This is a test

- 910 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book, first published in 1954 with this revised edition published in 1972, was recognised as the standard work on Indo-Pakistani geography. Part 1 focuses on climate and soils; Part 2 provides a synopsis of the social complexities of the sub-continent; Part 3 examines planning and development; Part 4 is devoted to detailed regional description, both urban and rural.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access India and Pakistan by O.H.K. Spate,A.T.A. Learmonth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I The Land

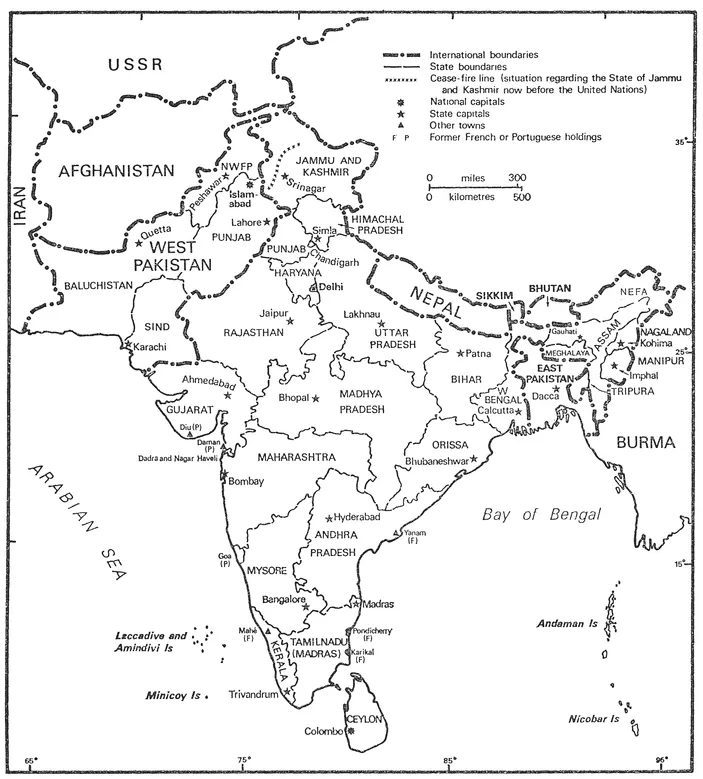

FIG O.I INDIA AND PAKISTAN 1967. I, international boundaries; 2, state boundaries; 3, cease-fire line in Kashmir; 4, national capitals; 5, other towns (those underlined are former French and Portuguese holdings); 6, state capitals; 7, Union Territories (also underlined islands). In November 1966 the Indian Punjab State was divided into a Punjabi-speaking largely Sikh Punjab States, some hill areas being transferred to Himachal Pradesh and the Hindi-speaking east becoming the new State of Hariana. As we go to press with the 1972 reprint, Bangladesh has been recognized by the Indian and various overseas governments as replacing East Pakistan.

Introduction

India as a Unit of Geographical Study

The lands which until August 15th, 1947, formed the Indian Empire, and are now divided into the Commonwealth Republics of India and Pakistan, were never one country until welded together by British power. At long intervals, indeed, a single dynasty secured loose but nearly universal sway; nor did the British themselves administer the sub-continent as a whole, large areas and populations remaining under vassal Indian rulers. But the British connection brought to most of India a common system of administration and law, railways, a common language for the intelligentsia, new forms of economic organization, new ideals of polity. To the extent that these transcended the fantastically interlocking internal divisions, India became one country; in that lay the British achievement.

Persians and Greeks extended the name Sindhu – 'the river' – from the Indus, to which it belonged, to cover such of the land as they knew; and hence the Muslim name Hindustan, properly applied to the area of most firmly based Islamic power in the north. Beyond the Narmada and the Chota Nagpur jungles, which lie across the root of the Peninsula, was the Deccan, the Sanskrit Dakshinapatha or 'Southland'; beyond the Krishna again Tamilnad lived its own life, inheriting the most ancient traditions of Hinduism, perhaps affiliated to the pre-Aryan Indus civilization, itself contemporary with the early empires of Mesopotamia and Egypt. In Hindu literature the sub-continent as a whole is styled Bharata-Varsha, the land of the legendary King Bharata; but it seems safe to say that there was little feeling of identity over the whole country.

Yet for twenty-five centuries at least the entire area, a few margins and enclaves apart, has received the impress of the complex, hardly definable but always easily recognizable culture of Hinduism, which indeed, with Buddhism, once stretched beyond the western borders to the Hindu Kush. Those regions where the cultural landscape displays few or none of the tokens of Hinduism are for the most part mountainous and arid, mountainous and cold, or mountainous and jungle-clad: the Islamic hill country of the western borderlands, the Buddhist high Himalaya in the north, in the east the hills of the Burma border inhabited by a congeries of spirit-worshipping Mongoloid tribes.

Historically, then, it seems pointless to stress the facts that 'India' was rarely (if ever) a single political entity and that its peoples, in common speech at least, had no one name for the whole. For at least two centuries there has been sufficient definiteness about the idea of 'India' to make the area so connoted a feasible unit of study; and despite its partition into two great states, 'India' remains valid as a geographical expression for all the lands between Kanya Kumari (Cape Comorin) and the towering peak K2, respectively in 8° and 36° N.

Isolation and Contact by Land and Sea

Geographically also India is an intelligible isolate. The huge salient of the Peninsula, the keystone of the arch of the Indian Ocean shores, strikes the eye at once; and on the inland borders are the ramparts and fosses of the giant ranges which in large measure wall off the sub-continent from the rest of Asia. These are, however, by no means complete barriers: in that role they are most important as insulating India from the Polar air masses which rule so much of the climate of central Asia, and so ensuring to the sub-continent a practically self-contained monsoon system of its own. But from a human point of view the values of the mountain wall are often determined as much by what lies beyond as by its own topography.

Behind the stupendous bulwarks of the Himalayas lie the vast and all but empty plateaus of wind-swept Tibet, home of a twisted in-bred culture peculiar to itself. Clearly the contacts on this side have been few: a little trade creeping painfully through the high passes – many higher than the loftiest Alpine peaks – and, far more important, seekers of many faiths. To the east the ranges of Assam are much lower, but rain-swept for half the year, and guarded by thick jungle: contact with the Irrawaddy trough is far easier by sea, and it was by sea that the germs of civilization were brought from India to the ancestors of the Burmese, who had gradually filtered down from the marches of Tibet and China.1 On the west the great arcs of Baluchistan, loop on loop of sharp arid ridges cleft by the narrowest and wildest of gorges, are backed by the burning deserts of Seistan; Makran in the south was once more fertile, and through it the Arabs passed to conquer Sind in the 8th century ad. But the great entry lies farther north, guarded on the Indian side by Peshawar and the Indus crossing at Attock.

Here the belt of mountains narrows to under 250 miles (400 km.) between Turkestan and the Punjab, and the core of the mountain zone, the Hindu Kush, is pierced by numerous passes, blocked by snow in winter but in other seasons practicable without great difficulty. Over this Oxus/Indus watershed lies the major passage through which people after people has pressed into the plains of Hindustan, whether impelled by desiccation in the steppe 0r by the political pressures of the constantly shifting fortunes of central Asian war. Of all these incursions, those of prime importance are the organized invasions of various Muslim leaders, culminating in the Mogul Babur's conquest of Hindustan in AD 1526; and the distant folk-wandering of the Aryan-speaking people of the steppes, who had entered certainly by 1000 BC and may have been in at the death of the Indus civilization a few centuries earlier. Horsemen, meat-eaters, mighty drinkers, they contrast strongly with the dark-skinned 'snub-nosed Dasyus', the Dravidian heirs of Indus culture. From the millennial interaction of these two great groups is woven much of the rich tapestry of Hindu myth, and probably also of the darker fabric of caste.

On the whole, then, India is clearly marked off from the rest of Asia by a broad no-man's-land of mountains, whether jungle-covered, ice-bound, or desert; though obviously among the mountain-dwellers themselves no hard and fast line can be drawn dividing those solely or mainly Indian in history and cultural affinity from those solely Burmese, Tibetan, Afghan, or Iranian. The critical area is in the northwestern hills, and here we find in the past great empires slung across the mountains like saddle-bags, with bases of power on the plateau at Kabul or Ghazni or Kandahar, and also in the Punjab plains.

The significance of the mountain barrier, and especially of this great gateway, is clear enough, and more than amply stressed in the British literature, since the Afghan disaster of 1842 almost obsessed with 'the Frontier'. The question of maritime relations is more difficult, and indeed they are often slurred over by easy generalizations about harbourless coasts. But for small craft the west coast is not lacking in harbourage, nor should the delta creeks of the Bay of Bengal be overlooked: Portuguese keels were far from the first to plough the Indian seas. It is true that, until the coming of European seamen, no considerable power was founded in India from the sea; but some were founded from India.

An active trade linked the Graeco-Roman world with Ceylon and southern India, and to Ceylon also came trading fleets from China. In the west – the significantly 'Arabian' Sea – the active agents were Arabs, who may indeed have been the intermediaries for the trade which indubitably existed between the Indus civilization and Sumeria. From the later Middle Ages onwards not only commercial but also political contacts with southwest Asia, and even northeast Africa, were important: an 'African' party played a prominent role in the politics of the Muslim Deccani Kingdoms, and until 1958 a tiny enclave of Oman territory, the Gwadar Peninsula, survived on the Baluchistan coast.

To the east the initiative came from India. Hindu traders and colonizers took their civilization by sea to the southeast Asian lands, and in the first centuries of the Christian era history in Burma, Indonesia and Indo-China begins with these pioneers. A few years before William the Conqueror impressed Europe with the organizing ability displayed in crossing the English Channel, the fleets of the Chola Kingdom in Madras and the equally Indian Kingdom of Sailendra or Sri Vijaya in Sumatra entered upon a century-long struggle across I,000 miles of open ocean. So much for isolation by sea!

The actual node of shipping, however, was and is not in India itself but in Ceylon, and the full exploitation of the key position of India waited until the Indian Ocean was as it were subsumed into the World-Ocean by Vasco da Gama; a reminder of the importance of human and technological elements in locational relations. The reasons for the rapid supersession of Portuguese power by the less spectacular but more efficient Dutch and British are a matter of general European rather than Indian history. But it is worthy of note that the Portuguese, consciously pursuing a Crusade against the Moors, concentrated on the west coast, hemmed in by the Ghats and later by the Marathas, so that they had greater impediments to territorial acquisition than their rivals, even had the pattern of dominion laid down by their second and greatest Viceroy, Afonso de Albuquerque, called for landward expansion. Though Surat, seaward terminal of the great route to Hindustan, was bitterly contested by all three powers, the British were more active on the east coast: and when the Mogul Empire collapsed the land lay open before them.

Diversity and unity in the sub-continent

The isolation of India, then, is but relative; yet isolation there is, and within the girdle of mountains and seas has developed the almost incredibly complex culture of Hinduism: not unaffected by outside influences, certainly, but, in so far as we can dimly descry the origins of some of its yet existing cults in the earliest Indus civilization, native to this soil. Hinduism gives, or until very recently has given; a certain common tone to most of the sub-continent, but it contai...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- PREFACES

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

- TABLES

- CONVENTIONS AND PRELIMINARY DATA

- ABBREVIATIONS

- PART I THE LAND

- PART II THE PEOPLE

- PART IV THE FACE OF THE LAND

- 26 Ceylon

- A Summing-up

- Appendix: Changes in Indian Place-Names

- Index

- Index of Authors and Works Cited