![]()

PART I

Growing Interest in Greening: 1920–1939

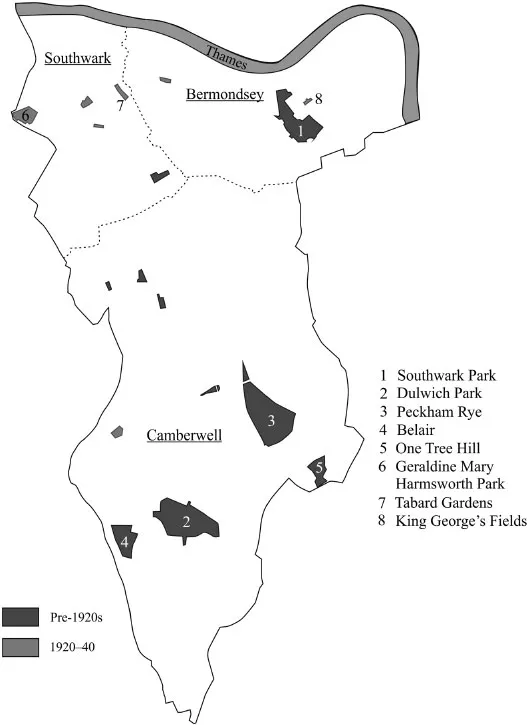

Figure 1.1 Public green space in Bermondsey, Southwark and Camberwell, 1920–39 (not every public green space is marked)

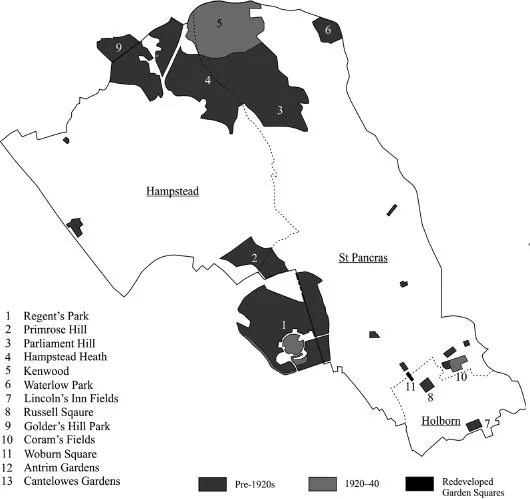

Figure 1.2 Public green space in Hampstead, Holborn and St Pancras, 1920–39 (not every public green space is marked)

![]()

Chapter 1

Provision of Public Green Space in Inter-War London

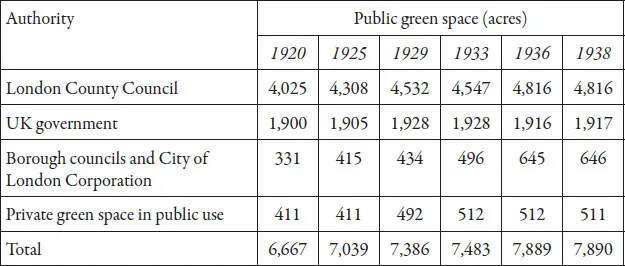

In the inter-war period, there was a widespread interest in the provision of new green space across the UK. In London, various agents succeeded in increasing the acreage of public green space from 6,667 acres to 7,890 acres between 1920 and 1938 (Table 1.1), in order to enhance physical recreation and outdoor leisure. In general, the UK government’s role in creating new green space in London remained permissive. Private landowners played a crucial role in providing sites to the municipal authorities, because the municipal authorities possessed limited legal and financial powers to create new public green space until the 1930s. With slum clearances, they began to improve the deplorable housing conditions in the city and to create new green spaces such as gardens and playgrounds from surplus housing land. The LCC, as the regional authority, concentrated on acquiring larger regional green spaces leaving the borough councils to create smaller local ones. The acreage open to the public in London’s royal parks grew because of a different policy: the termination of leased private enclosures. The 1920s were therefore an important period when many important polices concerning the greening of the city took shape and the provision of new green space became municipalised.

During the 1920s town planning emerged as a method for the municipal authorities as well as the government to control and restrain the growth of cities, especially London.1 To achieve this aim, many areas within the County of London and some inner suburbs needed comprehensive improvement to discourage the exodus of Londoners, leading the LCC to focus its housing policy on the city itself instead of the suburbs. Notwithstanding the emphasis given to town planning, the first town plans concentrated on preserving existing green spaces instead of providing for the creation of new ones. Thus, new green spaces were in most cases unplanned and sporadic, being based more on opportunity than on a coherent policy. This chapter will analyse why new green spaces were created and who was active in providing them; how slum clearances offered an opportunity for the municipal authorities to construct new green spaces and how that reflected their increasing power over the development of London; and finally how the loss of green space compared with its continued provision.

Table 1.1 Public green space in London by authority, 1920–38

Source: London County Council, London Statistics, vol. 26: 1915–1920 (London: LCC, 1921), 163; id., London Statistics, vol. 31: 1925–1926 (London: LCC, 1927), 136; id., London Statistics, vol. 34: 1928–1930 (London: LCC, 1931), 157; id., London Statistics, vol. 36: 1931–1932 (London: LCC, 1933), 162; id., London Statistics, vol. 38: 1933–1934 (London: LCC, 1935), 166; id. London Statistics, vol. 39: 1934–1936 (London: LCC, 1937), 185; id., London Statistics, vol. 41: 1936–1938 (London: LCC, 1939), 188.

New Interest in Greening the City

In the inter-war years interest in creating new public green space was generated by the perceived lack of such amenities due to continuous urban development and consequent loss of private green space.2 By the 1920s the built-up area of the city extended over most of the County of London apart from some areas in the south-east, notably Greenwich, Lewisham and Woolwich. The loss of green space, mainly private gardens, due to urban sprawl affected the outskirts of London and the Home Counties, although some private estates were converted into golf courses.3 As urban sprawl went uncontrolled, the built-up area of London doubled during the inter-war years:4 3,000 acres of, mainly private, green space were lost to development in the Greater London area between 1925 and 1933.5 However, the fact that the population in many London boroughs fell during these years, as residents moved out to the new suburbs, offered the municipal authorities an opportunity to redevelop their boroughs.6 In Southwark, the population fell by 39,100, and in St Pancras by nearly 32,000.7 Furthermore, widespread concern about the deplorable physical conditions of the working class generated a strong political movement for improvements in public health.8 A top-down centralised national policy on public health concentrated on the housing, nutrition and sanitation of the lower classes,9 promoting open-air activities and physical recreation.10 In fact, physical fitness was a new dimension in the policies aiming at general improvement of public health. The need to improve the physical fitness of young men was another reason for providing more public green space. David Reeder described the provision of playing fields in the inter-war period as ‘the leitmotif of planners in London’.11 At the national level, the promotion of physical recreation culminated in the Physical Training and Recreation Act of 1937, which empowered municipal authorities to create playing fields with land obtained through compulsory purchase.12 In contrast to the national policy, the role of London’s municipal authorities in providing new gardens and recreation grounds for physical recreation has been somewhat neglected.

At the local level, the emphasis of policies concerning the provision of new green space changed to promoting physical fitness rather than ‘open-air’.13 Politicians and municipal authorities, and in the case of the royal parks, civil servants of the Office of Works understood the beneficial effects of green space to concern physical recreation and the provision of approved and controllable outdoor leisure. The diminishing working hours of the working classes in particular and their increased participation in local government enabled them to influence the policies of local authorities.14 In the mid-1920s physical recreation surfaced in discussions about the provision of new green space in London. A report by the Ministry of Health in 1924 indicated that there was an urgent need to create more playing fields in London due to the loss of land to suburban housing, in order to create a physically stronger male population. In 1926 the ministry requested the LCC conduct a new survey of playing fields within the county, paying attention to ‘the need of open spaces, and especially that of playing fields, for the use of persons residing in London’.15 The subsequent LCC report published in 1929 confirmed that there was a general deficiency of public green space and playing fields despite their impressive figures within the city and in the area of Greater London (7,271 acres and 11,267 acres of green space and 2,157 and 11,124 acres of playing fields respectively). The report showed that almost half of the 6,000 acres of undeveloped land in London could be utilised for playing fields. One of the most pressing problems was however the disparity of vacant land between boroughs. In Woolwich, there were over 2,000 acres of undeveloped land, whereas in Bermondsey, St Pancras and Southwark there was virtually none at all.16 This survey had a profound impact on the policies of many municipal authorities, notably the LCC, providing them with an incentive to create new public green space.

The survey moreover introduced three concepts that became instrumental for the provision of new green space. First was an acreage-based standard. Originally introduced by the National Playing Fields Association (NPFA) in 1925, the standard promoted the provision of 4 acres of public green space for every thousand residents in addition to 3 acres of private playing fields. Acknowledging the scarcity of vacant land, the LCC adopted a more restricted standard of 4 acres per thousand residents for its the future provision policy.17 The LCC and most borough councils considered the proposed 7-acre standard unrealistic.18 Secondly, as one of the first official documents, the survey dealt with the Greater London area instead of just the city, promoting the preservation of private green space outside the city. This was later consolidated as the green belt policy.19 Thirdly, following a modern idea, separated and zoned land uses were promoted as the norm for future planning. Apart from the green belt policy, these concepts played a minimal role in the provision of new green space in the inter-war years.

In addition to the physical fitness of men, the municipal authorities, notably the borough councils, also focused on constructing playgrounds to enhance safer play for local children in response to the increased use of motor cars and congestion on London roads, a problem dating back to the nineteenth century and horse-drawn carriages.20 Streets played a significant role in the everyday life of children, especially in those areas in London where children and teenagers did not have easy access to a park or a playground.21 As the authorities recognised, new playing fields, playgrounds and recreation grounds had to be ‘attractive, accessible, and well administrated’ to compete with the vibrant street life.22 The need to control ‘juvenile delinquency’ gave the authorities another reason to construct enclosed playgrounds.23 Playgrounds for children were included in the provision policies of many borough councils. In 1931 Bermondsey Council, for instance, argued that without a new playground at Rotherhithe Street, ‘the only playgrounds available to the children will be courtyards surrounding new dwellings’.24 The provision of playgrounds intensified when the slum clearances began in the 1930s. This was illustrated in 1937 when the LCC organised a conference on ‘Slum Clearance and Open Spaces’, encouraging borough councils to construct new playgrounds ‘from the poin...