J. Andrew Grant and Fredrik Söderbaum

Introduction

The study of regionalism and its many facets is enjoying a renaissance of sorts within the larger, overlapping context of international relations (IR) and international political economy (IPE). Obviously, the ‘region’ and its various incarnations is not a new concept. However, in the present era characterized by a certain measure of uncertainty regarding the effects of globalization on all forms of political, economic and socio-cultural identity, the region — whether intra-state or supra-state — is as salient as ever. Concomitantly, the current era is also characterized by an international system that is in flux. The perceived stability of bi-polarity during the Cold War gave way to a decade of uncertainty, as the so- called ‘New World Order’ of the post-Cold War era was anything but orderly. In turn, the post-Cold War era was punctuated by the terror attacks of 11 September 2001, leading some to conclude that we have now entered a ‘post-September 11th’ era accompanied by further approbation concerning the stability of the international system.

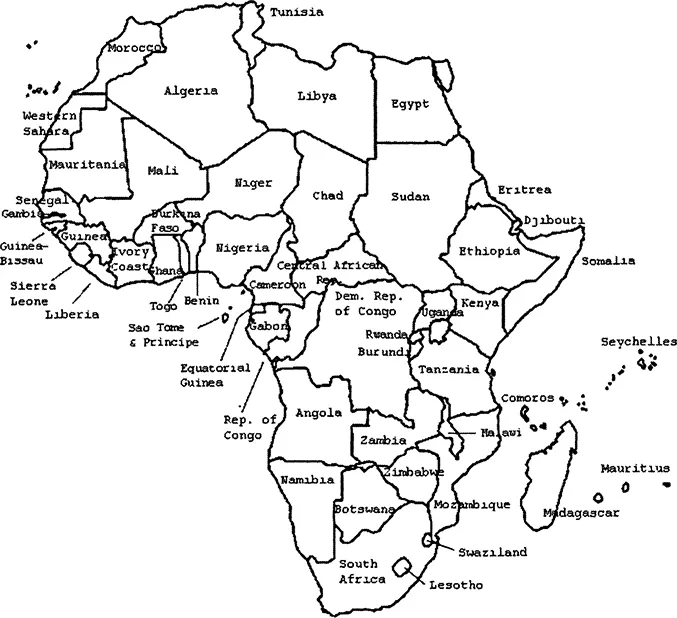

It seems appropriate therefore to recognize the need to transcend purely state-centric notions of not only the disciplines of IR and IPE, but of regionalism as well. This applies to all regions in all parts of the world, though the theoretical orthodoxy has tended to focus on formal and inter-state regional frameworks in Europe and more recently, in North America and Asia-Pacific. Africa is, to a large extent, neglected in the general debate on regionalism. Mainstream perspectives tend to claim that if there is any regionalism at all in Africa, it is primitive and characterized mainly by failed or weak regional organizations and a superficial degree of regional economic integration. While this is not altogether wrong, it obscures the fact that there are intense and multi-dimensional processes of regionalization in Africa. The African state-society nexus is based on multiple actors that are linked together in hybrid networks and coalitions, together creating a wide range of complex regionalization patterns on the continent. Indeed, as Dunn (2001: 3) correctly asserts, ‘African individuals and policy makers continue to construct creative and original responses to meet their political, economic, and social needs’.

Rooted in what is broadly defined as ‘the new regionalism/regionalisms approach’ (NRA), this edited volume transcends conventional state-centric and formalistic notions of regionalism and seeks to theorize, conceptualize and understand the multiplicities, complexities and contradictions of regionalization processes in contemporary Africa. It is in this vein that the collection not only unpacks and theorizes the African state-society complex with regard to new regionalism, but also explicitly integrates the often neglected discourse of human security and human development. In so doing, the book moves the discussion of new regionalism forward at the same time as it adds important insights to security and development as such.1

This introduction is structured in three main sections. The first rather comprehensive section describes the broad paradigm of the NRA, with emphasis on the transcendence of state-centric and formal regionalism, the core concepts such as regions, regionalism and regionalization, and finally the intriguing relationship between globalization and regionalization. In the second section, the human security and human development discourses are discussed in the context of how they fit with the NRA. The introduction concludes with an outline of the structure of the book and a presentation of the individual chapters.

The New Regionalism/Regionalisms Approach

Regionalism has returned as one of the leading buzz-words in international studies. The term ‘new regionalism’ has been widely employed in the ensuing theoretical, ontological and methodological debates (Söderbaum and Shaw, 2003). There is however some confusion regarding its meaning as well as its divergence from ‘old regionalism’. It must be emphasized from the outset that regionalism is by no means a new phenomenon. Cross-‘national’ (cross-community) interactions and interdependencies have existed as far back as the earliest historical recordings. In some instances, new regionalism is employed in the temporal sense with reference to the current era or wave of regionalism. There are a number of problems that are readily apparent with this type of labeling. First and foremost, there are often strong continuities and similarities between older and more recent forms of regionalism. By focusing solely on either past or present eras, one runs the risk of obscuring important transitions and possible concurrences between regionalisms. It is also possible to speak of new regionalism in a spatial sense, referring to a region – a veritable emerging region – that did not previously experience regionalism or has experienced a form of regionalism that was imposed by external forces. This dimension is relevant insofar as the regional phenomenon is now being transformed in the image of the European project and model during the first wave of regionalism towards a more global and diverse phenomenon.

The term new regionalism is perhaps most relevant to use for theoretical reasons. It is a widely used theory-building strategy in the social sciences to add the prefix ‘new’ in order to distinguish theoretical novelties from previous frameworks. This strategy is used both by mainstream and critical scholars in the discourse of regionalism. By consequence, we need to distinguish between mainstream theories of new regionalism and the new regionalism/regionalisms approach (NRA) as used in this volume (Söderbaum, 2002; Söderbaum and Shaw, 2003). Our definition of the NRA is a rather diffused school of regionalism espoused by scholars of critical and non-orthodox IR/IPE. Its origins can be traced to the United Nations University/World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER)-sponsored research project on the New Regionalism (Hettne and Inotai, 1994; Hettne et al, 1999, 2000a, 2000b, 2000c and 2001; Hettne and Söderbaum, 1998 and 2000; Mittelman, 2000; Schulz et al, 2001; Söderbaum, 2002; Thompson, 2000). Subsequently, some scholars have made a call for a ‘new regionalisms’ approach (Bøås et al, 1999; Bøås, 2000; Shaw, 2000a and 2000b). While applauding the NRA, this cohort has placed additional emphasis on the pluralistic and informal nature of contemporary regionalization as it is occurring in the South. However, it must be emphasized that the researchers spearheading the two ‘approaches’ are linked in varying degrees to more or less the same epistemic network. The stance of this volume is to draw attention to the similarities rather than relatively minor (and in-group) differences between these two strands of thinking (for clarifications, see Söderbaum, 2002; Söderbaum and Shaw, 2003). The contention regarding the pluralism of new regionalism is a nonissue for us, since both strands of thinking are equally flexible for the aims and objectives of this book. Thus, the NRA as defined in this collection is referring to both of these theoretical ‘strands’ or ‘approaches’.

Transcending State-Centrism and Formal Regionalism

Most approaches in the research field have been excessively concerned with formal and states-centric notions of regionalism. As Bach (1999a: 1) correctly points out: ‘Outside Europe, the rebirth of regionalism during the late 1980s often had little to do with the numerous international organizations that were supposed to promote its development’. Clapham (1999: 53) draws attention to the same issue:

The model of inter-state integration through formal institutional frameworks, which has hitherto dominated the analysis of integration in Africa and elsewhere, has increasingly been challenged by the declining control of states over their own territories, the proliferation of informal networks, and the incorporation of Africa (on a highly subordinate basis) into the emerging global order.

It should thus be evident that the NRA looks beyond state-centrism. It is difficult to dispute that the nation-state is being re-structured and often lacks the capacity to handle global challenges to national interests. The NRA suggests that in the context of globalization, the state is being ‘unbundled’, with the result that actors other than the state are gaining strength. By implication, the focus should not be only on state actors and formal regionalism, but also on non-state actors and what is broadly referred to as ‘informal regionalism’ or ‘regionalism from below’. This includes a wide range of non-state actors and activities, such as transnational corporations (TNCs), ethnic business networks, civil societies, think-tanks, private armies, development corridors and the informal border politics of small-scale trade, bartering, smuggling and crime. In other words:

It is only when we make deliberate attempts to connect the two broad processes of formal and informal regional isms that we can get a clearer picture of the connections between them.... The point is that the outcome of these processes is highly unpredictable, and most often there is more to these issues than meets the eye (Bøås et al, 1999: 905-6).

This perspective is highly relevant in the African context. Despite the recent fanfare surrounding the transformation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) to the African Union (AU), at least the more cautious commentators are pessimistic that the new entity will be able to attain its vaunted goals of a highly developed institutional framework – modeled on the European Union (EU) – with attendant economic and political integration. The largely dismal track-record of other regional African ventures, such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), only contributes to the general lack of confidence in formal states-led regionalization in Africa. In contrast, witness the more informal processes of regionalization ranging from illicit trade networks in ‘blood’ diamonds and other commodities to gray markets in terms of arms sales to nascent regional trade corridors, war zones and regional conflicts (e.g., the spread of HIV/AIDS by intervening African military forces in the Democratic Republic of the Congo). An important component of the NRA is that it obviates the artificial separation of state and non-state actors associated with traditional or conventional regional approaches and recognizes that formal and informal aspects of regionalization are often intertwined (Bach, 1999a; Bayart et al, 1999; Chabal and Daloz, 1999; Grant, 2000; MacGaffey and Bazenguissa-Ganga, 2000; Shaw, 2000a; Söderbaum, 2002).

This volume argues that conventional or problem-solving theories of regionalism do not portray accurately the overlapping processes of regionalization that continue to evolve across Africa. This is by no means equivalent to claiming that states and inter-governmental organizations are not crucial actors or important objects of analysis in the process of regionalization. On the contrary, the state as well as the forces of state-making and state-destruction are all at the core of understanding regionalism. However, this volume shows that the state can be an interest group acting together with other states and non-state actors for private gain rather than the public good or state security as is often prescribed in liberal and realist theory. Mainstream theories are often based on highly normative assumptions about the state, and therefore, tend to generate highly normative assumptions about regionalism. In our view, the state needs to be problematized. The state cannot be taken for granted; it is often a different animal than it pretends to be. Likewise, we need to avoid assumptions a priori of who is the dominant and ‘driving’ regionalizing actor. State actors are important, but so are non-state actors, and various types of actors often come together in diverse and complex mixed- actor coalitions and networks.

Regions, Regionalism and Regionalization

The concept and the content of the ‘region’ are fundamental to the study of regionalism. Much research capacity has been devoted to determining what ‘types’ of regions are the most functional, instrumental and efficient (to govern). Often, especially in political science and economics, regions are taken as ipso facto or (pre-)given, defined in advance of research and, as noted above, very often seen simply as particular inter-state frameworks. Integral to this reasoning is that regions are believed to exist ‘out there’, identifiable through material structures and inter-state frameworks. The concept of region often refers to macro-regions (world regions), which are larger territorial (in contrast with non-territorial) units or sub-systems between the ‘state’ and the ‘global’ system level. In IR, the macroregion has been the most common object of analysis. Nevertheless, it must be recognized that regions exist at different spatial levels. There is some discussion in this volume of macro-regional entities that encompass the entire continent, such as the OAU and its recent successor, the AU. If the AU is a macro-regional grouping, then Southern Africa is a sub-region, meso-region or simply one of the continent’s five major regions. However, Southern Africa is most frequently considered a macro-regional space in its own right, thereby encompassing distinct sub-regions, such as the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) area. Therefore, the concept of sub-region only makes sense when related to larger macro-regions. Furthermore, micro-regions refer to a space between the ‘national’ and the ‘local’. Historically speaking, micro-regions have primarily existed within particular states (i.e., subnational micro-regions). However, in the post-Cold War era and in the context of globalization and regionalization, micro-regions are becoming increasingly cross- border in nature. This volume considers different micro-regions, such as spatial development initiatives (SDIs), trans-frontier conservation areas (TFCAs)/peace parks and enclaves, but it does so in the context of other types of regionalization. In other words, the volume attempts to bridge the gap between the often separated discourses and levels of regionalism. Macro-regions, sub/meso-regions and microregions are related and intertwined to an increasing extent, together constituting parts of the larger process of regionalization.

Contrary to the mainstream focus on states-led regionalism, regional institutions and policy-driven trading schemes, the NRA is more eclectic and more concerned with the dynamics and consequences of processes of regionalization in various fields of activity and at various levels. The puzzle is to understand and explain the phenomenon of regionalism and the process through which regions are coming into existence and are being consolidated – their ‘becoming’ so to speak – rather than a particular set of activities and flows within a pre-given (and often pre- scientific) region or regional framework. As Niemann (1998: 115) points out, ‘the existence of regions is preceded by the existence of region-builders’. There are no ‘natural’ or ‘given’ regions, but these are constructed, de-constructed and reconstructed – intentionally and sometimes even unintentionally – in the process of global transformation by collective human action and identity formation (i.e., regions are constructed both through the ‘outside-in’ and the ‘inside-out’). By no means does the NRA suggest that regions will be unitary, homogeneous or discrete units. Regionalism is a heterogeneous, comprehensive, multi-dimensional phenomenon, taking place in several sectors and often ‘pushed’ (or rather constructed) by a variety of actors (state, market and society). We are likely to experience regionalization at various speeds in various sectors as well as regionalization and de-regionalization occurring at the same time. In other words, integration and disintegration are closely connected and must be analyzed within the same framework (Hettne et al, 1999; Bach, 1999a).

Since regionalism has often been considered beneficial or positive from a normative point of view (especially in liberal thought), this collection will demonstrate that this is by no means necessarily the case. Increased regional interaction and integration may be conflictual, exploitative, reinforce a particular power relation or create other negative effects. Some actors will undoubtedly lose from regionalism, while others will benefit. This is not to say that regionalism is a zero-sum game. Rather, among the panoply of actors involved in the regional project at hand, whether state or non-state, formal or informal, some will gain (and some more than others) and some will lose (and some more than others). While we do not claim that these actors are rational choice-makers in the strict meaning and application of the term, we cannot ignore the outcomes associated with regional processes in terms of varying relative gains and losses across the spectrum of spatial levels. Witness the proliferation of West African criminal networks in Southern Africa, which defies traditional or orthodox explanations of regionalism. Aside from the criminals who benefit from the illicit drug trade and the so-called ‘advanced fee’ fraud, agents of the state (government officials and civil servants) may become involved in these regional networks as well (Shaw, 2002). The flexibility of the NRA is better equipped to explore the implications of the type of regionalism that occurs when state and non-state actors become blurred under the aegis of the ‘criminalization’ of the state or regional criminal networks.

Before proceeding further, regionalism and regionalization need to be defined. ‘Regionalism’, as a generic term and in the broadest possible sense, refers to the general phenomenon of regionalism (e.g., contemporary regionalism or the new regionalism). As such, it cannot be used as an operational tool. In a more narrow and operational sense, regionalism represents the body of ideas, values and concrete objectives that are aimed at transforming a geographical area into a clearly identified regional social space. In other words, it is the urge by any set of actors to re-organize along regional lines in any given issue-area. Regionalization implies a dynamic element, the pursuit of regionalization, creating a regional system or network in a specific geographical area or regional social space, either issue-specific or more general in scope. Regionalization may be caused by regionalism, but it may also emerge regardless of whether there is a regionalist project and ideology present (Hveem, 2000: 73). Regionalization can occur unintentionally, without actors necessarily being conscious of or dedicated to regionalism. Likewise, the rhetoric and ideology of regionalism may not always have much significance for the reality of regionalization in practice.