While law is generally limited by national boundaries, economics is not. Moreover, the discipline of economics has played a major role in the development of the competition laws of the United States, Canada, and—albeit to a lesser extent—the European Union.3 Accordingly, it is helpful to consider the economic theories of monopolization as well as the manner in which the discipline of economics can inform the application of monopolization laws in different countries, even though the laws of these countries may not be consistently grounded in, or based solely upon, economic principles.

Economics informs the study of monopolization law in at least two ways. First, welfare economics permits the identification of the economic harms and benefits as well as the re-distributional effects of monopolization.4 Second, industrial organization economics and game theory provide insight into understanding the ability and incentives of a dominant firm to engage in anticompetitive exclusionary conduct, which can inform enforcement and policy decisions.5

A. THE ECONOMICS OF MONOPOLIZATION: A WELFARE PERSPECTIVE

From an economic welfare perspective, competition is generally desirable because it can lead to at least three economic effects:6 (1) it can facilitate the allocation of resources to their most valued use (i.e., it promotes allocative efficiency); (2) it can cause firms to react to competitive pressure by attempting to reduce their costs (i.e., it promotes productive efficiency or reduces X-inefficiency); and (3) it can cause firms to introduce new products and new ways of producing existing products (i.e., it promotes innovative or dynamic efficiency), which, through the process of competitive diffusion,7 can place intense pressure on other firms to do the same. All of this generally leads to benefits and the creation of wealth for society and for its economic constituents (e.g., consumers, firms, etc.).

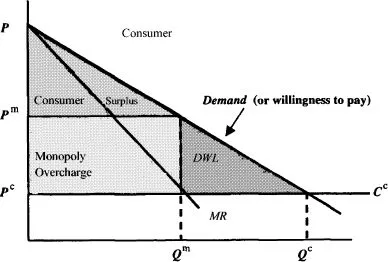

However, these beneficial economic effects can be prevented by the exercise of market power8 in several ways, depending in part on the source and nature of the market power. First, a reduction of output and increase in price above some benchmark level (often called classical market power) results in allocative inefficiency or a deadweight loss (DWL), as can be seen below in Figure 1:

Under competitive conditions, the socially optimal quantity of production, Qc, occurs where the marginal cost of production, Cc, equals the marginal benefit of consumption. The competitive price is assumed to equal the marginal cost of production. As shown in Figure 1, the difference between total surplus under monopoly and competition is called deadweight loss. It represents an opportunity cost of forgone consumption to society. By not producing units of output between Qm and Qc, society forgoes consumer surplus in an amount equal to the deadweight loss or, in non-economic terms, consumers purchase things they are less satisfied with compared to the monopolized product.9

A second effect of the exercise of market power is a notional redistributive effect.10 In the absence of monopoly pricing, the amount representing the monopoly overcharge would go to consumers. Monopolistic pricing means those consumers that are still willing to purchase goods at the higher price suffer a “notional” transfer of their wealth (the difference between the competitive price and the monopoly price) to the monopolist.

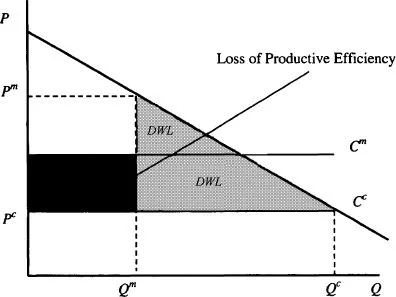

A third effect of the exercise of market power involves its impact on productive efficiency (or X-inefficiency) and innovation or dynamic efficiency. For example, the exercise of market power may result in managerial slack, with a result that a firm may not operate at lowest cost–both now and into the future. As has been pointed out elsewhere, this is an additional social cost of market power because a firm’s costs rise as its employees perceive that maximum effort to compete is not necessary.11

The X-inefficiency costs associated with monopoly can be seen in Figure 2. The effect of organizational slack is to increase costs from Cc to Cm. In Figure 2, the lost surplus from monopolization then consists of the lighter shaded area (the deadweight loss associated with the monopoly output Qm) and the darker shaded area (loss of productive efficiency due to wasted inputs from the failure of the monopolist to minimize costs).12

Moreover, to the extent that rivals’ costs are raised, exclusionary market power can cause the same effect. Rivals may then produce at higher cost resulting in further losses of productive efficiency and corresponding harm to social welfare. In addition, harm from exclusionary market power may also result from socially wasteful rent-seeking behavior. Rent-seeking results in additional social costs from the efforts a firm will expend to acquire and/or maintain market power.13 Another way of viewing this is in terms of the cost that a firm is willing to incur to purchase exclusionary rights.14

Rent-seeking behavior carries social cost because the resources utilized by firms for this purpose are wasted in an economic sense. These expenditures produce only monopoly profits instead of products for consumption. In this sense, a measure of the maximum of the productive resources wasted on rent-seeking activities is the value of the monopoly profits sought.15

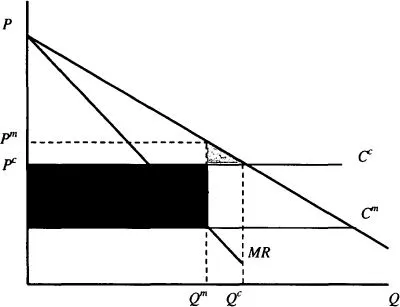

Conduct which confers market power is not, however, always harmful. In many instances, conduct or arrangements that also result in the exercise of market power often generate efficiencies (such as economies of scale, preventing free-riding, innovation efficiencies, etc.) that can offset economic harms resulting from the exercise of that market power. For example, in the context of mergers, one line of economics suggests that if a merger to monopoly results in a decrease in industry costs, these resource cost savings may compensate for increases in allocative inefficiency (i.e., deadweight loss).16 This can be seen in simplified form in Figure 3.

In Figure 3, costs under competitive conditions are denoted Cc. The cost curve for a monopolist is Cm. The move from competition to monopoly would increase total surplus by the darker shaded area less the lighter shaded area17 The light triangle is the lost consumer surplus associated with monopoly pricing. The darker rectangle represents the cost savings associated with the lower costs of the monopolist. As Figure 3 shows, it may not take very large cost savings to compensate for the allocative inefficiency caused by a merger. This approach, however, has not found favor with the agencies or the courts.18