So wrote Lady Grace Gethin, in her commonplace book of the 1690s, unaware that she would die before she reached the age of twenty one. Although her critique of death is a highly personal one, it serves to illustrate the more general view of personified Death in Early Modern England; an ever present danger, highly visible in comparison to its descendant in Modern England, and a source of concern that exercised the minds of a multitude of writers.

The Fear of Death: Pious Publications

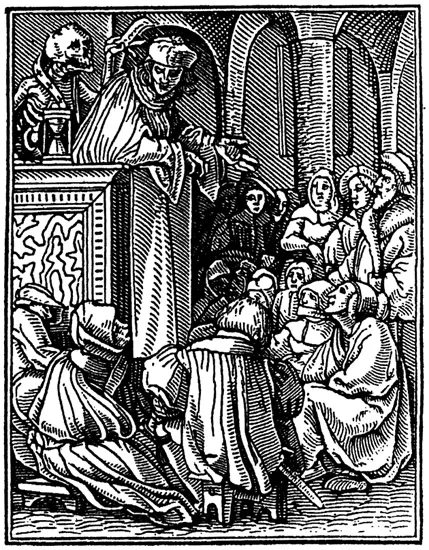

The general horror of death is reflected in the means by which Early Modern society sought publicly to cope with the fear, primarily through sermons on the subject, pious conduct books and religious tracts, poetry and, especially for the poor, the chapbooks and street ballads that were ‘the conduct books of the lower classes’.2 Of course, these publications were not produced simply to ameliorate the fear of death; they were also used to exploit the natural anxiety over death and dying, at times employing ‘an element of shock tactics in the deliberate evocation of the horrors of death’ in order to ensure religious observance and social compliance.3 Certaine Sermons or Homilies appoynted to be read in Churches is a collection of sermons originally published in 1562, although still being produced in 1633, and legally required to be used on a weekly basis in churches throughout England. ‘An Exhortation against the feare of death’ is one of the principal sermons of the collection, and demonstrates the perception of both the clerical and the secular authorities that the fear of death, and also of purgatory, needed to be curtailed, controlled and, if possible, utilized.4

The sermon echoes in both its structure and theological content earlier works, such as the sermons of the Franciscan preacher Bernardino of Sienna (1380–1444).5 The homily recognizes that the horror of death, which is superficially brought about by different concerns in differing social groups (the rich man fears the loss of his riches, the poor man, the pain of sickness), includes also the greater fear of the ‘second death’, that is, ‘an everlasting losse without remedy of the grace and favour of God’ (p. 59). By invoking the ever present fear of death, the sermon draws upon a rich vein of terror in society, which it then attempts to confront by reiterating the doctrine that

bodily death [is] a doore of entring into life, and therefore not so much dreadfull (if it be rightly considered) as it is comfortable; not a mischiefe; no enemy, but a friend; not a cruell tyrant, but a gentle guide leading us not to mortality, but to immortality… it [is to] be thankfully taken and accepted as GODS messenger (p. 61).6

There are plentiful examples of death in literature and popular culture as ‘a mischiefe’, an ‘enemy’ and a ‘cruell tyrant’, but the sermon writer tries to reverse this imagery by inducing the correct frame of mind, invoking the traditional trope of the life to which we cling as no more than a journey towards death. He refers to the writings of St Paul, where ‘the life in this world is resembled and likened to a pilgrimage in a strange countrey, farre from GOD, and that death, delivering us from our bodies, doth send us straight home into oure owne countrey’ (p. 62). The use of the term ‘delivering’ here is no coincidence; the links between childbirth and death are evident in several sources, death bringing forth a form of new life in God. The pain of death is, according to the sermon, simply ‘our Heavenly Fathers rod’ chastizing us for past sins, and death should be approached ‘with a quiet conscience in Christ, a firme hope, and assured trust in GODS mercy’ (pp. 64 and 68). It is this frame of mind, leading to a good death, for which it was hoped the recipients of the sermon would aim.

Sermons from the pulpit were supported by a plethora of pious conduct books on how to die well. Most of these books are dedicated to women, perhaps suggesting that they needed more help than men, or perhaps in recognition of their role as principal carers for the dying. However, the examples used in such books are almost invariably male, and the emphasis is upon the correct mental approach to death. In The Doctrine of Dying Well (1628), for example, the author likens dying to the smelting of gold: it looks destructive, but actually produces an enhanced spirituality; thus, ‘death unto the godly is nothing else but a sleepe, whereby we are refined and refreshed’.7 Those witnessing death are therefore not to fear the fact of mortality in themselves, but to see their own death in the speculum mortis and to realize that they have ‘greater cause to rejoyce than mourne, because they goe to be glorified with their heavenly father in heaven’ (p. 32).8 Shawe is happy to advocate exposure to the deaths of others in order that his readers may learn how to die well, and adds that ‘every grave and tombe be monuments to put us in minde of death’ (p. 34). Posthumous images of men and women, either in monumental statuary, or in written accounts of their lives and deaths, are also part of this process of exposure to death, thus reminding man of his mortality and helping in the preparation for a death well done.

This ever present awareness of death is reiterated in The Manner to dye well, an earlier godly conduct book of 1578, in which the author urges the reader ‘Never (to)

go thou to bedde with such a conscience, wherein thou fearest to dye’.9 He goes on to try, in verse form, to reconcile the reader to the physical aspects of dying by suggesting that a prolonged death is merely an indication that the soul is reluctant to leave the body before full reconciliation with God has been achieved:

Ten thousand griefs begin to paine,

the wicked Soule with woe,

When from the prison of the fleshe,

away it needes must goe.

It doth lament with streames of teares,

the vayne bestowed time,

Wherein it might ful leasurely,

repent each sinful crime

And bitterlie with scryching cryes,

it makes a rufull mone:

To see the time of strict revenge,

that drawes so hardlie on.

It seekes a whyle then to remaine,

in hope some mendes to make:

No sute maye then prevayle, but that

the fleshe it must forsake. (p. 10)

Such advice is in keeping with that given in other other similar works, such as The Rule and Exercises of Holy Dying (1651) by the prolific writer Jeremy Taylor. The author stresses the military rigour with which dying must be approached; the dying person is told to ‘proclayme thou open warre against al vyces, with a determinate wyll not to sinne, renewing oftentymes this holy battayle without ceassing (p. 15)’.10 Such military imagery could be taken up with enthusiasm by dying women, but, in most cases, it posed a peculiar problem for them, and will be discussed further in Chapter 2.

In addition to pious conduct books, there were also popular reminders of death in ballads and chapbooks, for example the ballad Deaths Dance, which was printed in 1631 and follows the popular tradition of the Dance of Death, developed in Europe towards the end of the fifteenth century and becoming both ‘one of the most haunting and most popular images’ of the Early Modern period and ‘one of the most important weapons in the armoury of anyone seeking to drive home the brevity of life, and the need to prepare for death while there was still time’.11 Deaths Dance combines the macabre and the comic in typical fashion and highlights a universal preoccupation with death. Sublimating this fear through the singing of ballads serves a similar function to the ‘comic relief’ aspects of a Shakespearean play: the comedy exists, but its piquancy relies upon its reflection of the underlying tragedy into which it intrudes. The popularity of ballads such as this, and the Dance of Death iconography as a whole, is reminiscent of the subject matter chosen for comedy, literature and popular art in any age, material that both faces and undermines the fears of a society.12

The final stanza of the ballad Deaths Dance makes clear the motivation behind its creation, reminding the reader that ‘Death hath promised to come, / and come he will indeed… Though he be blind and cannot see, / in earth he will bestow you’. The link between blind Death and blind Cupid is made clear in other publications, both being gods of chaos, blind to the state of those they take.13 The personified death in Deaths Dance shows himself to be more potent than any power in the land, able to ‘overrule them all’, spying out the rich and powerful, the cheerful and gossiping, putting ‘them all in feare’; ‘in the midst of life [they] are in death’.14 The ballad writer includes women as a distinct group within society, as had earlier writers. Indeed, some of the early Dances of Death (for example, Martial D’Auvergne’s fifteenth-century Danse macabre des femmes) had been comprised entirely of female subjects.15 The writer of Deaths Dance depicts women as trying to fight off the fear of death in their own way, as they ‘daily go so fine and brave / when they his face do view’. Here the idea of feminine beauty is dismissed as no more than a vain attempt to deny mortality, although in other more serious works physical beauty is replaced with the consolation of spiritual beauty as a means to fight off extinction in death. This theme is rehearsed repeatedly throughout the period.

Death was, naturally, a prevalent subject in private (or, at least, semi-private) writings of the time. Diarists, both male and female, report death as part of the everyday life around them and it is clear that death is a constant reminder to the diarists of their own mortality. Whilst many of their descriptions of dying are made palatable by reference to the clichés of a death well done, the physical horror of death cannot always be ignored. There is thus a dual aspect to the Early Modern view of death. People were urged by the clergy and pious writers to face death with heroism and acceptance (if not always outright enthusiasm), but were nevertheless unable to escape its unpleasant realities, made more fearsome by lack of medical knowledge.

In the poem ‘The Temple of Death’ (1672), written within the poetic genre that concerned itself with this subject matter, a realistic description of the horror of death, as understood by readers in their weaker moments, is offered. The work is included in an anonymous collection of poems published in 1672, and here the home of death is a ‘dreadful vale’ with ‘flocks of ill-presaging Birds’ and ‘Millions of graves’, in which the ‘springs of blood and thousand Rivers yield [and] pour forth groans’. The Temple of Death is ‘Old as the Universe which it commands’, and the subjects of that temple, all mankind, are ‘doomed to one common grave, / The young, the old, the Monarch and the Slave’.16 Thomas Flatman also captured the reality of the deathbed in the opening lines of his poem of 1674, ‘A Thought of Death’:

When on my sick bed I languish,

Full of sorrow, full of anguish,

Fainting, gasping, trembling, crying,

Panting, groaning, speechless, dying,

My soul just now about to take her flight

Into the regions of eternal night,

Oh tell me you

That have been long below,

What shall I do?17

The public image of death is thus that of both aggressor and placator, ravager of mankind and guide to God. Death as an aggressor is not always, as one might expect, a male figure; in ‘The Temple of Death’, for example, she is a goddess, a female figure waiting to put lovers out of their misery. Although a...