1 Mattia Pascal and the name of Cyprus

In the introduction to his masterpiece, Mattia Pascal, Pirandello writes that the only thing that the main character of the novel knew was his name.

One of the few things, indeed the only one that I know for certain is that my name is Mattia Pascal. I used to take advantage of this. Every now and then a friend or acquaintance was foolish enough to come to me asking for some suggestion or advice. I would shut my eyes slightly, shrug, and answer: ‘My name is Mattia Pascal.’ – Thanks a million. I knew that ‘Yes, yes I know that much.’ And does it seem so little to you.’ ‘To tell you the truth, it didn’t seem a great deal to me either.’1

When I started my research on Cyprus in the passage from Late Antiquity to the early Middle Ages, I caught myself in the same state of mind as Pirandello’s character. Although a number of important historiographical syntheses on Cyprus in the period under consideration have been published, they seem to me not sufficiently concerned with a comprehensive approach and not fully focused on a systematic analysis and contextualization of the volume of information stemming from different types of primary sources (literary, documentary, and material). Rather, as will be seen, their concern has mainly been to describe the internal history and fortunes of the island in terms of a catastrophic decline and depopulation from the mid-seventh century onwards. As a result of such a descriptive narration, however, they leave the reader to draw the most obvious conclusions about the patterns of discontinuity in the history of Cyprus. Furthermore, because they mainly wish to zoom in on the dramatic and disastrous events that shaped the lives of the local inhabitants, more often than not those calamities are identified, too easily, with the Arab incursions of 649 and 653. According to these sources, after these dates, what we supposedly know about Cyprus is a little more than its name.

Indeed, the idea that the Arab conquest permanently broke the unity of the Mediterranean turning it into a permanent frontier is not peculiar to Cyprus and hearkens back to Henry Pirenne’s Mohammed and Charlemagne. This idea has been challenged and reappraised (particularly in the light of new archaeological evidence) since its first appearance in 1936.2 In the case of Cyprus, the Arab raids have often represented a real watershed moment in the historiography of the island, which often assumes the chronological division of Cypriot early medieval history into three periods: the Late Antique “golden age” (late fourth/early fifth to seventh century), the so-called Byzantine Reconquista (post 965), and the period in between, which is more often than not regarded as the Cypriot Dark Ages. As most attention has been paid to the “golden age” and the Reconquista periods (although the impact of the Byzantine return to the island has started to be debunked), the narrative on Cyprus in the early Middle Ages has been limited to few general topics: above all, a forced (and in fact abortive) transplantation of population to the Hellespont, the encompassing political and religious role of the local autocephalous Archiepiscopal Church, and a treaty dividing the tax revenues of the island “betwixt the Greeks and the Saracens”, that is, between the Umayyads and the Byzantines.3 The treaty, dated to 686–88, supposedly brought about an era of shared political sovereignty between the Umayyads (and later the Abbasids) and the Byzantines. This period, sometimes called condominium, buffer zone, or no man’s land, was regarded by historians as tantamount to a sterile neutralization of the social, economic, and even cultural life of the island. According to these authors, it is only after the Arab invasions and the condominium on the island from late seventh century to 963/4 that a real blossoming of architecture and religious painting can be traced.4 Long gone were the days in which “her [Cypriot] inhabitants toiling their land and trading with foreign nations, were growing in both prosperity and wealth [and] founding temples and churches, building magnificent dwellings”.5

Indeed, in the last few decades, scholars like Andreas Dikigoropoulos, Konstantinos Kyrris, Arthur Megaw, Joannic Durand and Andrea Giovannoni, Robert Browning, Sophocles Hadjisavvas, Vassos Karageorghis, and (at times) Marcus Rautman and David Metcalf have drawn a picture of the period from the late seventh to the early ninth century characterized by repeated destruction, the end of urban life, relocation to inland settlements with fundamental changes in land-use patterns, increasingly rural economic life, and the social and demographic dislocation of the elites, the ecclesiastical hierarchies, and the remaining population of the island.6 In other words, the historiography of early medieval Cyprus often deliberately flirts with catastrophe.7 However, one must recognize that this long-established approach cannot be fulfilling if one wants to properly analyse the historical development of Cyprus in the transition from Late Antiquity to the early Middle Ages through the new cross-disciplinary analysis of different documentary and archaeological materials.8

In my view, scholars who have focused their attention on seventh- and eighth-century Cyprus have been too influenced by the image drawn by the literary and documentary sources alone. It is not that archaeology is completely missing from these syntheses; moreover, a series of conferences held in the Republic of Cyprus in the last few years have indeed brought scholarly attention to the results of field surveys and of urban and rural excavations together with an up-to-date analysis of material evidence.9 However, more often than not the contributions on Cyprus in the passage from Late Antiquity to the early Middle Ages fail to notice the important ways archaeological conceptualization of the passage of time might contrast with that created by a textual historian. This is not to deny that cross-disciplinary boundaries between archaeology and history are very blurred, but simply to assert that one cannot engage with contemporary textual sources as a means to clarify patterns of data recovered from excavations and surveys or use numismatic and archaeological information to address gaps in the written sources.10

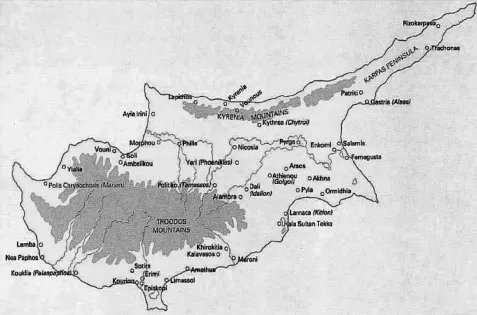

Figure 1.1 A map of Cyprus

For instance, the reduction in coin finds and the dwindling of imported fine wares and amphorae in all excavated urban and rural Cypriot sites has been often interpreted simply as evidence for a retreat of the local population into a more localized economy due to the catastrophic Arab raids.11 Evidence from lead seals and coins has also been used recently to propose the existence of a real north–south divide in the “treaty centuries” (i.e. from 688 to 965), which should help us explain how the condominium regime worked on the island.12 Here, the risk is that of bolstering a picture drawn by documentary sources, more often than not one concerned with raids and punitive expeditions against the island or the predominant role of the Church as a bulwark of the Cypriot religious (and partially political) independence;13 but it is a conclusion derived from these sources, and not independent from them.

It is important to consider that the archaeological past seldom dovetails with the information retrieved from chronicles and other types of literary sources.14 The latter have often either escaped a real critique (for instance in the cases of the Byzantine hagiographies or the Arab sources commenting upon the above-mentioned treaty of 686–88) or have actually been misinterpreted, like the pro-iconophile accounts of the orthodoxy of the island. In other cases, the literary accounts have been deliberately exaggerated, as in the reports concerning the transplantation of the whole population of the island to Nea Justinianoupolis on the Hellespont in 691 or those presenting the ruinous effects of the Arab raids. Moreover, the so-called Cyprus problem (that is to say the de facto partition of the island after the 1974 Turkish occupation of its northern part) has often impinged upon objective interpretations of the period under consideration, prompting the scholarly community to accept the idea that the mid-seventh century ushered the island into an age of deprivation and decline. I will return to this later.

I am also perfectly aware that archaeology, too, has sometimes lacked a methodological critique.15 For instance, Tassos Papacostas stresses that archaeological surveys seldom pay attention to periods later than the Roman Empire and, therefore, rarely edge beyond the historiographical gap represented by the seventh century. Other surveys remained unpublished, as geographical bias does not allow us to use more than a small amount of literature on sites located in the northern part of the island.16 In other words (those of Timothy Gregory), it is ironic that one of the most silent periods of the history of Cyprus is also one of the most recent.17 Uncritical approaches, however, pave the way to flawed generalizations, such as those eager to depict Cyprus simply as a maritime continuation of the Arab-Byzantine frontier.18

In fact, as Dominique Valérian, Ralph Bauer, and Thomas Sizgorich have showed, we should reappraise the entire concept of borders in the medieval Mediterranean. This in the light of a larger Mediterranean analytical approach, which points to the construction of a shared medieval Mediterranean, disputed particularly, although not exclusively, between Christendom and Islam; a sea that remained a border between Christians and Muslims but marked at the same time by conflict and exchange.19 Moreover, the very ontological essence of the term border has been redefined by Sizgorich, who states:

Borderlands are often home to hybrids [which] incorporate and embody the tension of ungovernable and so irresolvable self-other dichotomies confined in a single entity. [However] they also housed individuals and communities who exploited their liminal status and who engaged in economies of various sorts … which existed independently of the great powers between which they abided.20

Ninth and tenth-century Muslim cartographers like Ibn Ḥawqal enhanced this idea, for although they recognized the existence of political boundaries, they defined them as transition zones of uncertain sovereignty and identity where the force of one polity slowed faded away to be replaced gradually by the cultural, social, and political influence of the neighbouring state.21

As will be seen, these concepts of frontier and borderland resurface in the description of Cyprus as a middle ground, based upon the idea that cultures stem from the creative interaction of human populations and never from isolation.22 This reflection takes on universal importance when one considers that this concept has been used to investigate the sixteenth-century interaction between the French and the native Algonquian-speaking people in the Great Lakes region of North America, describing a world that could not be further away from Byzantium and the medieval eastern Mediterranean in terms of geography, climate, social structures, economic infrastructures, cultural values, and religious beliefs. Nevertheless, the concept of a middle ground has a resounding methodological and interdisciplinary echo, for it nurtures the creation of a model for understanding interaction as a cultural process – a process located in a historical place and made possible by the convergence of certain infrastructural elements. These elements are a rough balance of power, a reciprocal need for what the other possesses, and the failure by one side to gather enough force to coerce the other into change.23

Insofar as the elements in question may be replicated in other places and other times, the concept of middle ground can be aptly applied to Cyprus in the transition between Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages, when, as mentioned, the island found itself on the border between the Byzantine Empire and the rising Umayyad caliphate. This situation can also be regarded as quintessential of the medieval Mediterranean generally, which became a border between Islam and Greek and Latin Christendom while remaining a free sea because no one power could dominate the others.24 This is not to discount the violence of the period or to tell a utopian tale of peaceful multiculturalism, but rather to encapsulate Cyprus within a broader Mediterranean narrative. So one could therefor...