- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Religion: Empirical Studies

About this book

Treating 'religion' as a fully social, cultural, historical and material field of practice, this book presents a series of debates and positions on the nature and purpose of the 'Study of Religions', or 'Religious Studies'. Offering an introductory guide to this influential, and politically relevant, academic field, the contributors illustrate the diversity and theoretical viability of qualitative empirical methodologies in the study of religions. The historical and cultural circumstances attending the emergence, defence, and future prospects of Religious Studies are documented, drawing on theoretical material and case studies prepared within the context of the British Association for the Study of Religions (BASR), and making frequent reference to wider European, North American, and other international debates and critiques.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART one

Category and Method

1

Phenomenology, Fieldwork and Folk Religion

Introduction: Defining ‘Folk Religion’

This chapter was triggered by discussion of phenomenology of religion with Japanese students on the Comparative International Studies programme at Bath College of Higher Education (subsequently Bath Spa University College). When the time came for examination revision in Study of Religions, we dutifully went over various points concerning phenomenology – epoche, eidetic vision, Smart’s dimensions and so on. I told the students they would have to be prepared to discuss the pros and cons of phenomenology, and this produced some interesting reactions. One student was perplexed, as she could only think of positive things to say of phenomenology. Another, however, put forward the old accusation that phenomenology was merely descriptive.

Descriptive – yes; merely descriptive – no. I am not for a moment suggesting that there is no need or place for analysis in the study of religious traditions. I am, however, suggesting that it is necessary to remember that description, in the sense of accurate, judgement-free reporting, is invaluable in the study of religions. Analysis without phenomenological fieldwork can be suspect at best, dangerous at worst. Unless we check our analyses against what is actually happening in the field, we risk perpetuating false assumptions and blatant inaccuracies.

The need I perceive for phenomenological fieldwork stems from my own particular area of interest, which is popular or folk religion, by which I mean what people actually do, say, think, believe in the name of religion. Another way of putting it might be to say that I am interested in the Little Tradition, but the Little Tradition does not exist in isolation from the Great Tradition and vice versa, so that is not how I would normally choose to put it. These are not terms with which I feel particularly comfortable. Having read Religious Studies at Lancaster University and Folklore at Memorial University of Newfoundland,1 I am happier with the term folk religion. Don Yoder (1974a, p. 14) defines folk religion as ‘the totality of all those views and practices of religion that exist among the people apart from and alongside the strictly theological and liturgical forms of the official religion’. Obviously, where appropriate, ‘theological and liturgical’ could be replaced by philosophical and ritual.

I am, of course, aware that the term ‘folk religion’ can and has been used in a variety of ways, and that is why I am careful to nail my colours very specifically to Yoder’s mast. In his article ‘The Folk Religion of the English People’, for example, Edward Bailey (1989) comments on the use of the term folk religion among Church of England clergy since the 1970s, citing John Hapgood’s 1983 definition of it as

a general term for the unexpressed, inarticulate, but often deeply felt religion of ordinary folk who would not usually describe themselves as Church-going Christians yet feel themselves to have some sort of Christian allegiance.

While rejecting this as too narrow a view of what folk religion is, it is only fair to point out that Yoder’s definition is itself based on the German term ‘religiose Volkskunde’, which he translates as ‘the folk-cultural dimension of religion, or the religious dimension of folk culture’ (1974a, p. 14). This term was originally coined in 1901 by a German Lutheran minister, Paul Drews, whose concern was to investigate religious folklife so that young ministers were better equipped to deal with rural congregations whose conception of Christianity was often radically different from the clergy’s official version. In Drews’ case, the term folk religion came from ‘an attempt, within organised religion, to narrow the understanding gap between pulpit and pew’ (Yoder 1974a, p. 3). There might still be a need to narrow the understanding gap between the Study of Religions and the religions studied.

I would like to suggest that accounts of religion which do not take into account folk religion risk telling less than the whole story, and that phenomenological fieldwork is often the only means of gathering such information. I have certainly found this to be the case in my own fieldwork experiences.

Three Components of Religion

Frequently, when scholars talk of religion they tend to mean ‘official religion’, usually perceived in terms of theology or philosophy and ritual, which is just one aspect of most people’s religious experience. Believers live according to their own perceptions of the religious traditions to which they adhere, and if their beliefs and practices do not always accord with the official view they remain religious nevertheless; their faith does not become any less sincere or worthy of study. As Susan Tax Freeman (1978, p. 121) has pointed out:

That the personal system of faith may elevate the unsanctioned objects of belief to at least the same level as the sanctioned ones and draw them coherently together has either been ignored or is obliterated by the definitions of religion in use.

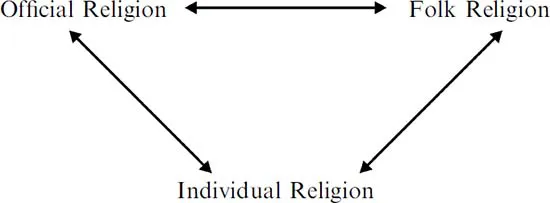

Ninian Smart (1977, p. 11) claims that ‘to understand human history and human life it is necessary to understand religion’. It is tempting to suggest the corollary that to understand religion, it is necessary to understand the relationship between official, folk and individual beliefs and practices. In religion, as in so many aspects of human endeavour, theory and practice do not necessarily coincide, nor do people behave in exactly the same way. To study the practice as opposed to the theory of religion, ‘ordinary’ people’s ideas and behaviour must be taken into account. It is thus helpful to view religion in terms of three basic components – the official, the folk and the individual. Official religion is concerned primarily with theology/philosophy and ritual, and is the aspect of religion which tends to receive most scholarly attention. Folk religion can be described as ‘the totality of all those views and practices of religion that exist among the people apart from and alongside the strictly theological and liturgical forms of the official religion’ (Yoder 1974a, p. 14), a vast but comparatively neglected field. The individual component is basically each person’s understanding of religion and the part it plays in his or her life.

These components are rarely analysed, or indeed recognised, in relation to each other. Believers and observers have tended to be unaware of the extent to which these components are interrelated, and this can lead to inaccurate and/or misleading appraisals of religious phenomena. In order to comprehend religion in its broadest sense it is necessary to appreciate how official, folk and individual ideas and behaviour interact with each other.

There is a carefully cultivated ‘solidity’ about official religion, but it is not a well-defined, static entity. Theological notions can be developed, modified or abandoned. Previously condoned ideas or practices can be actively opposed, or just quietly dropped. However, a belief can continue to be acted upon, regardless of the fact that it is no longer officially approved. It slips from official to folk religion. Conversely, folk religious ideas and practices can gain approval and become official. The process works both ways. Folk religion thus ‘exists in creative tension with official religion and involves a body of belief and practice that overlaps with that of official religion in both directions – the permitted forms overlapping inward into official religion, the unpermitted or unsanctioned forms remaining outside the strict edge of official religion’(Yoder 1974b, p. 1).

At the individual level, religion is a mixture of a received religious tradition and a personal belief system. In talking of the ‘received’ tradition, I am making the point that in many cases what the individual learns of religion does not come from purely orthodox sources. Relatives, contemporaries and others make their mark by example and by passing on their interpretations of religious matters, and it can be quite difficult for the individual to know what actually comprises ‘official’ religion. The personal belief system evolves from the received tradition, but it is affected by the individual’s particular outlook, experience and suchlike. Even if a number of people were to receive a similar tradition, there would still be scope for individual interpretations of it, ‘for each person’s religion has to do with himself and his own autonomous needs’ (Douglas 1973, p. 26). On occasion the ideas of an individual, such as Augustine or Aquinas in the Christian tradition, can radically affect official religion. A personal belief or practice can likewise pass into folk religion.

In diagrammatic form, the relationship between official, folk and individual religion might be expressed thus:

In drawing attention to the relationship between official and folk religion, and the lack of standardisation in people’s received traditions and personal belief systems, I wish to make the point that there is considerable scope for variety and variation in religion.2 Indeed, it seems almost inevitable. However, there is a tendency towards concentration on homogeneity in religion and minimisation of diversity. But there is no such thing as pure religion, whatever the religious tradition. Official, folk and individual components interact to produce what, for each person, constitutes religion. To understand religion in its broadest sense it is therefore necessary to take into account not just theology or philosophy and ritual, but the perceptions, beliefs and behaviour of those practising it. I am not, of course, suggesting that to say anything about any religion it is necessary to talk to everyone involved. I am, however, appealing for a realistic view of religion, and the recognition that folk religion, as defined by Yoder, is not an aberration, but an important and constant element of religion per se. In other words, folk religion should be a descriptive, not a pejorative term.

Case Study: Devotion to Saint Gerard Majella in Newfoundland

This brings us back to the value of phenomenology. The subject of my MA thesis was devotion to St Gerard Majella in Newfoundland. In brief, St Gerard was born in Muro, Southern Italy, in 1726; a remarkably pious child and exemplary adolescent who suffered from delicate health, he became a Redemptorist lay brother but died in 1755. He was not beatified until 1893 and was finally canonised in 1904. Although a seemingly incongruous role for a sickly male virgin who died young, he has been best known and most vigorously promoted in Newfoundland as Patron of Expectant Mothers. I first became aware of him because it seemed to me that a disproportionately high number of Newfoundlanders were named Gerard, and this impression was confirmed by others. A St John’s judge, for example, claimed that ‘every other young fellow hauled up’ before him was a Gerard, while a female friend remarked that ‘practically every second chap’ in her community was a Gerard. The names were a reflection of the high level of devotion to St Gerard.

Much of what has been written of the saint system has either been by Catholic apologists or by theologians and historians complaining of‘abuses’ of it at popular level.3 As a result, we know comparatively little of how the saint system has operated in the lives of ordinary Catholics. The range of beliefs and practices associated with this type of devotion has received comparatively little attention. This is partly because religion has often been studied in terms of what people should do or think; whatever has not conformed to that has either been condemned or, more frequently, simply ignored.

There are also practical difficulties. It can at times be very hard to judge whether some aspect of religious belief is official, folk, or simply idiosyncratic; the boundaries between official, folk and individual religion are not well-defined and they can be virtually indistinguishable. Frequently folk ideas and behaviour are so much part of a religious tradition that participants and observers alike consider them normative. In addition, much of religious life takes place outside ritual settings and is not easily observable. Religion can be very a personal matter, and it is therefore necessary to consult those involved in religious activity to ascertain what is actually happening. Since the relationship between an individual and a holy or supernatural figure in whatever tradition is essentially a personal affair, the minutiae of devotion and the part it plays in the lives of individuals can only be discovered through consultation with devotees.

In the study of folk and individual beliefs and practices, the flesh on the bare bones of official religion, I believe that phenomenology provides an invaluable methodological basis. While what follows is probably now so familiar as to seem like a collection of cliches, let me nevertheless restate some of its underlying principles. Phenomenology of religion, Bleeker (1971, p. 16) claims, ‘must begin by accepting as proper objects of study all phenomena that are professed to be religious’. As it ‘attempts to describe religious behavior rather than explain it’ (Bettis 1969, p. 3), debates as to the existence or reality of the focus of devotion are futile and inappropriate. As Smart (1973, p. 54) points out, ‘God is real for Christians whether or not he exists.’ We do well to remember that scepticism is every bit as biased an outlook as belief. The personal experience narratives of devotees of whatever persuasion provide evidence which must have the status of religious fact. As Kristensen cautioned, ‘Let us never forget that there exists no other religious reality than the faith of the believer’ (quoted in Sharpe 1986, p. 228). One can analyse and contextualise, certainly, but to condemn, dismiss or ignore the experiences of those living a religion is to diminish our understanding of the tradition, and to tamper with evidence in a way which we would consider improper in other disciplines.

When I first started interviewing Newfoundland women about their devotion to St Gerard, I quite expected some reticence as I was asking about deeply personal matters, but people were remarkably candid and forthcoming. Women generally seemed pleased to share their experiences with an interested listener, such as the one who started ‘Oh yes, we had a miracle here a few years back’ with the same ap...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Religion: Empirical Studies

- Foreword

- Introduction: Qualitative Empirical Methodologies: An Inductive Argument

- PART one Category and Method

- PART two Case Studies

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Religion: Empirical Studies by Steven J. Sutcliffe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.