This is a test

- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book, first published in 1965, illustrates the world of management in the airline industry. It examines the external relations with customers, government, investors, suppliers and competitors, as well as internal relations within the business such as organization and industrial relations.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Airline Management by W.S. Barry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

External Relations of Management

Chapter I

Relations with Customers, Passengers, Shippers and Charterers

Introduction

There is not any brand new idea on the dealings between airline managers and their customers that needs to be taught. As Dr Johnson said, 'People need to be reminded more often than they need to be instructed.' In describing and analysing the characteristics of passengers, shippers and charterers, this chapter does no more than sum up what every good manager knows already. Its real job is to bring managers back to the old simple principles which so many of us are too busy to see.

Every manager needs to remind himself, again and again, that customers matter most. Whether he be engaged on an engineering problem, or a flying problem or a finance problem, the customer is the only sure point of final reference. Every manager should be continually asking himself questions like these. How will what I am doing affect our customers? Am I making things better or worse for customers?

These questions cannot be answered properly unless managers take themselves back, time after time, from their specialist activities, to a consideration of people. They must learn to understand the human nature of the beings, whom it is their main purpose to serve.

The distinction between ‘customers’ and ‘consumers’

Some managers believe that it is useful to distinguish between customers and consumers. The former are considered to be people who actually make the decision to use a particular airline. They are supposed to include travel agents, business houses, 'other' airlines, and at the end of the list, the man in the street. Only a small percentage of airline services are bought directly from the airlines who fly them.

It may be useful to classify the travel manager of a company as a customer, and the company representatives who actually do the travelling as consumers. But it is less useful to classify travel agents, and 'other' airlines as customers acting on behalf of consumers. The travel manager is a person who decides to pay out money to a particular airline. Agents cannot decide to pay out money, unless instructed by principals. This does not mean that the influence they exercise over the choice of their principals is unimportant, but that principals have a freedom of choice that remains important. The distinction between 'customers' and 'consumers' is useful only if it clearly separates those with power to choose from those who cannot.

Airline ‘customers’ and ‘traffic’

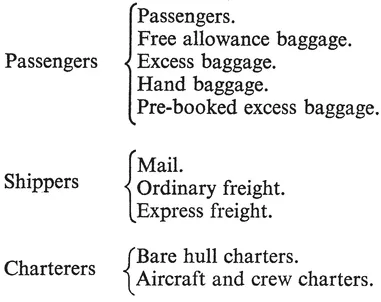

- (a) Airline customers may be classified as:

- Passengers.

- Shippers.

- Charterers.

- (b) The traffic they generate may be summarised as follows:

Various ‘classes’ of passenger travel

Airlines have, like rail and sea carriers, differentiated conditions of passenger carriage, to produce separate markets, based on the secondary intention of travellers. The names commonly applied to the various conditions are: 'first class', 'tourist', 'economy' and even 'austerity'.

Airlines have to judge carefully the value of these divisions of the passenger market. If they do not represent abiding features of demand, but rather artificially stimulated and temporary phenomena, then they may be more nuisance than they are worth.

Airlines are justified economically in differentiating markets if:

- (a) Some passengers are persuaded to leave a less profitable, and enter a more profitable, market, and/or

- (b) Some people are persuaded to fly, who would not otherwise have flown.

The 'extras-to-carriage' that are used to distinguish the various classes of passenger transport are:

- (a) Separate compartments.

- (b) More leg-room and elbow-room.

- (c) Better food, and free drinks.

- (d) A higher proportion of cabin attendants to each passenger.

If the technical difficulties in providing different classes of travel are considerable, they must be offset against additional revenue earned. Hitherto, airline organisations have not been sufficiently flexible to adjust rapidly to short term changes in demand for various classes. Managements have had to plan seating configurations that were best on average, knowing that at times this would cause loss of revenue. A particular seating configuration irrevocably built into an aircraft is too serious a risk, so most airlines have demanded some 'flexibility' in the design of their aircraft interiors. This may involve movable bulkheads and interchangeable seats. A promising development came in 1964 when be BEA introduced in its Trident aircraft, passenger seats that are convertible in a few minutes from first to tourist class standards.

Demand for various classes of travel can be controlled within certain limits by altering tariffs.

Government intervention in management-customer relations

If governments provide some of the services associated with air transport they may influence the relations between management and their customers, for better or for worse. This is particularly the case with passengers. Their memory of a journey may be coloured by impressions of treatment at an airport. That treatment might have been at the hands of government and not airline employees. Many passengers fail to discriminate between them, and blame the carrier for everything that goes wrong.

Managements have to answer to their customers for the mistakes of government employees. Customers cannot be expected to regard government employees, providing airport services, as other than agents of the airlines. The only remedy for airline managements is to complain to the government for their employees' shortcomings. These complaints do not, however, carry much weight with the government because the airlines cannot apply the normal sanction of dismissing the agent who does not carry out his principal's wishes.

Governments also affect the relations between airlines and their customers to some extent by the way they treat people at customs and immigration examinations. Once again it is wise for airlines to accept responsibility for these inconveniences, and to keep exerting pressure on the authorities to mend their ways.

The preference of passengers for particular types of aircraft

Passengers' likings for particular types of aircraft are strong enough to attract them away from the services of one airline and towards those of another. There is evidence that on certain routes, many passengers transfer as each new type of aircraft arrives. What lies behind these preferences is obscure and probably irrational. For example, the fastest aircraft has a strong pull, even though its advantage in speed cannot be fully realised because of the time spent on embarkation and disembarkation.

The engine noise heard in the passenger cabin has some bearing on likes and dislikes. It is probably an unwelcome reminder for passengers that their lives depend upon the engines. It is interesting that the noise of engines has been replaced by music in some of the quietest aircraft. Vibration also causes uneasiness, and so does turbulence. Cabin pressurisation was a great advance in standard of comfort that created a gulf between pressurised and unpressurised aircraft.

There are grounds for believing that the look of an aircraft, whether it be streamlined or ungainly, influences traffic. Passengers also seem to notice technical details, like rate of climb. But whatever list we made would fail to answer the question. Why do some aircraft 'catch on' and others not? Why did the Comet prove so popular that it was able to overcome the disadvantages of high operating costs? The lesson has now been well learnt. Airline equipment is not just a matter of production costs, but also of passenger-appeal.

The order of passenger satisfactions

Doubt is not confined to passengers' reactions to the type of aircraft. Very few surveys of passenger satisfactions have been made. The few that have been completed covered too small a sample to be conclusive. They suggest, however, that the subject would repay study.

One of the soundest surveys was interesting not only because it confirmed the theory that passengers first and foremost want to arrive at their destinations on time, but also because it did not support beliefs currently held on the importance of such extra-to-carriage services as catering, cheap cigarettes, and so on. The last word will probably never be said on passenger preferences because the means of investigating lack precision.

But airlines must go on searching for the answer because the various items of satisfaction cannot be reconciled. For example, it is sometimes impossible to get an aircraft away on time and complete the catering services, so it is a question of doing one or the other.

The order of satisfactions may differ from one route to another. On a holiday route incidental services may be more important than punctuality. On a business route punctuality and reliability may be all that matters. The order of satisfactions may also alter according to the time of a flight. Early morning and late night preferences may differ from those of mid-day. The order may also differ according to seasons and to whether passengers are catching connections.

If managements do not appreciate passengers' views, then money may be spent in an order of priority that does not coincide with that of the customer.

Customer complaints

When customers complain it is usually to the management. The two-way flow, of complaints and answers, forms a valuable link between management and customers. Apart from a small minority whom it is impossible to please, those who complain are worth listening to. Complaints come from the articulate, from those with the courage of their convictions, and from those who lead opinion. For this reason airlines do well to pay heed to them. Management can often create more goodwill by dealing sympathetically with aggrieved passengers, than by operating a number of uneventful flights.

Apart from the opportunities that complaints afford for creating personal relations, they also provide information on how to improve service, and hence to improve the general reputation of the airline. If complaints are analysed and classified over a period they form a valuable means of discerning trends in the quality of various services. Individual complaints taken in isolation can easily mislead the investigator as to their causes. But if complaints are dealt with in aggregate, it is possible to eliminate the occasional accident and to concentrate attention on the recurring issues.

Many complaints concern damage to or loss of personal baggage. Then they are accompanied by claims for compensation. One of the ways of damaging an airline's reputation is to treat complaints and claims as if they were unrelated. The natural suspicion, with which claims are regarded, must not be allowed to destroy the sympathy that is necessary in dealing with a complaint. In dealing with every claimant it is wise to treat him also as a complainant.

Aspects of service that customers comment on

The following are the aspects of service that evoke most comment from customers:

- Standard and extent of advertising.

- Treatment received from airline's agents.

- The way baggage is handled (delays, losses, damage, etc.).

- Excess charges for baggage.

- Left luggage facilities.

- Airport catering facilities.

- Dealings with customs, immigration and health authorities.

- Flight delays, diversions and cancellations.

- Consequences of missing a flight.

- Charges made for various services.

- Information services (enquiry points and signposts).

- Motor transport associated with the airport.

- Manner of embarkation and disembarkation.

- Treatment of special passengers.

- Arrangements for catching connecting flights.

- Failures to obtain seats on aircraft.

- Aircraft interior appurtenances (public address system, heating, ventilation, noise, vibration, pressurisation, lighting, seating, luggage stowage and toilets).

- Noticeable features of take-off, cli...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- SUMMARY OF THE CONTENTS OF EACH CHAPTER

- PART I EXTERNAL RELATIONS OF MANAGEMENT

- PART II INTERNAL RELATIONS OF MANAGEMENT

- PART III THE INDIVIDUAL MANAGER

- APPENDIX I—NEW THINKING IN MANAGEMENT

- APPENDIX II—THE ORGANISATION STRUCTURE OF AMERICAN AIRLINES

- INDEX