![]()

Part I

Sumptuary Legislation and the Tudor Social Structure

![]()

Chapter 1

Costly Array: The Henrician Sumptuary Legislation

Sumptuary legislation was not a new idea in the sixteenth century. Indeed, centuries before, Roman legislators had addressed many of the concerns about excesses in apparel that were worrying governments across early modern Europe. The lex Julia or Julian law of 46 BC sought to control access to luxury fabrics and the colour purple, while the emperor Tiberius banned men from wearing silk and Nero restricted use of the purple dyes amethystine and Tyrian purple.1 With the rise of Christianity, wanting and wearing fine clothes were considered to be evidence of luxury which was synonymous with lust, one of the seven deadly sins. In spite of this, sumptuary legislation has been described as an ‘identifying characteristic’ of the early modern period.2 So it is not surprising that Henry VIII passed four sumptuary laws or acts of apparel in 1510, 1514, 1515 and 1533 (Table 1.1 – pages 29–39).3 The laws were hierarchical in their structure, with social status being directly linked to the quality of cloth that an individual was allowed to wear.4 Expensive, imported silks, furs and metal thread acted as material signifiers of status and the individuals permitted to wear them were clearly identified as the elite. These clothes were an essential expression of social identity but the possession of the clothes alone would not make a man, or a woman for that matter, a member of the elite.

The English acts of apparel provide information about social status, gender relations and levels of urbanization.5 More specifically, the acts were anti-consumption legislation or legislation aimed at controlling consumption by social groups that were spending money on clothing and accessories at a level above their income and their station. The first sumptuary law or act of apparel was passed by Edward III in 1337 and the last act was repealed in 1604 by James I. During this 267 year period, the series of 18 laws made explicit the link between rank and dress and the legislators sought to use parliament as the means of controlling the people’s clothing (Illustration 1.1).6 The various ideas motivating the legislation were listed in the preambles to the acts and these considerations were predominantly economic (Documents 1.1 and 1.2). The legislators sought to protect the English wool trade by limiting access to imported clothes and cloth. Indeed, this process had begun in 1326 with an ordinance banning the purchase of fabric produced outside England, Ireland or Wales.7 They also wished to prevent the impoverishment of the population by encouraging people to live within their means. A sure way of doing this was to limit the textiles that an individual could wear, which emphasizes the high cost of material and clothing at this time. The laws also reflected contemporary attitudes to the social structure and the preamble to the 1533 act emphasized the need to distinguish between ‘estates, pre-eminence, dignities and degrees’. Finally, the legislation had a moral underpinning as the legislators sought to protect people from being tempted into luxurious behaviour which could result in poverty and crime. opulent or inappropriate dress was seen as evidence of the sin of pride and so it was important to encourage people to live modest, virtuous lives.

The law of 1337 was short, simple in format and it aimed to restrict access to imported cloth and furs.8 However, in 1363 it was succeeded by an act that made the first link between the social structure, income and access to specific materials.9 This structure was repeated in the Edwardian legislation of 1463 and 1483. In 1463 the act passed by Edward IV restricted the wearing of velvet, ‘satern fugery or fugerie’ or counterfeit silk to men of the rank of knight or above.10 Unusually, there was a reference to female clothing in the act of 1483 which sought to regulate the clothes of the wives and daughters of husbandmen and labourers. It also discussed the morality of late fifteenth-century male clothing and it banned ‘any Gown or mantle unless it be of such Length, that, he being upright, it shall cover his privy Members and buttocks’ to men below the rank of lord.

The Henrician legislation was modelled on the Edwardian acts of apparel. The acts reveal a growing concern with emphasizing the increasingly subtle definitions of rank within the nobility and gentry. All of the emphasis was placed upon preserving the landed social structure, while the rising urban and mercantile elite were ignored.11 The law of 1510 made very clear what comprised royal dress: the colour purple. Later laws expanded upon the theme and included cloth of tissue and sables. Equally, the king could ‘grant and give licence and authority to such of his subjects as his grace think convenient to wear all and such singular apparell on his body or his horse as shall stand with the pleasure of the king’s grace’.12 As such the legislation was newsworthy and on

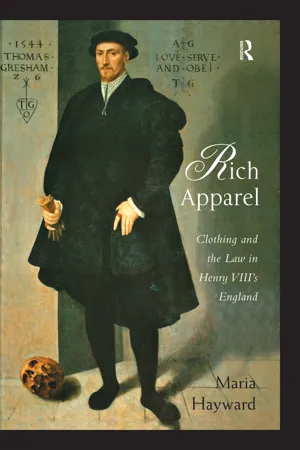

Illustration 1.1 Henry VIII in parliament, unknown artist, c.1532. [The Wriothesley Garter Book, RCIN 1047414]. The Royal Collection © 2008 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

15 December 1515 Lorenzo Pasqualigo wrote to his brother Francasco commenting on the impact that the sumptuary laws would have on the Genoese if the controls on wearing silk were enforced.13 The king and his court were dressed ‘in long grey cloth gowns in the Hungarian fashion’ to set an example but this did not last long. Henry VIII’s third act of apparel, passed in 1515, was noteworthy enough for Hall to record in his Chronicle that it was ‘much spoken of’.14

Henry VIII took a personal interest in the sumptuary legislation and his two chief ministers ensured that he had the necessary papers. In 1515 Wolsey sent a copy of the sumptuary legislation statutes to the king for his approval so that he could ‘examyn reforme and correct such poyntes [that were] not mete to passe’.15 Sixteen years later, in 1531 Henry VIII told Cromwell that ‘the bill of apparel be…put in readiness against the beginning of the next Parliament’.16 In addition to the acts of apparel, ten proclamations were issued between 1550 and 1588 repeating the provisions made in 1533.17 However, the inefficiency of proclamations to enforce laws was hinted at by the act passed in 1539 which was intended to enforce royal proclamations.18

Henry VIII also sought to regulate the conspicuous consumption of food at banquets held by members of the social elite and in May 1517 this was reinforced with a proclamation.19 The social structure presented in the food-related legislation emphasized key groups within the secular and ecclesiastical hierarchies. However the emphasis was somewhat different to that presented within the acts of apparel and it did not extend as far down the social order. Tellingly, in view of Wolsey’s influence at this time, the act began with the provision for cardinals, continuing with archbishops and dukes; marquesses, earls and bishops; all other lords temporal under the degree of earl, abbots who sat in parliament, the current mayor of London and knights of the Garter; judges, the chief baron of the exchequer, the king’s council and the sheriff of London, right down to all those spiritual and temporal with goods to the value of £500 who might dine as if they had £40 to spend. As such it covered the clergy and laity equally as well as the urban elite.

In 1552 Edward VI drafted a bill for restraint of apparel in his own hand. It echoed those of his father but it was shorter, less detailed and it did not make any significant additions to the 1533 act.20 Small details highlighted new items that were desirable, such as ostrich feathers, which were restricted to gentlemen and above, while girdles and scabbards were denied to serving men. It looked back to Edward IV’s law of 1483 when it stated that the wives of husbandmen and shepherds ‘may weare that their husbands doe, and so may thair sonnes and daughters, being under their tuition’. In 1574 the Elizabethan laws took a different turn with the inclusion of female dress.21 It is not surprising that a queen with such a well-developed interest in her own appearance and wardrobe as Elizabeth I should want to control how her fellow females dressed. This regulation was intended to ensure that no-one could rival her appearance at court.

The position of men and women

Tudor society placed a heavy emphasis on masculinity and patriarchy. In 1526 William Tyndale’s English translation of the New Testament made the first reference in St Paul’s letter to the Ephesians to women being ‘the weaker vessel’.22 One of the consequences of being seen as weaker meant that women were expected to be biddable to their male relatives and this was reflected by Edward VI’s legislation, which noted that English men’s ‘wives may weare [what] their husbands does … being under their tuition’.23 This does not mean that Tudor women always did as they were told, which explains why Sir Thomas More noted in his Epigrammata that ‘If you let your wife stand on your toe tonight, she’ll stand on your face first thing tomorrow morning.’24

The exclusion of women from the Henrician sumptuary legislation reflects that their social standing was inferior to that of men. The 1510 act of apparel stated that it should not be ‘prejudiciall nor hurtfull to eny Woman’.25 Women were not even mentioned in the other three sets of Henrician legislation. Even so, women still conformed to the Tudor social structure. First, their status was linked to that of their father and then th...

![Illustration 1.1 Henry VIII in parliament, unknown artist, c.1532. [The Wriothesley Garter Book, RCIN 1047414]. The Royal Collection © 2008 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1495741/images/illustration1_1-plgo-compressed.webp)