- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

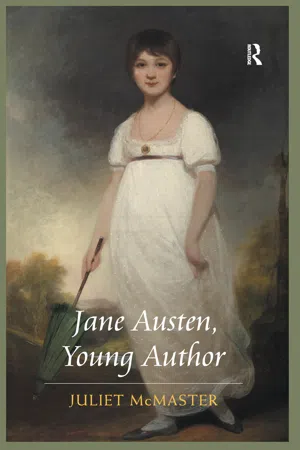

Jane Austen, Young Author

About this book

In her lively and accessibly written book, Juliet McMaster examines Jane Austen's acute and frequently uproarious juvenile works as important in their own right and for the ways they look forward to her novels. Exploring the early works both collectively and individually, McMaster shows how young Austen's fictional world, peopled by guzzlers and unashamed self-seekers, operates by an ethic of energy rather than the sympathy that dominates the novels. A fully self-conscious artist, young Jane experimented freely with literary modes - the epistolary, the omniscient, the drama. Early on, she developed brilliantly pointed dialogue to match her characters. Literary parody impels her creativity, and McMaster's sustained study of Love and Friendship shows the same intricate relation of the parody to the work it parodies that we later see with Northanger Abbey and the Gothic novel. As an illustrator herself, McMaster is especially attuned to the explicit and sometimes hilarious descriptions of bodies that preceded Austen's famous reticence about physicality. Rather than focusing on the immaturities of the juvenilia, McMaster maps the gradual shifts in tone and emphasis that signpost Austen's journey as a writer. She shows, for instance, how the shameless husband-hunting in The Three Sisters and the vigorous partisanship of The History of England lead on to Pride and Prejudice. Her book will appeal to Austen's critics and to passionate general readers, as well as to scholars working in the fields of juvenilia, children's literature, and childhood studies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Energy Versus Sympathy1

Take “Jack and Alice,” which Jane Austen wrote when she was about 13. It has three heroines, one with a red face who is “addicted to the Bottle and the Dice,” one a virtuous widow “with a handsome Jointure and the remains of a handsome face”; and the third a “lovely young Woman” whom we first encounter lying under a citron tree with a leg broken by a man-trap. The eponymous hero, Jack, barely appears. The other hero is “of so dazzling a Beauty that none but Eagles could look him in the Face.” The villainess is “short, fat and disagreeable” (J 14, 17).2 The action includes the breaking and setting of a leg; a masquerade, from which the guests are all “carried home, Dead Drunk” (15); proposals of marriage by a woman; threats and attempts by one lady to cut the throat of another; and a poisoning. Finally the villainess is “exalted in a manner she truly deserved ... Her barbarous Murder was discovered and ... she was speedily raised to the Gallows” (29). Does this sound like the Jane Austen we know? Hardly.

“What Became of Jane Austen?” is the title of Kingsley Amis’s 1957 essay on Mansfield Park. He was staggered that Austen, with her mastery of irony, should have settled even temporarily for what he sees as the dreary moralism of Fanny Price and Edmund Bertram. But the difference between Mansfield Park and Pride and Prejudice, startling though it is (even for readers who have learned to admire Fanny), is as nothing to the difference between Austen’s juvenilia and the novels of her maturity.

One tradition of critical response, originating in the Austen family, has remained faintly embarrassed by the juvenilia, even to the point of considering they should not be published (J.E. Austen-Leigh 46; J. Austen-Leigh 178). Most readers of Austen discover them late in the day, and are either surprised and delighted or mildly shocked, but the “real Austen” for them will remain the six novels. “What Became of Jane Austen?” for them, was that she grew up and became a great novelist, in that order. But for a few eccentrics, or choice souls (depending on one’s point of view), the answer to the “What became of?” question is less positive: she grew up and was tamed. They measure the loss as well as the gains. The Wordsworth of “Tintern Abbey” looks back on the “aching joys” and “dizzy raptures” of his youth, and tries to convince himself, “other gifts / Have followed; for such loss, I would believe, / Abundant recompense.” He does not quite succeed, because he continues to be haunted by that sense that “there hath passed away a glory from the earth” (153).

And so with my reading of Jane Austen. The six novels are indeed “abundant recompense” for the exuberance and dizzy raptures of the juvenilia. And it would be mere perversity to “mourn or murmur” at the passing of Jane’s juvenility. Nevertheless, the opposite extreme is perversity too. It is worth lingering, after all, over “the hour / Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower.” Lingering, and exploring – for if the differences are amazing between the juvenilia and the six novels, so are the similarities. I shall be pondering both the discontinuities and the continuities: the juvenilia as their own separate place of dizzy raptures and the juvenilia as offering intimations of the immortality that is to come.

The Jane Austen who has hit the jackpot of critical success is the novelist of restraint. “First and foremost,” wrote G.H. Lewes, in 1852, pulling out all the rhetorical stops, “let Jane Austen be named, the greatest novelist that has ever written, using the term to signify the mast perfect mastery over means to her end” (Southam, Critical Heritage 140). The qualification about mastery of “means to her end” strikes the keynote of much of the praise that was to come, the claims that she was (surprisingly) great but exact, whereas other great writers, such as Shakespeare, have always been allowed to be great and chaotic. It used to be held one of Austen’s great strengths that she knew her limitations: that she never presented a scene between men in which no women were present (because, after all, she was a woman), and that she never followed her couples into the bedroom (because, after all, she was a spinster). It is rather like praising an athlete for how fast she can run in a hobble skirt. Austen is brilliant for all she can do despite her limitations. But it is wonderfully liberating to take a look at what she could do before she knuckled under and took to that hobble skirt. Her juvenilia are not elegant and certainly not restrained. But they do show that athlete’s extraordinary energy and agility.

“Keats’s amazed delight on first looking into Chapman’s Homer was nothing compared to mine on first looking into Dr. Chapman’s edition of the Minor Works,” records the novelist Reginald Hill of his younger self (79). To a teenage boy who had been thoroughly put off Austen by a compulsory reading of Mansfield Park, the juvenilia were a godsend, an awakening to the proper way into Jane Austen’s work.

What we find in the juvenilia is not an aesthetic of exactness and restraint, but an aesthetic of exuberance, of excess. Here we have no painstaking search for the single mot juste, but a gargantuan delight in plethora. Rich Mr. Clifford, we hear, keeps not just a coach and four but “a great many Carriages of which I do not recollect half. I can only remember that he had a Coach, a Chariot, a Chaise, a Landeau, a Landeaulet, a Phaeton, a Gig, a Whisky, an italian Chair, a Buggy, a Curricle and a wheelbarrow” (51). The “beautifull Cassandra,” on a single visit to a pastry-cook’s, “devoured six ices, refused to pay for them, knocked down the Pastry Cook and walked away” – a lot of action and consumption for a single sentence (54). Charlotte Lutterell of “Lesley Castle,” who is also keen on food, goes to her lodgings in Bristol well supplied: “We brought a cold Pigeon-pye, a cold turkey, a cold tongue, and half a dozen Jellies with us, which we were lucky enough with the help of our Landlady, her husband, and their three children, to get rid of, in less than two days after our arrival” (153). Why use one word when a dozen will do as well? Why restrict yourself to a single long-lost relative when, as in “Love and Freindship,” with a flourish of the pen you can be so much more generous? “Another Grand-child!” exclaims Lord St. Clair, with theatrically uplifted hands. “What an unexpected Happiness is this! to discover in the space of 3 minutes, as many of my Descendants!” (121); and presently a fourth reveals himself. Charlotte Brontë famously denounced Austen for her paucity of passion and lamented the absence of the “bonny beck” and “bright, vivid physiognomy” in her novels.3 And indeed the Austen of the novels is notably sparing in details of personal appearance as of landscape. Not so the Austen of the juvenilia. Elfrida and her companions cheerfully discourse on the “forbidding Squint, ... greazy tresses and swelling back” of the otherwise elegant Rebecca (6).

Such boisterous overstatement is not just over the top, but down the other side too. And while hyperbole is the familiar tool of the satirist, this aesthetic of excess has more than a satiric intent. It is Rabelaisian, carnivalesque, born of a youthful jouissance that is one of the clouds of glory that the mature author has had to leave behind. Far from working with a fine brush on a little piece of ivory two inches wide (as the older Austen described her composition process), this young artist wields a broad and laden brush, sloshing her effects over an area as broad as Tom Sawyer’s fence, producing much effect after little labour.

Consider one aspect of the notable discontinuities between the juvenile work and the mature work: motion. Stuart Tave memorably characterises the mature Austen as a dancer who can move “with significant grace in good time in a restricted space” (Tave 1). He shows how the characters who take liberties with time and space (like John Thorpe, who boasts that his horse cannot go slower than 10 miles an hour in harness, or Mary Crawford, who also stretches distance and duration), are morally tainted. Approved characters observe a strict decorum in these matters. Similarly, the principle that “3 or 4 Families in a Country Village is the very thing to work on” in a novel (Letters 275) implies a commitment to the unity of place that is very different from the wildly unstructured peregrinations that are characteristic of the juvenilia. The young Austen, like Catherine Morland before she was “in training for a heroine,” seems to have delighted in the dizzying motion of “rolling down the green slope at the back of the house” (NA 7, 7).

Free and vigorous motion, in fact, is one of the recurring characteristics of these rollicking narratives. The heroine of “The Beautifull Cassandra” takes a hackney coach to Hampstead, “where she was no sooner arrived than she ordered the Coachman to turn round and drive her back again” (55). Such motion is not purposeful and efficient, but gratuitous, undertaken for its own sake, and so simply pleasurable. She is like the grand old duke of York in the nursery rhyme, who

had ten thousand men;

He marched them up to the top of the hill,

And he marched them down again. (Opie 442)

The irrational and repetitive motion in both cases has its nonsensical appeal for the child. In “A Tour through Wales” the narrator explains,

My mother rode upon our little pony and Fanny and I walked by her side or rather ran, for my Mother is so fond of riding fast that She galloped all the way ... . Fanny has taken a great Many Drawings of the Country, which are very beautiful, tho’ perhaps not such exact resemblances as might be wished, from their being taken as she ran along. (J 224)

When the girls wear out their shoes,

Mama was so kind as to lend us a pair of blue Sattin Slippers, of which we each took one and hopped home from Hereford delightfully. (224)

(I suspect that this passage inspired the slipper-strewn cover design of Christine Alexander’s Penguin edition of the juvenilia.) Fanny’s drawings, though not “exact resemblances,” might stand as emblems for the juvenilia: the vigorous young artist has priorities more lively than mere realism.

The hero of “Love and Freindship” sets out from Bedfordshire for Middlesex – both counties in the southeast of England – but though he prides himself on being “a tolerable proficient in Geography” he finds himself in Wales, in the Vale of Uske (108). The heroines rattle about all over the country, and the memorable last scene takes place in a stagecoach that shuttles to and fro between Edinburgh and Stirling. These indeed are “dizzy raptures,” to appropriate Wordsworth’s phrase for his youth: rhythmic and repetitive motion vigorously indulged in for its own sake. It is the sort of high, like the rides in a fairground, for which the adult loses stomach.

There are gender implications to this wild, unrestricted motion. The value for stability and stasis that characterises the six novels makes them very much a woman’s world. Woman has traditionally been the “fixed foot” (Donne’s phrase), while the man is that part of the compasses that wanders forth and circles round. A recurring trope in Austen’s novels shows the heroine posted at a window, engaged in identifying the mounted male who rides toward her from a distance, as Marianne watches and waits for Willoughby, Elinor for Edward, Elizabeth for Darcy, Charlotte Heywood for Sidney Parker (SS 99, 405; PP 369; MP 493, LM 206). Not so in the juvenilia. Waiting and watching are not congenial activities for the hyperactive personnel there, female or male. They know no boundaries.

The young Jane Austen was still relatively free of a gendered identity, and she presents characters who are similarly unsocialized. In fact, one of her most gleeful recurring jokes is gender reversal.

In “Henry and Eliza,” which she probably wrote at age 13 (Sabor xxviii), she presents a heroine who is a foundling, like Tom Jones, and chronicles the sowing of her wild oats with a Fieldingesque indulgence. Eliza is an adventuress who purloins banknotes, snaps up other girls’ fiancés, absconds to France, and survives motherhood and widowhood. Thrown into prison with her two little boys, she escapes down a rope ladder as resourcefully as any Jack Sheppard. And she is never made to repent of her cheerfully self-indulgent behaviour. Among the assumptions built in to the juvenilia is that girls can be as naughty as boys – in fact, are meant to be as naughty as boys – and that a good adventure is more fun than a morally pointed tale any day. In the denouement of this tale, after she has been reunited with her cheerfully forgiving parents, Eliza raises an army, demolishes her enemy’s stronghold and “gained the Blessings of thousands, and the Applause of her own Heart” (45). No long-suffering forgiveness of enemies for this heroine! And rather than being haunted by the sentimental heroine’s sense of unworthiness, Eliza, “happy in the conscious knowledge of her own Excellence,” takes the time to compose songs in her own praise (34). As Karen Hartnick points out, “Eliza lives out the traditional male adventure – she leaves her family, travels, faces danger, demonstrates cunning and bravery, and defeats her enemies in armed battle” (xiii). The dangerous adversary of the piece is also a woman, the implacable “Dutchess,” who maintains a private army and keeps a personal Newgate “for the reception of her own private Prisoners” (42). There is not much left for the men to do except be snapped up and fought over by the martial ladies.

The Jack of “Jack and Alice” is disposed of in a single paragraph, while the ladies commandeer the stage. And here there is further cheerful reversal of gender roles, this time in the courtship situation. The women of Austen’s generation had inherited the courtship codes laid down by Richardson and the conduct books, according to which the woman’s role in courtship is meant to be not just passive but almost unconscious: she is not to be aware of her own sexuality until the male awakens it by his proposal. In her novels, Austen continues to challenge this ruling (McMaster, Novelist 177), but in her juvenilia, especially “Jack and Alice,” she has more fun completely reversing it. Charles Adams, the man all the women lust after, is the feminized male – “amiable, accomplished and bewitching” – while it is the heroine who is “addicted to the Bottle and the Dice” (14). Like Richardson’s Pamela, though with much less finesse, he finds himself bound in honesty to admit to his own unimpeachable virtue: “I imagine my Manners and Address to be of the most polished kind; there is a certain elegance a peculiar sweetness in them that I never saw equalled and cannot describe” (28). In his behaviour, no less than in his beauty and virtue, he smacks of the heroine. Pursued by love-hungry ladies, he retires to his country estate. This playing hard to get, of course, is very stimulating for the enterprising young women who come a-courting. Lucy, the most persistent of them, will not take no for an answer. Taking over the conventional phraseology of male discourse, she writes to him that she will “shortly do myself the honour of waiting on him” (24). Like Mr. Collins she attributes his “angry and peremptory refusal” of her proposal to “the effect of his modesty” (24). When he will not answer her letters, like Mr. Elton in the carriage with Emma she “choos[es] to take, Silence for Consent” (24). She does not give up until she is caught, appropriately enough, in a man-trap – “one of the steel traps so common in gentlemen’s grounds” (24). Almost in chorus, like a trio of courtly lovers, the women moan iambically, “Oh! cruel Charles to wound the hearts and legs of all the fair” (24).

The female suitors who surround the lovely Charles Adams are quite frank about being attracted by his physical charms rather than by the virtues that he considers are his best claim to being loved. In the novels it is usually the male who is expected to succumb irrationally to beauty, as Mr. Bennet did. But here Lucy admits, “I could not resist his attractions.” And Alice sighs, “Ah! who can” (23).

The same bold reversal of conventional gender attitudes appears in “A Collection of Letters,” where a young girl has no scruple in arguing, “It is no disgrace to love a handsome Man. If he were plain indeed I might have had reason to be ashamed of a passion which must have been mean since the Object would have been unworthy” (209). The long and agonized debates among women in Clarissa and Sir Charles Grandison on the extent to which “person” in a man may legitimately influence a woman’s response are cheerfully set at naught in this epistolary collection. These females are frankly in pursuit of good male bodies and, by implication, good sex. The long tendency of sentimental fiction to etherealize the heroine can hardly survive against this gust of earthy comedy.

“The Beautifull Cassandra,” probably written when Jane Austen was 12 years old (McMaster, Beautifull Cassandra), is again interesting for the heroine’s bold appropriation of the male adventure and for its switch of gender roles in the parents’ generation. Cassandra’s mother, the “celebrated Millener in Bond Street,” is apparently the breadwinner of the family, but when Cassandra returns from her day of conspicuous consumption and unashamed self-indulgence, it is to her “paternal roof” (54, 56). The devoted mother is the effectual head of the family, but the male, absorbed with his “noble birth,” takes the credit. It is an early version, I like to think, of Anne Elliot’s family in Persuasion.

In her love life Cassandra is boldly experimental. The narrative offers the highly eligible Viscount, who is “no less celebrated for his Accomplishments and Virtues, than for his Elegance and Beauty” (another feminized male). But Cassandra falls in love with “an elegant Bonnet” instead, a female accessory created by her mother, and cheerfully elopes with it. The bonnet, however elegant and desirable, is no permanent commitment, but only one prominent item that contributes to the protagonist’s picaresque journey of self-fulfilment. It is mated, used, and discarded, rather like the women in James Bond’s path.

In her narrative voice, too, young Austen often takes over traditionally male territory. The great parodists – Fielding, Sterne, Thackeray, Thurber – have usually been male; but she like them initially found her voice in parodic imitation. In “The History of England,” useful in being third-person and apparently omniscient narration, she takes off Goldsmith’s somewhat pompous tone of authority and turns it into whimsical Shandyism, as in telling her readers that if we don’t already know all about the Wars of the Roses, “you had better read some other History, for I shall not be very diffuse in this” (178). But I shall have more to say on this aspect of her work in later chapters.

Laughter a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Energy Versus Sympathy

- 2 Jane’s Juvenilia Illustrated

- 3 Self-conscious Author

- 4 Greazy Tresses, Base Miscreants, and Horrid Wretches: Teenage Jane Does Dialogue

- 5 “Love and Freindship” in the Classroom

- 6 “Love and Freindship” and its Targets

- 7 Partial, Prejudiced, and Proud: Pride and Prejudice and the Juvenilia

- Works Cited

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Jane Austen, Young Author by Juliet McMaster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.