eBook - ePub

National Traditions in Nineteenth-Century Opera, Volume II

Central and Eastern Europe

This is a test

- 530 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

National Traditions in Nineteenth-Century Opera, Volume II

Central and Eastern Europe

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume offers a cross-section of English-language scholarship on German and Slavonic operatic repertories of the "long nineteenth century, " giving particular emphasis to four areas: German opera in the first half of the nineteenth century; the works of Richard Wagner after 1848; Russian opera between Glinka and Rimsky-Korsakov; and the operas of Richard Strauss and Janácek. The essays reflect diverse methods, ranging from stylistic, philological, and historical approaches to those rooted in hermeneutics, critical theory, and post-modernist inquiry.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access National Traditions in Nineteenth-Century Opera, Volume II by Michael C. Tusa, Michael C. Tusa in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Opera Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

German Opera in the Early Nineteenth Century

[1]

THE ARIAS OF MARZELLINE: BEETHOVEN AS A COMPOSER OF OPERA*

If by “analysis” of a musical work we mean certain operations performed exclusively on the correct (we agree, of course, that “correct” texts exist of all the music we wish to analyze, be it Notre Dame organum, Cavalli operas, or Bruckner symphonies), final (since all composers proceed teleologically to compositional truth, we need only concern ourselves with “final” thoughts), printed (though we may cast an appreciative glance at the curve of Bach’s hand, surely we want abstract note values, not the slovenly appearance of a composer’s manuscript when we participate in such a serious undertaking) text (sanctioned if not by the composer himself at least by scholars who receive instructions from divine sources, via dove), if, I repeat, by “analysis” we mean certain operations performed exclusively on the correct, final, printed text of a musical work, one does not need a logician to demonstrate that sketches, by definition, are irrelevant to the process. So are history, chronology, performance practice, iconography, biography, and all other matters attendant on the holy icon. Whether we SHMRG with La Rue, graph with Schenker, label with Rameau, or explain with Meyer, truth lies at our fingertips, within the yellow covers of our friendly Eulenburg pocket score1.

For Marzelline’s aria, which opens Beethoven’s Leonore of 1805, we lack profound insights drawn by great “analysts”, since none has deigned to touch this particular strand of Beethovenian fluff. Embarrassed the master composed an aria at all for the love-sick jailer’s daughter, they would be further scandalized to learn he prepared no fewer than four complete versions of the composition and numerous layers of sketches. Had the high priests of linear reduction focussed their attention on Marzelline, they would undoubtedly have demonstrated the presence of an Urlinie, as well as an important ascending line which leads to a climax within the coda, to which we shall return. Rudolph Reti would gleefully have shown thematic interactions between the sections in minor and in major: triadic arpeggiation, conventional but nonetheless significant in unifying the piece. Leonard Meyer would have found a very real melodic gap, and filled it up. These and similar observations deserve elaboration, for they do indeed deepen our understanding of the composition.

But does our knowledge of the aria end there? Must we patronisingly label all other information “biography”, agreeing with Nottebohm2 that:

“… the sketches do not contribute to the understanding and actual enjoyment of a work. They are superfluous to the understanding of a work of art, certainly — but not to the understanding of the artist, if this is to be complete and comprehensive”.

Before such tyrannical absolutism we are sustained by the conviction that “understanding” and “enjoyment” of a work of art are extraordinarily complex matters, engaging us on many levels simultaneously. The study of a musical work is not a pyramid with one sacrosanct discipline, “analysis”, at the apex3. As musicians and scholars we strive for a more complete knowledge of each work of art. The various investigations undertaken by musicologists and theorists all contribute in various ways to this knowledge. Which details will ultimately lead to an individual’s increased understanding and enjoyment of a musical composition had best be left to that individual’s psychology.

Beethoven’s sketches have intrigued so many younger scholars because they are, fundamentally, musical documents. To be sure, they help us unravel complex problems of chronology; they make delightful intellectual puzzles for lovers of watermarks; they propel us from continent to continent on mad bibliographical dashes. But equally significant has been the surge of attempts to extract musical insight from the sketches. Not all studies have been effective, but, to take one example, our deepest knowledge of op. 131 is as profoundly touched by Robert Winter’s study of its sketches as by any analysis ever devised4. What is most remarkable is the number of different ways the sketches enlighten us about Beethoven’s music. Not every set can provide the same quality of information: sketches for middle-period symphonic works are different in magnitude from those for the keyboard sonatas. Nor must we presume that a pedestrian treatment of certain sketches exhausts their potential. With the formidable difficulty of transcription intensified by the even more complex need for comprehension, earlier scholars rarely confronted the task. Indeed, the bibliographical chaos of the sources almost precluded it. But only scholars of limited vision can fail to be awed before the possibilities these documents represent and even the preliminary musical insights they have already yielded5.

The Chronology of Marzelline’s Arias

Universal agreement can be found today that sketches, sensitively employed, help solve chronological problems. Those for Marzelline’s aria are exemplary. “O wär ich schon mit dir vereint”, the opening number in Leonore of 1805 and its 1806 revision, the second number in Fidelio of 1814, exists in four distinct versions: two predate the performance of 20 November 1805, one in C major, one in C minor/major (as in later versions); another was performed in 1805 (and again with trivial changes in 1806),of which a final revision, slight but significant, was made for Fidelio. No complete autograph survives for any of them. Their primary sources are in a collection of manuscripts pertaining to Beethoven’s opera, once belonging to Anton Schindler, grouped as Beethoven autograph 26, I in the Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz of West Berlin6. All have annotations in Beethoven’s hand. Willy Hess published the two early versions in his Supplemente to the very incomplete Beethoven edition. The 1805 version, with notes on the 1806 variants, appears in his edition of Leonore. When a modern critical edition of Fidelio is undertaken, the final version of Marzelline’s aria will depend largely on a manuscript in aut. 26, I: a copy of the aria as performed in 1806 with Beethoven’s autograph revisions of 18147.

It is widely assumed that the C major version was Beethoven’s original conception, followed by a second in C minor/major, leading in turn to 1805, after which the chronology is evident. Hess makes this assumption, so does Winton Dean in his lengthy study of Fidelio in The Beethoven Reader, so do most modern critics, ignoring the work of Nottebohm8. There are apparent reasons for believing in this chronology. Schindler, on the copy of the C major version in aut. 26, I, writes: “Diese Bearbeitung ist nach Beethovens Äußerung die allererste unter den vieren”9. Although Schindler is unreliable, even when not consciously falsifying documents, he has no obvious motive for misleading us here. Beethoven’s reputation in no way rests on which early version came first. And there is supporting musical evidence: if we yearn for an ostensibly coherent development, it is comforting to envision Beethoven beginning entirely in C major, then introducing the C minor/major polarity, and ultimately refining his ideas to achieve that perfection conveniently defined as the final version.

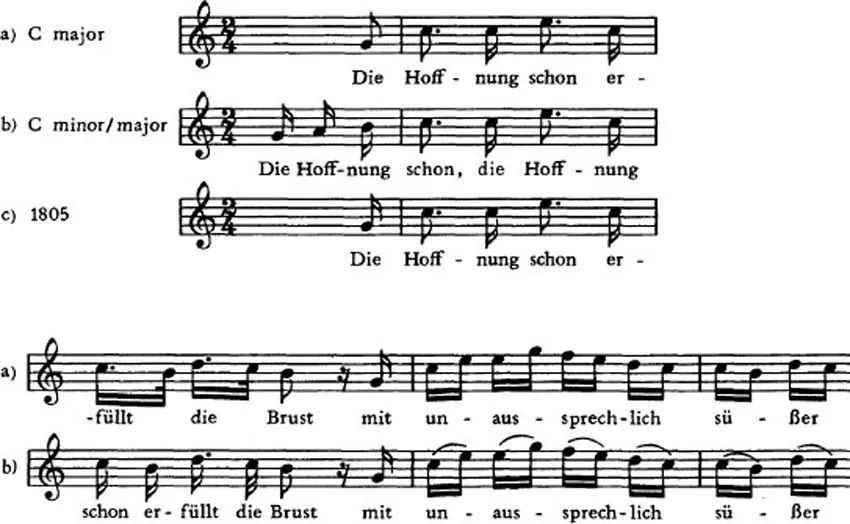

But there are excellent reasons for disputing Schindler’s statement. Example 1 presents the C major refrain common to both stanzas of this strophic aria, as found in 1805 and in the two earlier versions.

Example 1

Three versions of the C major portion of Marzelline’s ariaa

Three versions of the C major portion of Marzelline’s ariaa

The refrain of the C major version is intimately related to the refrain of 1805, whereas the refrain of the early C minor/major version stands somewhat apart. Of course the opening section of the latter, as we shall see, resembles 1805, whereas the opening section of the C major version is totally diverse. But in the two early versions these opening sections of each strophe are alternative settings of the text: one simply replaces the other. In the refrain, similar musical material pervades all three versions. That Beethoven would first compose the refrain of the C major version, shorten it significantly, altering many details, for the C minor/major version, and then revert to his original conception for 1805 seems unlikely — though not impossible. For if we are to be cautious about teleological models, we had best remain so even when we applaud their results. Still, on musical grounds, Schindler may well have been misinformed or confused about what Beethoven actually told him.

Sketches for Leonore principally appear in two books, Landsberg 6 and Mendelssohn 15. Studies by Rachel W. Wade and Alan Tyson, respectively, have assessed their bibliographical and paleographical problems10. Landsberg 6, the “Eroica sketchbook” contains the bulk of Beethoven”s work on that sympony11. Sketches for the first five numbers of Leonore, written early in 1804, occur near the conclusion of the book. Only those for No. 1 (Marzelline’s aria) and No. 2 (the Duet for Marzelline and Jaquino) are extensive. After a significant gap, perhaps an entire lost sketchbook, extensive. After a significant gap, perhaps an entire lost sketchbook, Mendelssohn 15 preserves Beethoven’s work from the second-act finale through Act III (recall that Leonore 1805, unlike Leonore 1806 and Fidelio, has three acts)12. It is a complicated source, with missing pages, added ones, and others out of order. Tyson’s reconstruction will be accepted here.

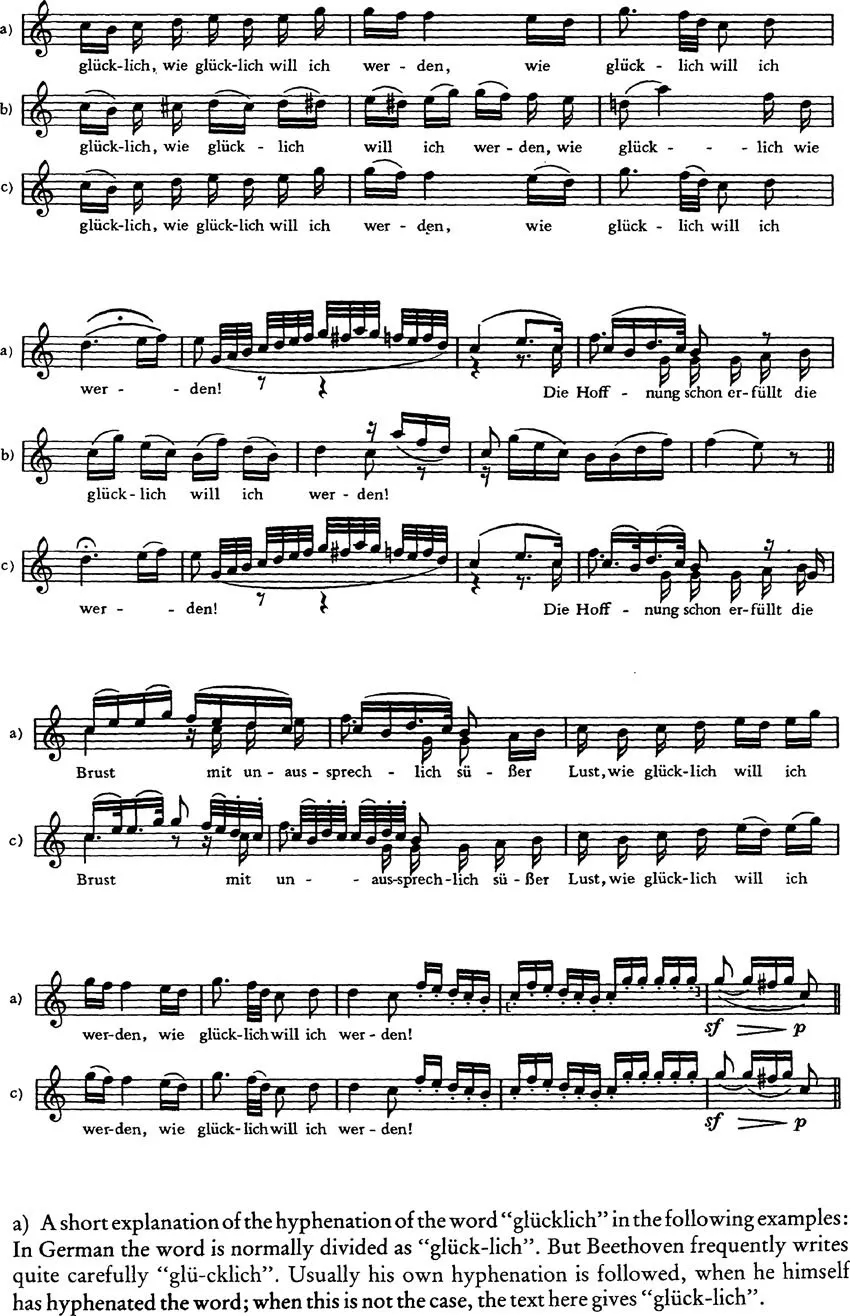

The first Leonore sketches in Landsberg 6 concern Marzelline’s aria, but Beethoven’s further active involvement with it continues throughout his composition of the opera. Example 2 presents an overview of these sketches.

Example 2

An overview of the sketches for Marzelline’s aria

An overview of the sketches for Marzelline’s aria

Stage 1: Sketches for the first version (C minor/major)

Source: Landsberg 6, pp. 146–155.

First continuity draft | p. 147/5–13 |

Associated fragments are found on p. 147/3–4 (?), 15, and 17–18, and also on p. 146/16–18. An additional fragment is found on p. 149/6–7. These fragments are mostly associated with the final measures of the C major refrain and with the concluding orchest...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- PART I GERMAN OPERA IN THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY

- PART II WAGNER

- PART III RUSSIAN OPERA

- PART IV STRAUSS AND JANÁČEK

- Name Index