- 656 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dickens and Childhood

About this book

'No words can express the secret agony of my soul'. Dickens's tantalising hint alluding to his time at Warren's Blacking Factory remains a gnomic statement until Forster's biography after Dickens's death. Such a revelation partly explains the dominance of biography in early Dickens criticism; Dickens's own childhood was understood to provide the material for his writing, particularly his representation of the child and childhood. Yet childhood in Dickens continues to generate a significant level of critical interest. This volume of essays traces the shifting importance given to childhood in Dickens criticism. The essays consider a range of subjects such as the Romantic child, the child and the family, and the child as a vehicle for social criticism, as well as current issues such as empire, race and difference, and death. Written by leading researchers and educators, this selection of previously published articles and book chapters is representative of key developments in this field. Given the perennial importance of the child in Dickens this volume is an indispensable reference work for Dickens specialists and aficionados alike.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Biography

1

Early Years: London, 1822–1827

When I tread the old ground, I do not wonder that I seem to see and pity, going on before me, an innocent romantic boy, making his imaginative world out of such strange experiences and sordid things!

David Copperfield, ch.11

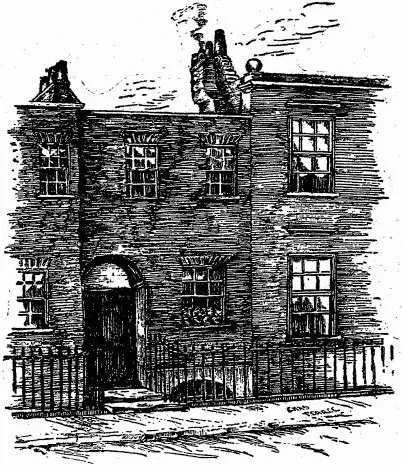

THE DICKENSES’ new home, 16 Bayham Street in Camden Town, was appreciably smaller than their last house in Chatham, though the rateable value (£22 p.a.) was higher than that of the Ordnance Terrace house (£5. 10s.). John Dickens needed to retrench but the evidence indicates that he was soon running up bills with his baker and other tradesmen. For her part, Elizabeth Dickens continued to be landlady as well as wife and mother and so arranged the new home that, even within the confined space of its four rooms on two floors, young Lamert could continue lodging with the family, at least for the time being. He probably had the front room on the first floor, as Tommy Traddles does in Copperfield (ch. 27) when he lodges with the Micawbers in Camden Town, in a house Dickens seems to have based on his memories of Bayham Street. The family, now six in all, would have been squeezed into the remaining accommodation and the little orphan maid-of-all-work whose ‘sharp little worldly and also kindly ways’ Dickens was later to recall when depicting the Marchioness in The Old Curiosity Shop would have bedded down in the basement kitchen. Dickens himself slept in a kind of rear garret which had its own little staircase but was no more than a sort of cupboard some four and a half feet high, hanging over the [main] stairway’.1

Forster, doubtless echoing what he had often heard from Dickens himself, described the area as being then ‘about the poorest part of the London suburbs’ and the house itself as ‘a mean small tenement, with a wretched little back-garden abutting on a squalid court’. This description of Bayham Street and its environs was objected to by some Daily Telegraph readers when Forster published it in vol.1 of his Life of Dickens. One reader signing himself or herself ‘F. M.’ called it ‘a perfect caricature of a quiet street in what was then but a village’ while another opined that such a grim description ‘must have been prompted by [Dickens’s] personal privations’.2

3 16 Bayham Street, Camden Town

Forster’s treatment of Bayham Street exemplifies, in fact, the problematic nature of attempting any sort of objective account of Dickens’s life during 1822–24. Over twenty years later Dickens himself wrote very powerfully and eloquently about this period in the so-called ‘autobiographical fragment’ which he used in Copperfield and then gave to Forster (though in quite what form is a puzzle). Forster quotes extensively from it in the second chapter of his Life of Dickens and, since neither anyone involved with the Dickens family at this time nor even anyone who simply came across them has left any record, we have nothing against which to check this strongly emotional account by Dickens himself of his experiences and way of life during these two years. We should also remember that by the time he wrote it he had long been vividly aware of himself as ‘the Inimitable’, a phenomenally gifted and hugely popular creative artist – of being, in fact, what Carlyle was to call ‘a unique of talents’. Moreover, after the profound effect that his 1842 American journey had had upon his sense of self, he had begun, from the time of writing A Christmas Carol onwards, to draw on his own early life for fictional purposes at a much deeper level than before. It is from the standpoint of an established and much-acclaimed literary prodigy, a man in his own words ‘famous and caressed and happy’, that he looks back in anger, grief and pity, as well as something close to incredulity, at what was done to him in his eleventh and twelfth years.3

There must certainly have been much that was bewildering and disturbing about the new family situation for a sensitive and imaginative ten-year-old like Dickens. The abrupt termination of his schooling with, apparently, no plan for its resumption and an only partial comprehension of his father’s increasing financial difficulties – a partial comprehension later turned to richly comic account when he was writing the Micawber chapters of Copperfield – must have been uppermost among his concerns, as well as his sudden isolation from friends of his own age. It may have been about this time, too, that his infant sister Harriet died which, along with the news of Mary Lamert’s death in Ireland in September 1822, would have added further gloom to the already beleaguered household. Then in April 1823 Fanny, his dear companion and confidante, left home, having been admitted as a boarder and piano pupil at the newly-founded Royal Academy of Music. It was not only the loss of her company that would have distressed Dickens but also what must have seemed to him the sheer unfairness of this. Somehow thirty-eight guineas a year could be found to pay Fanny’s board and tuition fees at the Academy but apparently nothing could be spared for the continuance of his education. There would have been a bitter personal resonance for him many years later in what he wrote in chapter 8 of Great Expectations, ‘In the little world in which children have their existence … there is nothing so finely perceived and so finely felt as injustice.’

Today we may well understand how Fanny’s harassed parents must have welcomed Thomas Tomkison’s willingness to recommend her to the Royal Academy of Music. Tomkison was a piano-maker in Dean Street, Soho, and perhaps came to know the Dickenses through Thomas Barrow, who lodged close by in Gerrard Street. The young Dickens could hardly have been expected to reflect that this privileging of Fanny’s education was, from his parents’ point of view, entirely reasonable. Yet, as a close student of Dickens’s early life has observed (surely correctly), ‘Although Charles had given promise of a precocious literary bent… Fanny’s talent as a pianist and her possession of a good soprano voice were deemed to be a surer guarantee of potential earning power.’ In fact, John and Elizabeth had precious little evidence for detecting a ‘precocious literary bent’ in their eldest son. True, he had written Misnar and maybe some other ‘juvenile tragedies’ but this had more to do with his passionate response to theatre than with literature. They would not have seen his two sketches of curious London characters mentioned in the previous chapter (above, p. 1) as he had not dared to show them to anyone. What was remarkable was his talent for comic recitals and comic songs, something that proved to be also very useful at this time for entertaining his godfather Christopher Huffam and his cronies, one of whom pronounced the boy a ‘progidy’. But a career for his eldest son as a ‘professional gentleman’ entertaining the boozy patrons of ‘harmonic evenings’, like Mr Smuggins in Sketches by Boz or Little Swills in Bleak House, would hardly have been something that even the convivial and generally easy-going John would have contemplated with equanimity.4

So the puzzled boy was left alone to fall into a mooching way of life, in which he would often, as he later told Forster, spend time gazing dreamily at the distant city of London from a spot near some almshouses at the top of Bayham Street, ‘a treat that served him for hours of vague reflection afterwards’. He made himself useful about the house, cleaned his father’s shoes, and ran domestic errands, all the time doubtless feeling both bewilderment and hurt that no-one seemed to have any plans for him. He knew he had a ‘kind-hearted and generous’ father who had watched by him when he was ill ‘unweariedly and patiently, many days and nights’, and who had encouraged him to dream of one day coming to live in a fine house like Gad’s Hill if he worked hard enough. Yet this same father seemed, he later wrote, ‘in the ease of his temper and the straitness of his means … to have utterly lost at this time the idea of educating me at all, and to have utterly put from him the notion that I had any claim upon him, in that regard, whatever.’ Whether this was John Dickens’s actual state of mind with respect to his eldest son or whether, as is most likely, he was simply unable to pay a second set of tuition fees we cannot now know. Nor can we know what answer he gave when Dickens asked him, as surely he must have done, when he was going back to school. All we know for sure is that, whatever the situation was at the time, the way Dickens recalled it twenty years or so later was that John’s attitude towards his education seemed, incomprehensibly, to have been one of total obliviousness.5

Dickens’s life, if devoid of schooling, was not without its treats and pleasures at this time, however. Lamert made a toy theatre for him to play with, and perhaps even took him again to some actual theatres. He found a new source for books, among them Jane Porter’s Scottish Chiefs and Holbein’s Dance of Death, borrowing them from Uncle Thomas Barrow’s landlady in Gerrard Street, who was a bookseller’s widow (he went there often to visit and help Barrow, laid up with a broken leg). Many of these pleasures can be related directly to his later emergence as the supreme novelist of London, the writer who, both as novelist and journalist, was to describe the city ‘like a special correspondent for posterity’. Among the books he borrowed was the same collection of comic verse, Colman’s Broad Grins, in which his father had found the recitation piece with which he had scored such a triumph at the ‘annual display’ at Giles’s school in Chatham. Whether or not this now gave him a pang, he was entranced by the description of Covent Garden he found in another of Colman’s doggerel poems and one time ‘stole down to the market by himself to compare it with the book’. Telling Forster this, he remembered how he went ‘snuffing up the flavour of the faded cabbage-leaves as if it were the very breath of comic fiction’. This seems to have been a solo expedition, as perhaps were his visits to Gerrard Street, but more usually he was accompanied by an adult – sometimes James Lamert perhaps – on visits to the city, responding with fascination and delight to all the sights and sounds of the place. In particular, he was strongly attracted (the ‘attraction of repulsion’ as Forster calls it) to the socalled ‘rookery’ or labyrinthine slum sheltering many criminals of St Giles, located at the southern end of the Tottenham Court Road, the kind of locality he was later to describe in his 1841 preface to Oliver Twist as full of ‘foul and frowsy dens, where vice is closely packed and lacks the room to turn’. Forster records him as saying that ‘if he could only induce whomsoever took him out to take him through Seven-dials [an area forming part of the “rookery” or crime-infested slum of St Giles and later the subject of one of his Boz sketches], he was supremely happy: “Good Heaven!” he would exclaim, “what wild visions of prodigies of wickedness, want, and beggary, arose in my mind out of that place!” He loved also the visits to Godfather Huffam in Limehouse which gave him glimpses of the riverside and boatyard life there while “the London night-sights as he returned were a perpetual joy and marvel”. These visits must have seemed a bit like the old days at the Mitre in Chatham come back again as Huffam’s friends applauded the boy’s comic singing, and his kindly godfather gave him also more tangible proof of his appreciation in the form of a very handsome half-crown tip. Huffam was, as Dickens was to put it later, the kind of godfather “who knew his duty and did it”.6

The essay in which this phrase appears is ‘Gone Astray’, which Dickens published in his magazine Household Words on 13 August 1853. Written in the first person, it purports to describe, ‘literally and exactly’, how the writer was taken as a child for a sight-seeing walk in London, got accidentally separated from his escort, and spent a whole day wandering about the city with his head full of stories about Dick Whittington and Sinbad the Sailor and wondering at all the mysteries and marvels of the place like the huge images of the giants Gog and Magog in the Guildhall. Whether this essay was based on an actual experience of being lost we do not know but one distinguished Dickens scholar has noted that the vividness of his description of little Florence Dombey’s feelings when she finds herself lost in a similar situation (Dombey and Son, ch. 6) suggests that he is indeed remembering an actual occurrence. However this may be, what is certainly true is that one of the main effects Dickens seeks to create in ‘Gone Astray’ is to make the reader experience a romantic child’s thrilled and attentive response to the city with all its multitudinous wonders and dangers and this is something that we may certainly take as reflecting autobiographical truth.7

For it was at this time that Dickens’s lifelong fascination with the sights and sounds of London, and with the myriad strange human life-forms bred or shaped by the city, really took hold of him, and even found its first expression in writing. As already noted in the previous chapter, he tried his hand at sketching a couple of ripe London characters. He came across the eccentric old barber (who may have been none other than the father of Turner) through Thomas Barrow, who was shaved by him. The deaf old woman who helped his mother in Bayham Street had a skill in making ‘delicate hashes with walnut-ketchup’ that put Dickens in mind of a character in one of his favourite stories Le Sage’s Gil Blas, the pampered canon’s housekeeper who could soften dishes down ‘to the most delicate or voluptuous palate’. It seems very likely that the old barber, ‘who was never tired of reviewing the events of the last war’, also reminded Dickens of Sterne’s Uncle Toby in another of his favourite books Tristram Shandy (Toby is obsessed by memories of certain events of the Seven Years’ War). We seem to have here, in fact, traces of the earliest example of something that was to become a leading characteristic of Dickens’s later writings both fictional and non-fictional, that is, his use, for a variety of purposes, of literary allusion, especially to Shakespeare and to many of the best-loved books of his childhood such as those just mentioned and The Arabian Nights.8

John Dickens’s affairs, meanwhile, went from bad to worse. He fell behind with payment of the rates and got deeper into debt. He could hardly expect further help from Thomas Barrow nor from his widowed mother, former housekeeper at Crewe Hall, who was now living in retirement in Oxford Street. From her he had, as she recorded in her will in January 1824, already had ‘several Sums of Money some years ago’ and she therefore left him £50 less than she left to his childless elder brother William. To young Charles she gave her husband’s silver watch but no more money to John. In the autumn of 1823 Dickens’s mother, feeling that she must ‘do something’, decided to open a school. Dickens presents this in the autobiographical fragment and in Copperfield as a comically hopeless undertaking and was still mocking it years later, after his mother’s death (in Our Mutual Friend, Bk I, ch.4), even though it really was not such a hare-brained idea. By Dickens’s own account, Elizabeth Dickens was a good teacher and it was reasonable to hope that Christopher Huffam might, through his contacts with parents going out to India, be able to get her some pupils. Bigger and better-situated premises were certainly needed for the purpose, however, and shortly before Chri...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- PART I BIOGRAPHY

- PART II THE ROMANTIC CHILD IN VICTORIAN TIMES

- PART III CHILDHOOD AND THE FAMILY

- PART IV THE CHILD, EMPIRE AND DIFFERENCE

- PART V THE CHILD AS A THEORETICAL VEHICLE

- Name Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Dickens and Childhood by Laura Peters in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.