- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The focus of this book is on understanding and explaining the way that our increasingly networked world impacts on the legibility of cities; that is how we experience and inhabit urban space. It reflects on the nature of the spatial effects of the networked and mediated world; from mobile phones and satnavs to data centres and wifi nodes and discusses how these change the very nature of urban space. It proposes that netspaces are the spaces that emerge at the interchange between the built world and the space of the network. It aims to be a timely volume for both architectural, urban design and media practitioners in understanding and working with the fundamental changes in built space due to the ubiquity of networks and media. This book argues that there needs to be a much better understanding of how networks affect the way we inhabit urban space. The volume defines five characteristics of netspaces and defines in detail the way that the spatial form of the city is affected by changing practices of networked world. It draws on theoretical approaches and contextualises the discussion with empirical case studies to illustrate the changes taking place in urban space. This readable and engaging text will be a valuable resource for architects, urban designers, planners and sociologists for understanding how of networks and media are creating significant changes to urban space and the resulting implications for the design of cities.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture General1

Infrastructures

1.1 NETWORKED INFRASTRUCTURES

22@

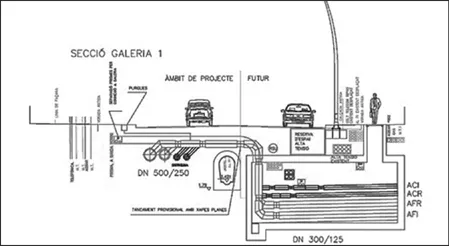

1.1 Cross section through Almogavers Street, 22@, Barcelona showing underground infrastructure ‘galleries’ (source: Barcelona City Council).

There were two rather unsettling things about my walk along Carrer de Tanger in the Poblenau district of Barcelona in autumn of 2013. Firstly, it was the fact the cills of the ground floor windows of the four storey historical brick building housing part of the UPF Communication Campus Poblenou were level with the street. So as you walked along and peered through the beautiful brick arched windows into the building inside you noticed that the floor level was about half a storey below. The second thing that made me curious was a large, anonymous box of a building, located directly opposite the busy University campus hub. It was obviously new, but the three storey high copper clad exterior appeared to have no entrance and no windows. The area I was exploring was to the east of central Barcelona; the neighbourhood of Poblenau. But since 2001, the district has been rebranded as 22@, a project that has converted 200 hectares of industrial land into a district for a ‘knowledge economy’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona, n.n.), and is often described as an example of a ‘smart city’ development. The reason for the strange sinking of the old brick-built factory buildings, now converted into high-tech media labs for the University? Part of the development involved the introduction of a new €180 million urban infrastructure which used the existing street system as a conduit for a converged power, heating, telecoms and waste disposal network. The existing street surface has literally been raised by two metres to accommodate 4.240 m of channels or galleries running beneath the road structure, comprising over 200 km of electricity cable, 700 km of telecommunications cable and 6.830 m gas pipeline (Ajuntament de Barcelona) (see Figure 1.1). According to the city ‘while each of the industry clusters are segregated into distinct areas containing residential areas and amenities, they are unified by centralised heating and air-conditioning, electricity distribution, waste disposal, telecommunications infrastructure, and smart traffic management systems’ (Leon, 2008, p. 238). So in 22@ there will be no sign of the ubiquitous men in yellow high-vis vests and a pneumatic drill, digging up the road yet again for a telecoms or power provider. Changing or updating or servicing the infrastructure of the neighbourhood is instead carried out by a workman walking into a gallery, so that new businesses can simply plugin to the system and capacity is controlled from a remote location, as people continue to walk the pavements above.

Which comes to the rather lonely looking copper clad box sitting in the middle of the street opposite? This turns out to be the power hub of the district; theTanger power plant, providing 26 MW for heating and 27 MW for cooling the seventy eight buildings in the 22@ district and linked up to a system spreading through the under street infrastructure. Powered by natural gas, and designed with the aim of reducing CO2 emissions by twenty two per cent the plant also guarantees a robust energy supply under peak conditions. And in another curious twist it turns out that the combustion gas from the boilers is exhausted by the historical chimney of the textile factory Can l’Aranyó, originally built in 1872. The massive brick tower, made redundant as the textile industry in Poblenau was superseded by Far East factories, has been brought back to life as a chimney which pumps out the gas from the plant powering the new economy; ICTs and education.

Interestingly not only did the design of the 22@ infrastructure create a new way to organise and connect the space of flows to the space of places, it also used this approach to create 114,000 m2 of new green space and 20,515 m bike lanes by opening up the existing dense urban grid into urban blocks and widening the sidewalks to seven meters. As a result, the fine grain of the urban street network has been replaced by larger, denser blocks that alter the sense of urban scale. The infrastructure of 22@ is in fact far from invisible or immaterial. The buildings need to be connected by vast swathes of power and fibre optic cables and installed in a way that allows for future change in occupancy and use of the buildings of the district. The power, telecommunications and transport infrastructure of a connected urban environment, such as 22@, create material changes in the structure and form of the urban fabric. If we remember that Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse created a vision of streets in the sky and fast moving traffic at ground level, in the connected city the traffic of data and energy is buried beneath the surface and the streets become rediscovered at ground level.

Invisible cities

What lies beneath the city is often overlooked. The city is framed by flows and channels; those of people, energy, money, vehicles and data. Urban places are linked by ‘movement channels of various kinds; doorways, street grids, transport networks’ (Mitchell, 1995, p. 117). Indeed the flow of information in, through and out of a city is a fundamental characteristic of urban life. These flows are enabled by infrastructure, which is usually understood as one of the key building blocks of urban life and structure. Indeed cities are the densest expressions of infrastructure, or more accurately a set of infrastructures, that sometimes work well, but are sometimes chaotic or ineffective. Urban infrastructure consists of various structures; buildings, pipes, roads, rail, bridges, tunnels and wires brought together in a connected framework. But this framework also has rules; ‘the software for the physical infrastructure, all the formal and informal rules for the operation of the systems’ (Herman and Ausubel, 1988, p. 1).The hardware and the software of infrastructure often remains beyond reach of the citizen in their everyday life; it tends to be dirty, technically complex, and concealed. In the midst of the last century Lewis Mumford was one of the first urban theorists to highlight the importance of this ‘invisible city’ (1961, pp. 563–567). Mumford described how ‘the new world in which we have begun to live is not merely open on the surface but also open internally … below the threshold of ordinary observation’ (1961, p. 563). The idea of the city as container was being supplanted by ‘new functions’ brought into being by what Mumford called ‘the functional grid; the framework of the invisible city’ which rather than reintegrating the essential components of the city instead has ‘tended to efface them’ (1961, pp. 564–565). The prime players in this transformation were the power and communications systems. According to Moss and Townsend: ‘the physical infrastructure that helped to shape earlier urban forms — the sea-port, the railroad, and the highway — is being superseded by a new network of optical fibres, Cisco routers, cellular antennas, and mobile telephones’ (1999, p. 46). Communication infrastructures in the twenty first century have become a critical part of how a city functions, but as infrastructure they also represent a fundamental change in how a city is organised and controlled. Communication is now being treated as part of the social and technological infrastructure of city life.

Networks and the city

The key problem to be addressed in this chapter is how the shift towards information and communications technologies (ICTs) changes the old idea of the integrated, centralised city that has an identifiable boundary and is separated from other cities by distance. Whilst simultaneously the flow of media exchanges happens without much physical evidence on the surface of the city, Graham and Marvin have highlighted how ‘rather than ending the domination of cities, these networks actually tend to erupt within the spatial order of the old city’ (1996, p. 71). Communications technologies, from the masts connecting mobile phone networks to the fibrous cables of the Internet, whilst crucial in supporting the mobility and flux, are also fixed networks that must be embedded in space.

Space of flows

In his classic essay on The Network Society, Manuel Castell introduced the idea of the ‘space of flows’ (Castells, 1996). He set out a strange new world, where he countered that the ‘the space of flows can be abstract in social, cultural, and historical terms … places are … condensations of human history, culture and matter’. They are no longer ‘places’, where ‘place’ is defined as ‘a locale whose form and meaning are self-contained within the boundaries of physical contiguity’ (Castells, 1996, p. 423). So Castells sets up a scenario that challenges the long-held privileged status of Cartesian geometry, the map, and the matrix or grid. Whether New York’s famous grid street system, or the centralised street pattern of European market towns, these were being replaced by a global network infrastructure, rendering the space of places irrelevant. Instead,’infrastructural links and connectors, as well as information exchanges and thresholds, become the dominant metaphors to examine the boundless extension of the regional city’(Boyer, 1999, p. 75). According to Graham and Marvin, the rise of globalisation ‘undermines the notion of infrastructure networks as binding and connecting territorially cohesive urban space’s … it forces us to think about how space and scale are being refashioned in new ways that we can literally see crystallising before us in the changing configurations of infrastructure networks and the landscapes of urban spaces all around us’ (2001, p. 16). Castells concept of the space of flows essentially denies the spatial experience, and concludes that as we occupy global network infrastructures we become simply mediators of information pulsing through the network. Graham highlights the embedded-ness of these space of flows in the space of places so that ‘the urban world connected by Gate’s technologies string out on the wire is not disconnected, abstract, inhuman; it is bound in the places and times of actual lives, into human existences that are as connected, sensuous and personal as they ever have been’ (Cosgrove, 1996, p. 1495). This became visible in the Poblenau district of Barcelona, now rebranded as 22@, with attempts to rename many of the existing urban spaces to reflect the new city structure. Some street plans showed roads that had, in fact, been lost because of the ‘blocks’ created by the densification of urban structure around various nodes of activity. Similarly the flow of people, previously to the textile factories, has shifted to new entrances and times as the students, IT workers and tourists of the knowledge economy flow in and out of the gateways. Meanwhile, an infrastructural building such as the Tanger power centre, which is a clear physical building within the street, is treated as an invisible entity. These are still meaningful places to both those who worked there, who visited them and those that linked in from global locations. But the flow of cables beneath the flow of people on the street above connected these places to a set of distant places that had as much meaning as those of the immediate urban fabric.

Aims

This chapter aims to explore the many different ways in which digital networks affect the structure of the city. It starts by opening up the concept of the network society, introduced by Castells (Castells, 1996), and discussing this in relation to a range of other readings and also introduces the terms ‘meshworks’ and ‘assemblages’ to consider more multi-layered and social perspectives on network infrastructures. An alternative reading of infrastructure through the concepts of assemblages and meshworks sees network infrastructure, not as invisible and placeless, but as embedded and interwoven with patterns of movement, energy and waste. It is important to remember that current digital infrastructures have not emerged from nothing, but are also part of a lineage that goes back to telegraph and telephone infrastructures. These wired networks have been shown to have had an effect on the spatial organisation of the city, shifting the organisation of urban spaces from centralised to networked and decentralised frameworks. More recent developments in the expansion of our digital infrastructure have caused a series of problematic conditions; firstly the invisibility of these infrastructures which has implications for the visual structure of cities, secondly, the black boxing, and thus de-socialising of these infrastructures, and thirdly the increasing shift of infrastructures into the sky and air and away from integration with existing built structures. These conditions are explored in more detail in thefinal section of the chapter where I look at the physical infrastructure of the Internet; data centers; which are where the data of the network is transferred and stored. The study of data centers shows that networked infrastructures are not only invisible and black boxed, but increasingly highly reliant on energy infrastructures. As such they pose important challenges for how we consider networked infrastructure as part of the spatial organisation of the city, and also open up important questions about the energy resilience of our increasing reliance on these infrastructures for many of our internet-driven everyday activities and urban processes.

1.2 MESHWORKS AND ASSEMBLAGES

Gaps in the network

Network theory, which addresses the widespread dispersal of digital information and communication technologies, of which mobile communication and the mobile Internet are the latest incarnation, has been considered by scholars as one of the central components of networked urbanism today (Castells, 1996); (Crang and Graham, 2007); (Graham and Marvin, 1996); (Graham and Marvin, 2001); (Mitchell, 1995) and (Shepard, 2011). Network theory of the nineties provided a valuable path through which to start to navigate and make sense of the interlinked global and local changes occurring in cities. However it also oversimplifies a much more complex set of inter-related flows and channels that are not limited to data, money, energy, water and vehicles, but also by their very nature include people, as well as the by-products of global connectivity such as rubbish and waste. Latour and Hermant point out that by paying attention to the material flows in and through infrastructures, you can appreciate more clearly how a city works. They argue that if you ‘study a city and neglect its sewers and power supplies (as many have), and you miss essential aspects of distributional justice and planning power’ (Latour and Hermant, 2004). Star argues that we can address this challenge by looking at the manifestation of networks at an everyday level, and through the way that they are standardised and categorised within existing frameworks. She contends that ‘Perhaps if we stopped thinking of computers as information highways and began to think of them more modestly as symbolic sewers this realm would open up a bit’ (Star, 1999, p. 379). To do this she argues that we need to look at it within its cultural and social context, just as ‘the cook considers the water system as working infrastructure integral to making dinner. For the city planner, or the plumber, it is a variable in a complex planning process or a target for repair: “Analytically, infrastructure appears only as a relational property, not as a thing stripped of use”‘ (Star and Ruhleder, 1996, p. 113; Star, 1999, p. 380). This underlies a fundamental problem with the way infrastructure is applied; ‘infrastructure networks are thus widely assumed to be integrators of urban spaces’ (Graham and Marvin, 2001, p. 8). But if we start to address them as complex, messy, incomplete and ‘knotted’ rather than sleek, impenetrable fibres, cables and pipes then this opens up a more authentic reading of the structures that weave through our urban life.

Through Actor NetworkTheory (ANT) Latour, drawing on original work by Law, introduces a more stratified understanding of this condition, by pointing out that ‘to say that something is a network is about as appealing as to say that someone will, from now on, eat only peas and green beans, or that you are condemned to reside in airport corridors: great for traveling, commuting, and connecting, but not to live. Visually, there is something deeply wrong in the way we represent networks, since we are never able to use them to draw enclosed and habitable spaces and envelopes’ (Latour, 2011, p. 800). Thus ANT sees networks not as obliterating spatial relations and processes, but reconfiguring them ‘involves relational assemblies linking technological networks, space and place, and the space and place-based users (and nonusers) of such networks (1993: 120). But one of the challenges of ANT is that to Latour, such technological networks are comprised of specific places ‘aligned by a series of branchings that cross other places and require other bra...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Infrastructures

- 2 Places

- 3 Boundaries

- 4 Publics

- 5 Times

- 6 Things

- 7 Future Challenges

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Netspaces by Katharine S. Willis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.