![]()

Part I Sleep

![]()

Chapter 1

AN OVERVIEW OF SLEEP

William H. Moorcroft

How do you know if someone is asleep? Every child has at one time or another fooled his parents by lying still with eyes closed and breathing slowly. At that time the child pretends to be asleep although is very much awake. At the other extreme, a person in a coma may also be showing outward signs which cause her or him to appear to be asleep. Obviously, then, you cannot easily tell if a person is asleep just by observation. An alternative is to wake the person up and ask if she or he was asleep but this requires depending upon that person’s subjective experience, which is not ideal for scientific accuracy. Furthermore, when the person is awakened, the very thing being studied has been obtrusively interfered with.

The inability to be absolutely sure another person is asleep is important for two reasons. First, sleep has actually not been studied very much because it was difficult to objectively and unobtrusively measure it until about 35 years ago. Thus, much of what is known about sleep is relatively new knowledge (1). Second, it is necessary to study sleep in a sleep laboratory, where the sleeper can be attached to sensitive instruments,* in order to obtain good objective data without disturbing the person’s sleep (2). Since 1953, when Aserinsky and Kleitman first reported that sleeping people have two different kinds of sleep (3), many sleep laboratories all over the world have been engaged in exploring the mysteries of sleep every night.

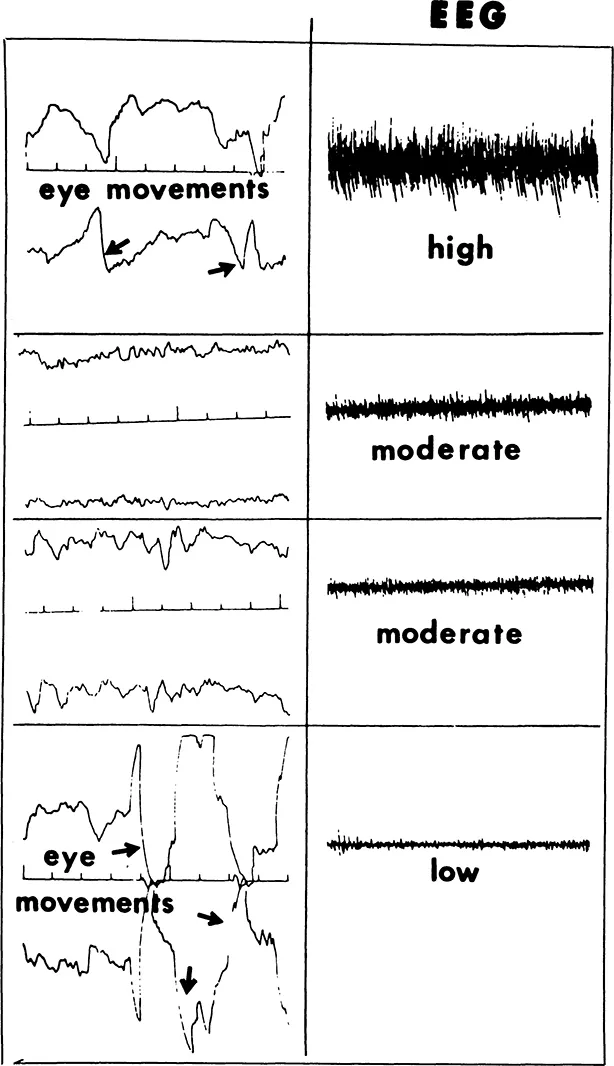

Three modes of measurement are used to determine both when a person is sleeping and what kind of sleep is occurring: EEG, to measure the pattern of the electrical activity of the center of the surface of the brain; EOG, to measure eye movements; and EMG, to measure muscle tone (4). Some laboratories regularly use another set of EEG leads from the back of the head (over the occipital region of the brain) and others eliminate the EMG (5). Additional measurements such as heart beat and breathing movements are often also employed (6). Figure 1 summarizes how the stages of sleep are determined from these measurements.

Fig. 1. Criteria for determining the stages of sleep.

The waking state (also often called stage 0) is characterized by high EMG, eye movements that are rather constant but not as abrupt as those occuring in stage REM (rapid eye movement), and either low voltage (low amplitude on the recording chart), fast irregular waves called beta (over 13 Hz) or moderate voltage, rather regular somewhat slower waves called alpha (8-12 Hz) (4).

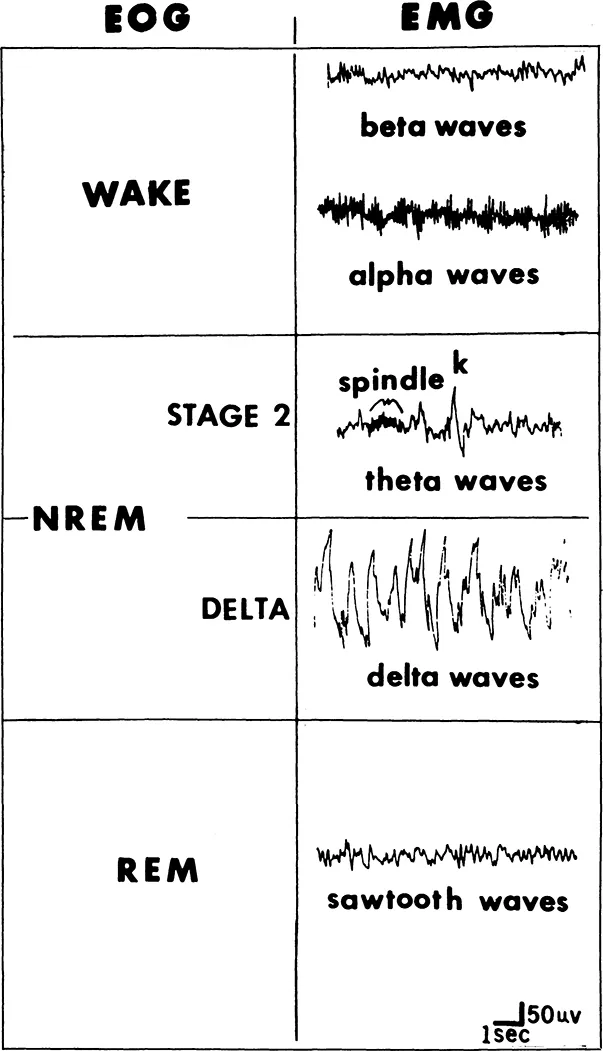

Sleep onset is characterized by slow rolling eye movements (see Figure 2) of several seconds’ or more duration and a mixture of frequencies of relatively low voltage but typically dominated by theta waves (4-7 Hz), usually accompanied by or preceded by a moderation of EMG activity (4).

In stage 2 the EEG shows theta and perhaps a few delta waves accompanied by K-complexes (a high amplitude negative wave followed by a positive wave lasting more than 1/2 second) and sleep spindles (rhythmic 12-14 Hz waves lasting at least 1/2 second). Eye movements are absent and EMG is moderate during this stage (4).

Delta or slow wave sleep is characterized by high voltage (more than 75 MV), slow (1/4-3 Hz) waves (7). At least 20% of the record must show delta waves to be considered this type of sleep. Eye movements are absent and muscle activity is moderate. This stage can be further broken down into stages 3 (20 to 50% delta waves) and 4 (greater than 50% delta waves) (4). Stages 1 through 4 are collectively known as NREM (pronounced non-REM) sleep (8). Older reports may use terms such as quiet, slow wave, or S in place of NREM (9;10).

REM sleep is easily distinguished from the other stages. The EEG is low voltage, random, and fast (“saw tooth” in shape) waves, the EOG shows bursts of usually sharp waves (reflecting rapid eye movements), and the EMG is small or absent (4). This stage of sleep is also known as paradoxical (since the EEG resembles the waking EEG yet the person is, paradoxically, asleep), activated, deep, low voltage fast, emergent or ascending stage 1 (because the EEG sometimes resembles stage 1 and the sleeper is emerging or ascending from deeper sleep), or D-sleep (9;10).

The physiology of the body during REM is quite different from that during NREM. NREM is a sleep of tranquility, REM of physiological storms. During NREM the body processes are very regular and at a low level, but otherwise similar to the physiology of wakefulness. During REM some functions like heart rate and breathing rate can vary wildly and others such as body temperature regulation operate quite differently from NREM and even wakefulness. Finally, and importantly, at this stage the muscles used for body movements are paralyzed so that they are flaccid (11).

Fig. 2. Slow rolling eye movements.

Sleep in the Average Young Adult

The stages of sleep in the average young adult (20 to 30 years of age) show a fairly regular cyclic alteration. While there is considerable variation from individual to individual, the average times described below indicate a general pattern and are based on the work of Williams, Karacan, and Hursch (5).

After the lights are turned out, the beta waves eventually are replaced by alpha. (Some people may not show alpha, yet still have normal sleep and wakefulness.) About ten minutes later the occurrence of slow rolling eye movements accompanies the onset of stage 1. If the sleeper is awakened at this time, s/he probably would report feelings of floating. At other times s/he may experience a myoclonic jerk (a sudden kicking of a leg or thrusting of an arm) which may awaken her/him with a start (2). In either case, s/he probably would have stated that s/he was not really asleep but instead “almost asleep.” However, during stage 1 reactions to outside stimuli are diminished. In an experiment, college students whose eyes were taped open no longer reported seeing when stage 1 started (2). The sleeper might have reported experiencing a “short dream” (12) and her/his thinking might no longer have been reality oriented.

Stage 1 can best be thought of as a transition between wakefulness and sleep that lasts 3 to 12 minutes (5). If it lasts longer it probably will be interspersed with short periods of wakefulness. It certainly is not a deep sleep.

The emergence of K-complexes and sleep spindles signals the beginning of stage 2 sleep. If awakened at this time, a sleeper would most likely say that she/he was truly asleep yet it would not have been too hard to awaken her/him. This first period of stage 2 usually lasts from 10 to 20 minutes (5).

The increasing presence of large delta waves indicates the onset of delta sleep. Waking the sleeper is most difficult at this time; hence, delta sleep is considered the deepest stage of sleep. The average length of the first period of delta sleep ranges from 40 to 90 minutes (5).

Following a brief period of stage 2 sleep again (4 to 10 minutes), which is often preceded and/or ended by a series of body movements, the signs of REM sleep occur. The neck muscle tension reduces to its lowest level, the waves become faster and of lower voltage, somewhat resembling those of wakefulness, and bursts of quick eye movement can be noted. Its onset is 80 to 120 minutes after the beginning of stage 1. This period of REM is typically short (7 to 10 minutes) but may be longer (up to 20 minutes) (5). Intense dreaming typically occurs in this stage.

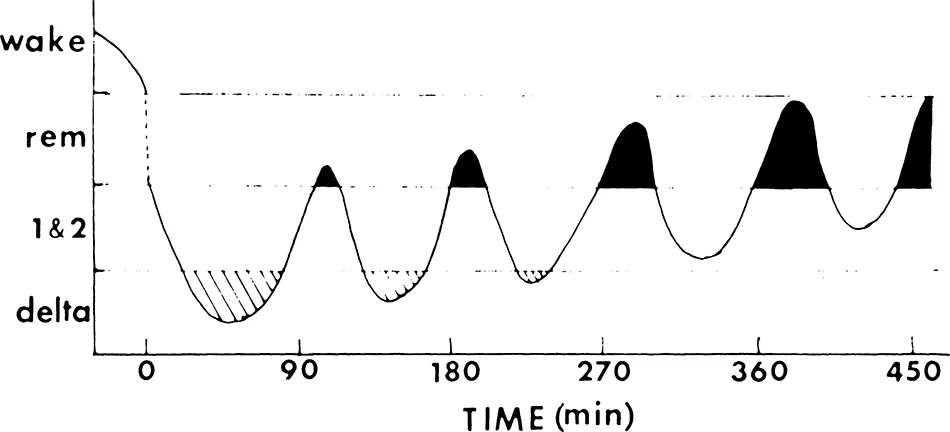

And so the cycle continues throughout the night as shown in Figure 3. About every 90 to 105 minutes another REM period begins (8). But with each succeeding cycle, the duration of REM tends to increase, eventually lasting 1/2 hour or more, while that of delta sleep decreases. In fact, delta sleep rarely occurs during the second half of the night. Most of the rest of sleep is stage 2 with very little stage 1 occurring. This entire pattern is punctuated with an average of 55 movements per night, typically occurring at the point of a stage change and one or two brief arousals to wakefulness (5).

The typical young adult spends about 7 1/2 hours in bed per night. A little over 7 hours of this is spent in sleep (although average total sleep in 24 hours approaches 8 hours if naps are taken into account). Total wakefulness occupies about 1 1/2% of the time between falling asleep and getting up in the morning. REM accounts for about another 25% of this time (or a little less than 2 hours), stage 2 for about 50% (close to 3 1/4 hours), and delta about 20% (about 1 1/4 hours) (1).

Sleep during Other Ages

Not everyone’s sleep is like that of the typical young adult. Some normal young adults differ greatly in length and percentage (but not sequence of stages) from these norms. And even casual experience with babies indicates a pattern greatly different from this. The elderly may show dramatic differences, too (1).

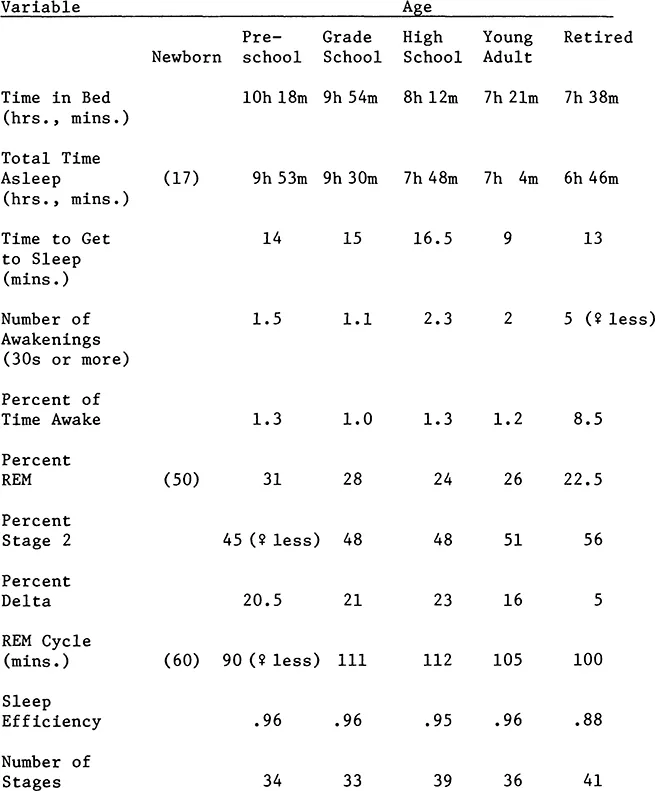

Table 1 summarizes the patterns of sleep typical for various ages (5). The lack of information on the newborn does not reflect a lack of study of the sleep at this age. Quite the contrary, this age has been much studied (13). Sleep patterns at this age are so different that direct comparison with older humans is not possible.

When the sleep of newborns is measured, the same basic EEG, EOG, and EMG measurements are taken, plus measurements for respiration via additional sensors applied to the chest. In addition, every 30 seconds an observer must mark on the sleep record the condition of the baby—whether eyes are open or closed and whether she or he is quiet or active and whether she or he is crying, making body movements, yawning, making facial expressions, etc. (14).

Fig. 3. Idealized night of sleep for a young adult.

Table 1

Average Patterns of Sleep for Various Ages

The characteristics used to categorize newborns are quite different from those seen in adults. These categories are low voltage irregular, high voltage slow, mixed (a random mixture of high and low voltages), and Tracē alternant (several seconds of high voltage slow waves followed by several seconds of low voltage fast waves). Additional characteristics necessary to assess infants’ sleep include eye movements and muscle tone (as in adults), and, as mentioned above, respiration (regular or irregular), body movements (present or absent), and whether the eyes are open or shut.

Combinations of these characteristics are used as criteria for various stages of sleep. The names of the stages as well as their characteristics differ from those used for adults. They include awake, drowsy, active sleep, quiet sleep, and indeterminate state (14). Quiet sleep transforms into NREM as the infant matures. Likewise, active sleep gradually becomes REM sleep. Indeterminate sleep diminishes with age.

The figures for the newborns that are presented in Table 1 are in parentheses because they are gross approximations. The rest are absent simply because nothing in newborn sleep clearly resembles the categories of adult sleep or are otherwise unavailable (6;9;15;16).

By three years of age, a child’s sleep has stabilized enough to clearly compare it with that of adult sleep. As can be seen in Table 1, the time in bed declines with advancing age as does total time asleep. In the first five or so years of life, the number and timing of sleep periods change, as can be seen in Figure 4. Every 24 hours the newborn has multiple periods of sleep separated by short (at first) periods of wakefulness. By one year of age much sleep has “consolidated” into the evening and night but a daily nap period or two remains. By four years of age, the waking time is longer, partially because the nap is later and shorter. Usually by age six the regular nap disappears and all sleep occurs at night (1).

In Table 1 we can see that the time it takes to fall asleep remains relatively stable until young adulthood, as does percent of time awake after going to bed. The number of awakenings during sleep dips from 1 1/2 in the preschooler to about 1 in grade school and rises to 2 by high school. The percent of REM starts high, going from 75% in premature infants to 50% in term infants, settling down to around 25% by high school age. Percentage of stage 2 stays steady at about 50% throughout maturation to adulthood. The percentage of delta is also stable b...