History and preservation

In 1980, when David Watkin observed that it was becoming “increasingly clear that two of the most important and persistent motives which lie behind the production of architectural history are the practice and the preservation of architecture”,2 he was identifying – not without some criticism – the contemporary role of architectural historians in the education and preservation of memory. We can use his comment as a starting point when examining controversial issues regarding the relationship between history and preservation, focusing on protection and its role as interface between academia and those bodies charged with the protection of architectural heritage. Although this position crosses into the field of instrumentalized architectural historiography, it remains closely linked to the relationship between journalism and history, as was first suggested by Bruno Zevi in his renowned journal L’Architettura. Cronache e storia, first published in 1955.3

This essay aims to put the previously mentioned relationship to the test in the place where there may be greatest tension: when history converges with the present. In other words, we intend to examine reciprocal cultural and legislative approaches with regard to architectural production from just before the Conradian “shadow line”. This will bring us to define as “contemporary” that which is not “historic”, in accordance with commonly used guidelines.

Great awareness of the processes of globalization that affect architecture has been shown in the analysis of the criteria and of the role of protection. These processes have generated a dialogue, between very differing realities, on an increasingly common theme, as we shall see later. This dialogue has become more and more vibrant, thanks to the potential of networking, which has also brought about a series of useful and well-known advantages for scientific research: speed in communication; easier access to institutional platforms; easy consultation of a growing number of regulations, both past and present; opportunity – unthinkable ten years ago – to navigate far afield with the aid of ever-more advanced and constantly updated web applications; the diversification and continuous increase of online documentary and bibliographical sources; the exponential multiplication of historical and contemporary iconographic sources, previously only available via a small number of standard publications, which

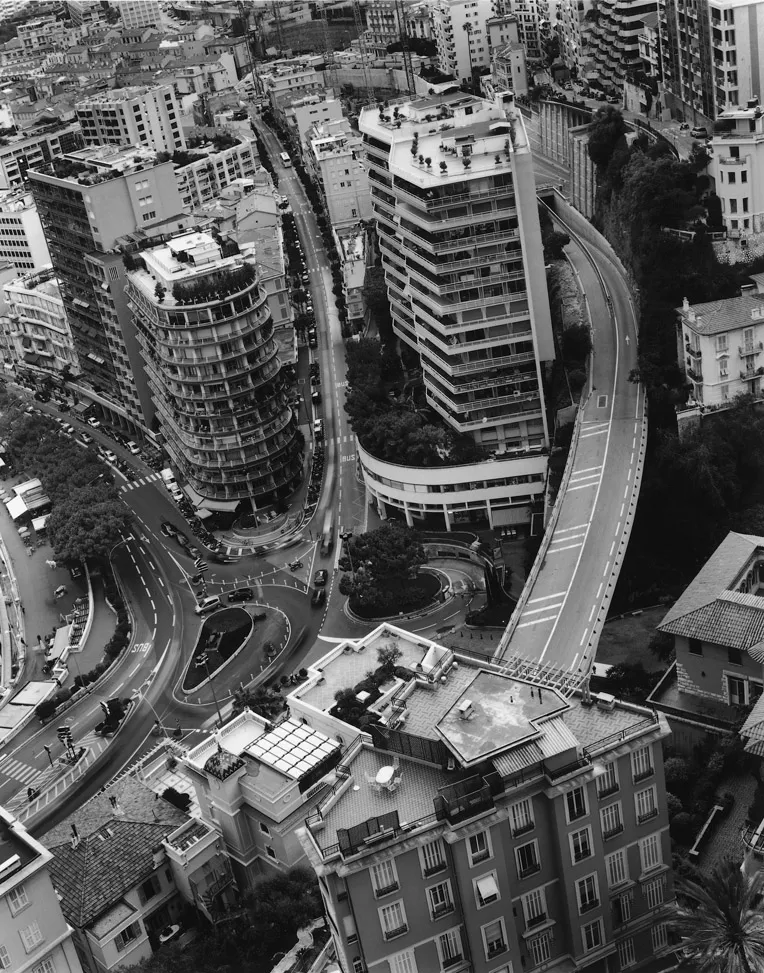

Figure 1.1 Gabriele Basilico, Monte-Carlo 05-A12-137, 2005. Collection Nouveau Musée National de Monaco, No. 2005.20.1. Gift of the Association des Amis du NMNM © Gabriele Basilico/NMNM /ADAGP, Paris 2016

have become art photography favourites; and the numerous databases that are freely available and easy to share.4 Rather, architectural photography is currently one of the main urban iconographical instruments to observe the transformation of the contemporary landscape, new urban forms and identities of cities and metropoles. Meanwhile, paintings with the same subject are less frequent, but we can find many interesting artists devoted to the urban representation from the second half of the twentieth century until today.

These research tools, along with architectural historians’ traditional working methods, have obviously opened up new critical perspectives. It is bringing new dimensions to the ambivalent geographies of architecture that offer fresh opportunities for re-thinking the borders of architectural history in a globalized, transcultural context.5

Heritage and globalization

We used one of the questions that were put to authors in the first part of the book – is there a time limit for the inclusion of architecture in your national cultural heritage? – in order to identify the rules, mandatory limits and thresholds beyond which institutions may not ordinarily recognize the value of a building and ensure the preservation of its authenticity. In other words, the study was aimed at whatever method lies at the heart of the process of monumentalization, not only of the Modern, but above all, of the Contemporary. The inclusion of the most recent works in the national inventories, lists or records ensures the ongoing update of that country’s cultural identities. Thus, there is the implicit proof of the existence of a deliberate commemorative value, Alois Riegl’s third category, forming the obvious transition to present-day values: an eternally present theme which requires that architecture be protected from human destruction.6

The history of international architectural heritage preservation has been the subject of numerous studies, with detailed examples covering the most recent experiences of restoration and comparative studies of administrative policies,7 but without going into greater detail of twentieth-century architectural issues. Only recently several scholars have raised the need to review the parameters of intervention on modern architecture in relation to natural instances of growth, innovation and development.8 Reassessment of the Modern Movement and Modernism is evident in renewed enthusiasm for the protection of this heritage, as shown by the phenomenal growth of Docomomo International, a non-profit organization founded in 1988, which now has 69 chapters worldwide; the recent inclusion of modern complexes in UNESCO’s World Heritage List; the special initiative Modernism at Risk, by the World Monuments Fund, a private non-profit organization founded in 1965 and today one of the largest in the world, not to mention numerous other active institutions and cultural realities the world over.

This phenomenon can only be contextualized in the extraordinary acceleration that the internationalization and globalization of world-built heritage has undergone, rooted, amongst others, in the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World’s Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972), which was followed by the European Charter of the Architectural Heritage (1975).9 At the same time, the dissenting culture of those years looked favourably on the concept of nomadism as a future existential condition, free from time and space, and encouraged the early development of this globalization of architecture,10 which is reflected in Radical Architecture, and also in contemporary historiographical contributions.11 This opened a new critical trend, which over time has been purified of its most ideological positions.12

In recent years, the cultural heritage of twentieth-century architecture, which had tended towards an anti-historical and self-referencing interpretation of modern architecture and a paradigmatic position within the Western architectural tradition,13 has in fact been challenged by a series of new critical contributions, coming from outside the usual geographical boundaries of historiography. This breach was opened by the birth of the category of “Critical Regionalism”14 that allowed the emergence from the shadow of a number of architects, both emigrés abroad and at home, in countries that had not enjoyed significant historiography for a long time. Given the impossibility of summarizing here recent historiographies from the critical debate on contemporary architecture,15 the reader is referred to recent books which explore the complex relationship between modernism, modernity and modernization and their entanglements with colonialism and post-colonialism, and nationalism development, globalization and regionalism, drawing from interdisciplinary theories. They start from the generally accepted consideration that the canonical history of modern architecture is primarily a narrative based on certain master architects, major movements and exemplary buildings in Europe and North America. Sibel Bozdogan even goes so far as to say that the study of non-Western modern architecture was, until about 20 years ago, “doubly marginalized”,16 both by historians of modern architecture and by local specialists and scholars. With the previously mentioned temporal expansion there came also the geographical enlargement of the scope of the history of modern architecture, which moved from its traditional centres to include parts of Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America as sites of proliferation of modern architecture in the mid-twentieth century.17

The topicality of the current debate tends to revalue a past which in some respects is still too recent, particularly in the Western world, where historiographies have for some time reached greater scientific maturity.18 Indeed, especially in the non-Western world, the Modern Movement has prevailed to such a large extent over post–World War II works that it has itself become fully synonymous with twentieth-century architecture. The great authorities of modern architecture have overshadowed later works, and the latter have been generally unable to establish themselves in the public eye, despite achieving clear recognition among specialists. This condition is mirrored by some woefully inadequate cultural and regulatory limits when compared to architecture’s new geography and even history.

The numerous cataloguing and research programs in progress bear out the need to re-examine time limits from within the new cultural-historical context.19 This has been theorized in different times and ways by art historians or, as often happens, within different specialist fields, such as analytic aesthetics, or post-criticalism, or by architectural practitioners themselves, pre-empting and directing attention onto issues and subjects ignored by historians of the time.20 This constitutes a legacy of the most recent past which, in accordance with artistic and intellectual tradition, was developed at its very inception and which has continued without interruption. It continues to yield a veritable wealth of significant and historically interesting literary and iconographic material, thereby increasing collective cultural values.

Figure 1.2 Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, University of Ibadan, 1949–1960

Time rules

In case we feel tempted to take for granted the current boundaries of contemporary architecture, they do, however, appear quite discretionary when measured against the various criteria established by law for the designation of a work as a heritage. This tendency is even stronger when it comes to dealing with the notion of time and, more specifically, of contemporaneity. It is easy to understand how the apparently transparent term “Contemporary” is actually far from being passive. The picture that emerges reveals a number of differences, as shown in the attached synoptic table. The way it has been drafted queries the recognition of the primacy of historiography over regulations, of time over history, of the work over its function and of public ownership over private property. This multitudinous variety of current time rules for architectural protection reveals, to all intents and purposes, how precarious they are and how difficult a unified reading might be.

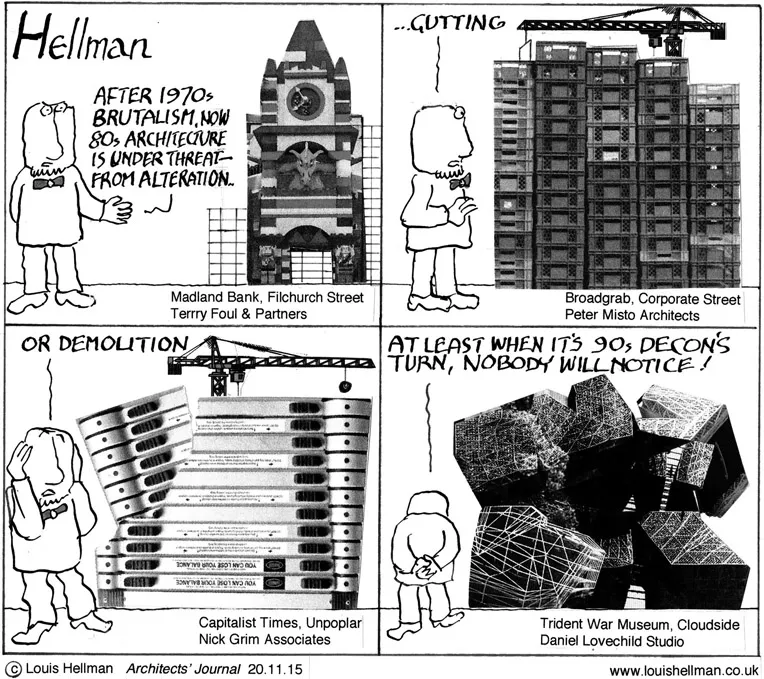

Figure 1.3 Louis Hellman, Architect’s Journal, 20.11.15

The first dichotomy is between historiographies and the law, that is, the extent to which historiographical criteria are binding upon the action of protection, on the eventual critical success of a piece of work, on the eventual completion of the life cycle of an architectural movement and sometimes on the authors themselves. Time limits are either associated with a time indicated in an absolute quantitative value in relation to the well-known definition of a “generation” (25 years) and commonly expressed as the “Fifty Years Rule”,21 or they may be associated with the history or the date of an event that has made a significant contribution to the community, province or nation. It is also possible to distinguish another cultural dichotomy: on the one hand the protection of heritage as an asset, so what is safeguarded is its physicality, and on the other hand a protection that respects the identity of the asset and the continuity of its function. Finally, we have two other opposing approaches: the analytical type, in which protection is bound exclusively to the work or even to just a part of it, and the other, holistic, type, in which the conservation of the architecture is related to reco...