committee on National Statistics (CNSTAT) of the National Academies. Even though new labels were introduced, the methods used to assess households’ food security remained unchanged, so statistics for 2005 and later years are directly comparable with those for earlier years for the corresponding categories.

1.1.1 USDA’S Labels Describe Ranges of Food Security

1.1.1.1 Food Security

High food security (old label=Food security): no reported indications of food-access problems or limitations.

Marginal food security (old label=Food security): one or two reported indications—typically of anxiety over food sufficiency or shortage of food in the house. Little or no indication of changes in diets or food intake.

USDA government document. Available online at http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx.

1.1.1.2 Food Insecurity

Low food security (old label=Food insecurity without hunger): reports of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Little or no indication of reduced food intake.

Very low food security (old label=Food insecurity with hunger): Reports of multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.

1.2 CNSTAT REVIEW AND RECOMMENDATIONS

USDA requested the review by CNSTAT to ensure that the measurement methods USDA uses to assess households’ access—or lack of access—to adequate food and the language used to describe those conditions are conceptually and operationally sound and that they convey useful and relevant information to policy officials and the public. The panel convened by CNSTAT to conduct this study included economists, sociologists, nutritionists, statisticians, and other researchers. One of the central issues the CNSTAT panel addressed was whether the concepts and definitions underlying the measurement methods—especially the concept and definition of hunger and the relationship between hunger and food insecurity—were appropriate for the policy context in which food security statistics are used.

1.2.1 The CNSTAT Panel

Recommended that USDA continue to measure and monitor food insecurity regularly in a household survey.

Affirmed the appropriateness of the general methodology currently used to measure food insecurity.

Suggested several ways in which the methodology might be refined (contingent on confirmatory research). ERS has recently published Assessing Potential Technical Enhancements to the U.S. Household Food Security Measures and is continuing to conduct research on these issues.

The CNSTAT panel also recommended that USDA make a clear and explicit distinction between food insecurity and hunger.

Food insecurity—the condition assessed in the food security survey and represented in USDA food security reports—is a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food.

Hunger is an individual-level physiological condition that may result from food insecurity.

The word “hunger,” the panel stated in its final report, “...should refer to a potential consequence of food insecurity that, because of prolonged, involuntary lack of food, results in discomfort, illness, weakness, or pain that goes beyond the usual uneasy sensation.” To measure hunger in this sense would require collection of more detailed and extensive information on physiological experiences of individual household members than could be accomplished effectively in the context of the CPS. The panel recommended, therefore, that new methods be developed to measure hunger and that a national assessment of hunger be conducted using an appropriate survey of individuals rather than a survey of households.

The CNSTAT panel also recommended that USDA consider alternative labels to convey the severity of food insecurity without using the word “hunger,” since hunger is not adequately assessed in the food security survey. USDA concurred with this recommendation and, accordingly, introduced the new labels “low food security” and “very low food security” in 2006.

1.3 CHARACTERISTICS OF HOUSEHOLDS WITH VERY LOW FOOD SECURITY

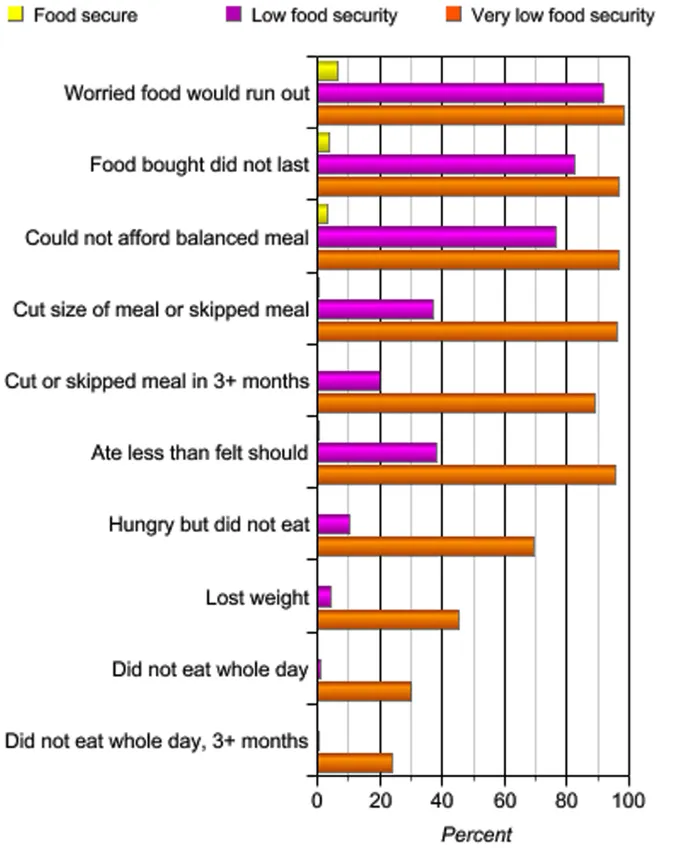

Conditions reported by households with very low food security are compared with those reported by food-secure households and by households with low (but not very low) food security in the following graph:

The defining characteristic of very low food security is that, at times during the year, the food intake of household members is reduced and their normal eating patterns are disrupted because the household lacks money and other resources for food. Very low food security can be characterized in terms of the conditions that households in this category typically report in the annual food security survey.

98 percent reported having worried that their food would run out before they got money to buy more.

97 percent reported that the food they bought just did not last, and they did not have money to get more.

97 percent reported that they could not afford to eat balanced meals.

96 percent reported that an adult had cut the size of meals or skipped meals because there was not enough money for food.

89 percent reported that this had occurred in 3 or more months.

96 percent of respondents reported that they had eaten less than they felt they should because there was not enough money for food.

69 percent of respondents reported that they had been hungry but did not eat because they could not afford enough food.

45 percent of respondents reported having lost weight because they did not have enough money for food.

30 percent reported that an adult did not eat for a whole day because there was not enough money for food.

24 percent reported that this had occurred in 3 or more months.

All households without children that were classified as having very low food security reported at least six of these conditions, and 69 percent reported seven or more. Food-insecure conditions in households with children followed a similar pattern.

1.4 GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY

ERS provides quantitative and qualitative research and analysis on food security issues in developing countries, focusing on food security measurement and the key factors affecting food production and household access.

The annual ERS International Food Security Assessment is the only report to provide a 10-year projection of food security indicators in 76 low- and middle-income countries.

In recent years, the ERS International Food Security Assessments have estimated that between 500 and 700 million people in the 76 countries studied are food insecure. The estimate for 2015 is 475 million food-insecure people (food-insecure people are those consuming less than the nutritional target of about 2,100 calories per day). However, food security conditions vary from year to year because of changes in local food production and the financial capacity of countries to purchase food in global markets. Despite progress, Sub-Saharan Africa continues to account for the bulk of the food-insecure people in the countries assessed, followed by Asia and then Latin America and the Caribbean.

1.5 GLOSSARY

A distribution gap measures the difference between projected food consumption and the amount of food needed to increase consumption in food-deficit income groups within individual countries to meet nutritional requirements. Inadequate economic access to food is the major cause of chronic undernutrition in developing countries and is related to the level of income. In the ERS global food security model, the total projected amount of available food is allocated among different income groups using income distribution data.

A nutrition gap is estimated to measure food insecurity. This gap represents the difference between projected food supplies and the food needed to support per capita nutritional standards at the national level.

A status quo gap is estimated to measure changes in food security. This gap represents the difference between projected food supplies and the food needed to maintain per capita consumption of the most recent 3-year period.

![]()

PART II

Food Insecurity and Mental Health

![]()

CHAPTER 2 Food Insecurity in Adults with Mood Disorders: Prevalence Estimates and Associations with Nutritional and Psychological Health

Karen M. Davidson and Bonnie J. Kaplan

2.1 BACKGROUND

Among health researchers, policy makers, practitioners, and decision makers, there are concerns about the growing global and ethical issue of food insecurity [1], defined as the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable food in socially acceptable ways [2]. The impact of food insecurity on mental health is significant and may be attributed to its associations with suboptimal diet [3, 4 and 5], and psychological issues such as depression, eating disorders, and impaired cognition [6, 7, 8 and 9]. Of the few investigations that have examined food insecurity in populations with confirmed diagnosis of a mental health condition, results have indicated an association with food insufficiency [10] and that patients in a psychiatric emergency unit who lacked food security had higher levels of psychologica...

FIGURE 1.1 Percentage of households reporting indicators of adult food insecurity, by food security status, 2014.Source: Calculated by ERS using data from the December 2014 Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement.

FIGURE 1.1 Percentage of households reporting indicators of adult food insecurity, by food security status, 2014.Source: Calculated by ERS using data from the December 2014 Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement.