![]()

1 Rockites as agrarian disturbers

Rural society in County Cork

This chapter deals with the agrarian dimensions of the Rockites, taking an instance of their activities in County Cork. Cork is the biggest of the thirty-two counties in Ireland in terms of geographical size. In terms of population as well, it was the biggest in early nineteenth-century Ireland, having about 10 percent of the total. How have historians looked at its rural society? Although the first half of the nineteenth century can be regarded almost as a ‘statistical dark age’ for Ireland,1 censuses offer a good starting point. The first complete census in Ireland was that of 1821. While that census was ideal in date to ascertain the social background of Rockites, it only showed ‘the number of persons chiefly employed in agriculture’ and did not make any further distinction within that category.2 The 1831 census is of more use.3 It divided adult males (above twenty years of age) employed in agriculture into three categories, i.e., farmers (occupiers employing labourers), smallholders (occupiers not employing labourers) and labourers.

According to the 1831 census, there existed in County Cork (excluding the city) 171,873 adult males, of whom 125,726 belonged to the farming community.4 Of these 125,726, there were 14,862 farmers, 35,613 smallholders and 75,251 agricultural labourers. The census defined farmers as those who constantly hired at least one labourer, which meant they formed the pillar of the middle class in rural Ireland in the early nineteenth century. While smallholders were practically ‘family’ farmers, they also were basically market producers, forming the lower-middle class in the countryside. At the same time, it was sometimes pointed out that the distinction between them and agricultural labourers was becoming less clear, because of the decline in the living-standard of the smallholders which forced some of them to seek employment by farmers.5 The agricultural labourers were constantly employed by farmers and formed the bulk of the ‘rural poor’. The 1831 census shows that the agricultural labourers formed about 60 percent of the farming community in Cork. This ratio was higher than the national average: in Ireland as a whole, of the total of 1,227,054 men belonging to the farming community 567,441 (46 percent) were the agricultural labourers.

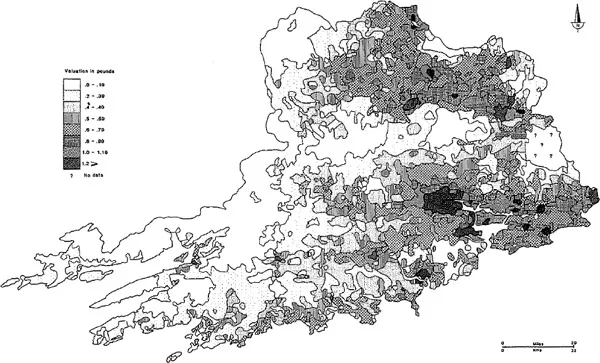

There were several internal differences within Cork. First, in terms of urbanisation and religious composition Cork had a marked gap between north and south. In the early nineteenth century 58 percent of the total Protestant population of the county resided in the south-west of the county, while in 1821 ten of the total fourteen towns of more than 2,000 inhabitants lay in the south.6 The main theatre of Rockites’ activities in Cork was in the rural and Catholic north: four northern baronies of Duhallow, West Muskerry, Orrery and Kilmore, and Fermoy. Secondly, of those four baronies, Fermoy and Orrery and Kilmore can be broadly categorised into a cereal-producing region, while Duhallow (west of) and West Muskerry can be described as a dairy region. The difference between those two regions can be seen in Map 1.1, which shows that the cereal-producing region had a higher land value than the dairy region.

The two regions had a marked difference in another important respect, i.e. social structure. Fermoy barony, to take instance, had a highly stratified society. In 1831 there were 6,385 agricultural labourers employed by 755 farmers, which meant each farmer hired more than eight labourers on average. In contrast, the barony of West Muskerry had 4976 labourers against 1,581 farmers, making the barony less bottom-heavy than Fermoy.7 Fermoy barony had been an old cereal-producing region since the seventeenth century,8 and the region was described as ‘the garden of Ireland’ in the early nineteenth century,9 with five large flour mills, one of which was allegedly the biggest in Ireland.10

The region had a cultural and political centre, Mallow, the second biggest town and the only parliamentary borough in the north of the county. About fifty gentlemen had their seats around Mallow in the latter half of the eighteenth century, and that made the region Munster’s most conspicuously landlord-embellished zone,12 accompanied with the fastest rate of decline in the use of the Irish language in rural Cork in the early nineteenth century.13 Although its heyday was gone, early nineteenth-century Mallow was still called the Bath of Ireland, and according to one account, ‘Pleasure [was] … the object pursued by [its] inhabitants’.14 The town’s keeping its parliamentary seat after the Union played an important role in making it ‘a very disaffected place’.15 It was Mallow which became the most important centre of the Rockites’ underground organisations in County Cork.

Map 1.1 County Cork’s land values, 185111

Some information about agricultural labourers living in the cereal-growing region is provided in a parliamentary committee of 1823. The witness, Sir James Anderson, was a landowner living in the town of Buttevant and running an estate in Fermoy which he inherited from his father. According to him, the agricultural labourer lived and worked in the following way: ‘There is a charge made for the potato garden of the labourer, for the grass of his cow, and for his house, and then, on the other side of the account, the number of days he works is put to his credit.’16 Exchanging labour for land, the agricultural labourer in pre-Famine Ireland was basically a cultivator as well as a labourer, which made contemporaries sometimes call them peasants. The ‘charge’ he paid and the wage he received were in fact nominal, because of the deficiency in the circulation of cash at that time. While this nominal account system could work to the disadvantage of labourers,17 the labourer cited above seems to have been in a relatively better position than others of his class. Another witness testified in 1824 that few of the labourers near Mallow could keep a cow.18

It should be added that an agricultural labourer had other sources of income, in the form of cash, beyond his own labour, i.e. the potato and the pig. Although an ordinary labourer ate nearly twelve pounds of potato a day,19 which suggests he ate little else, an Irish acre (i.e. about 1.6 statute acre) of land, the basic unit for renting, would produce more potatoes than any family would consume in one year. Hence in a year blessed with a good harvest he could make some money by selling potatoes to market or using them to fatten his pigs for sale.20 Though potatoes required much less land than cereals to give the same calorific values, it must be added that the potato was an unreliable crop. There was at least one crop failure somewhere in the island in every two- or three-years in the early nineteenth century.21 In such bad years the rural poor had to reduce the number of pigs they kept, the food of the man and the pig being the same.22 The export of pork from Ireland more than trebled over a period of some thirty years in the early nineteenth century. Because the pig existed basically as a poor man’s cash-earning beast, the fact not only reflects an increase in the number of the rural poor themselves but suggests a deterioration in the living standard of the Irish farming community as a whole.23

The labourer’s ‘landlord’ was not necessarily a landowner but often a farmer who in turn rented a farm from his landowner.24 Farmers who produced cereals needed to put potato cultivation (by labourers) in the crop rotation for the sake of the rehabilitation of soil. About one-third of the cereal-producing land was constantly devoted to potato cultivation in early nineteenth-century Ireland.25 In addition, cereal cultivation needed a much greater labour input, estimated at five times bigger than that of dairy farming.26 These two combined factors in the cereal ...