![]()

1 Before the work

Point of view

In the center of a courtyard, Christ stands tied to a column, the smallest person depicted in the whole painting (Plate 2). Two men flagellate him. They are both painted with their right arms raised, perfectly mirrored, one placed with his back to you, the other depicted in three-quarter view. You imagine that the blows of their whips will hit Christ simultaneously. To the left sits Pilate, the Roman consul who ordered Christ to be flagellated. Pictured in profile, he is placed on a podium, from where he watches the scene from close by. You see another man from the back, walking away from you, partly obscuring the flagellator on the left. The space between you and the narrative is meticulously mapped out by evenly spaced tiles. Seven rows of red tiles, a broad band of white marble, and another eight rows of red tiles measure the distance that separates you from the edge of the courtyard. Traverse another three-quarters of that interval and you arrive at Christ’s column.

The room occupied by these five men only makes up half of the picture surface. The right half of the painting is dominated by three standing figures, placed close to you, in front, even, of the first strip of white marble. Standing in an outdoor environment, closed off in the back by some buildings, behind which arises the top of a tree, they are engaged in a dialogue of sorts. The man on the left, depicted in quarter view, is speaking. His mouth is half opened and his left hand gestures. The other two listen, perhaps. But it is difficult to think of them as being engaged in a conversation, for they avoid eye contact. Each of them stands isolated from the two others, a sense of isolation that repeats their separation from the scene unfolding in the background—the scene, which, from the perspective it was painted, takes second place.

Piero stuck to the basic format of Flagellation scenes, dividing the picture up in two groups, the first consisting of Christ, the flagellators, Pilate, and a man sometimes identified as Herod, and a second group made up of the bystanders who had brought Christ in front of Pilate. In some images, Pilate consults with the bystanders; in others, they comment on the event of the flagellation. And then there are pictures, like Piero’s, in which they show a complete lack of involvement. But the way Piero foregrounded the presence of the bystanders was unprecedented.1

The apparent randomness of the picture’s point of view, privileging the bystanders over the main plot, informs other parts of the picture, too. Note how close to the left edge of the painting a column, neatly aligned with the border of the frame, has part of its capital cut off by the picture’s edge, indicating that the painting’s perspective is placed just a centimeter or so too far to the right to show the whole column.2 If the picture’s point of view would have been displaced by that centimeter you would have also been able to see the whole of Pilate’s chair, which now has the tips of its legs cut off by the column in front of it. The chair’s carefully avoiding overlap reveals that the coincidence of the picture’s perspective is at the heart of the picture’s meaning. The cut-offs are just too studied to be the result of some glitch during the painting process.

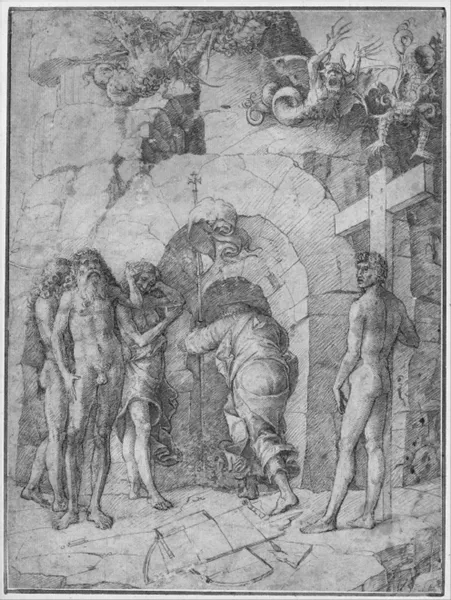

Such studied coincidence also informs the depiction of the man with the turban. Seen from the rear, he is caught in paint at the moment when he reveals least about himself or his place in the story the painting enacts.3 Many Renaissance paintings show figures from the back—bystanders, mourners, and other auxiliary figures.4 But their position rarely interferes with their capacity to “tell” a story. The figure of Christ in Andrea Mantegna’s Christ Entering Limbo (Fig. 1.1), perhaps the period’s most well known Rückenfigur, simply responds to the logic of the picture’s orientation and probes no investigation into Christ’s motives. Piero’s figure is different. He is gesturing like the bearded man in the foreground, perhaps in the direction of the flagellation, contributing to the picture’s narrative without revealing what exactly he is contributing. You don’t know if he has his mouth opened, like the bearded foreground figure. He escapes the control a painter would usually have over his painting, placing his figures in the service of a narrative like a stage director. His placement disturbs the symmetry enacted by the two flagellators, their arms raised by Piero in perfect simultaneity like you only see in pictures. He partly screens the left scourger, with his turban completely covering the flagellator’s right forearm, leaving the hand clutching the whip to hover unconnected in space. Uninvited by this scene of symmetry, the turbaned man’s position is displaced. Or better, he is displaced in a painted world, a world directed by the painter. In your world—the contingent world of lived experience—his position would invite no comment. In painting, a painter was expected to organize the world in such a way that a story, often biblical, was told in a clear way. Leon Battista Alberti heeded to the then dominant ideology of image making when he wrote, in 1435, that “everything the people in the painting do among themselves, or perform in relation to the spectators, must fit together to represent and explain the scene [historia].”5 Piero’s painting ignores that advice. The Flagellation is not ordering a narrative. In some parts, including the man seen from the back, it seems to be imitating the volatility of reality itself.

The man with the turban has turned his back to you in what is perhaps the most absorbed gesture in the history of fifteenth-century painting. He is entirely unaware of your presence in front of the painting. The other figures, too, pretend that they are unaware of the fact that they are placed there for a viewer. None of them acknowledges your presence. They are too absorbed in what happens inside the picture. Christ stares to a corner in the courtroom, the two flagellators concentrate on flagellating him. Pilate watches. The three figures in the foreground converse among themselves without interacting with the viewer. This lack of interaction with a presumed viewer in front of the picture is what sets Piero’s work apart from earlier depictions of the same subject, which usually included a figure looking for contact with you. Alberti had recommended the fifteenth-century painter to make his work respond to a spectator in front of it, defining the artwork as a composition oriented outwards, towards the viewer. He recommended that the painter include a figure in the painting who addressed the viewer and explained to him or her in the clearest possible way what was happening inside the picture.6 Alberti’s idea of a picture responds to the person in front of it, as if the painted figures are actors who seek contact with their audience. Alberti calls the audience of painting “spectatores” (spectators), as if he is writing about actors and their audience. When he recommends the inclusion of a figure pointing the spectators to important aspects in the painting, he is thinking about theater, too.7

Figure 1.1 After Andrea Mantegna, Christ descending into Limbo, ca. 1450, 26.9 × 20 cm, ink and wash on paper. New York City, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection. Artwork in the Public Domain.

The Flagellation rather cultivates the impression that this was a scene discovered by chance, a spectacle witnessed rather than made. Piero was somehow telling you that the narrative was there before he made the image instead of saying that the image ordered or “made” the narrative.

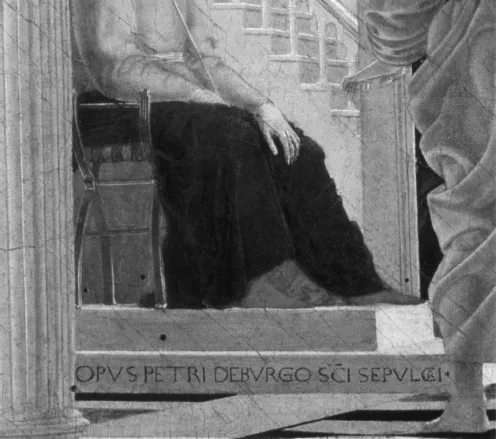

This is a paradoxical claim to make for a painter, at least at first instance. Paintings are emphatically made things, pigments applied to a piece of wood according to a set of decisions made by the painter. A discovery is the opposite of something manufactured.8 To discover is to find something the production of which you do not claim responsibility for, like the discovery of DNA’s double helix. A part of Piero’s picture insists on the fact that it is manufactured, made by hand. Inscribed with Roman capitals on the first step of Pilate’s podium are the words “The work of Piero of Borgo Sansepolcro” (opvs petri debvrgo s[an]c[t]i sepvlcri) (Fig. 1.2). The letters perfectly fit between the column on the left and the left ankle of the man seen from the back. Note especially how the O of “opus” just avoids touching the column in front of it and how, at the end of the inscription, the full stop is placed exactly in between the I and the left ankle of the man standing with his back towards you. There is no off-site or out of sight at the spot where the origins of coincidence is located, where this scene of flagellation is reduced to its moment of making. Yet even if these letters explicate the fact that the painting is an object made by hands, a work (opus), Piero also cultivated the illusion that its letters had already been there before he painted the picture. They are carved in the first step of Pilate’s podium, in ancient Roman letters, like the ancient inscriptions Piero and his contemporaries found on fragments of Roman buildings. (I have more to say about the style of these letters in Chapter 3.)

Figure 1.2 Detail of Plate 2.

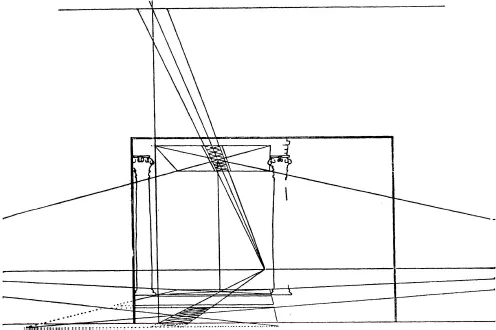

Space/surface

Piero carefully planned his suggestion of coincidence. He exactly measured the position of the figures and the perspective of the architecture and the floor.9 Perspective lines are visible in the rows of tiles, cornices, roofs, and other architectural elements. In 1953, the architectural historian Rudolph Wittkower and the painter and teacher of perspective B. A. R. Carter published two measured drawings of the picture’s plan and elevation, later elaborated upon by Marilyn Aronberg Lavin.10 The Wittkower–Carter reconstruction not only proved that the scale of Piero’s figures and the architecture precisely conforms to their position; it also revealed that the orthogonals meet in one point just left of the colonnade, at the level of the right flagellator’s hips (Fig. 1.3). This point, called the distance or vanishing point, marks the geometrical center of the painting. Yet it is placed on a bare piece of wall.

The placement of the vanishing point in such an inconspicuous place is highly eccentric. Piero knew that this point coincided with the center of vision. It was the place in the picture that offered the clearest view to anyone in front of it. “The eye,” Piero wrote in his treatise on perspective,

is round and from the intersection of two little nerves which cross one another, the visual force [virtù visiva] comes to the center of the crystalline humor, and from that the rays depart and extend in straight lines, passing through one quarter of the circle of the eye, so that this part subtends a right angle at the center [of the picture].

Figure 1.3 B. A. R. Carter, The perspective of Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation, 1953, dimensions unknown. Published in R. Wittkower and B. A. R. Carter, “The Perspective of Piero della Francesca’s ‘Flagellation’,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 16 (1953): 299 (fig. 4). With permission from the Warburg Institute.

He then goes on to say that the ray intersecting with the image at a right angle “is of the greatest strength that the eye opposite from it can see.”11 “In order for the eye to receive the things opposite from it in the easiest way, it is necessary to represent things under a lesser angle than a right one.” All things depicted under a greater angle will not be seen well.12

Before Piero, Alberti had already said that the viewer’s gaze was the strongest in the distance point, and after him Leonardo da Vinci held the same opinion.13 This is why fifteenth-century painters used the vanishing point to impose a sense of hierarchy on the picture. The majority of painters placed the most important figure in their painting in that point. This is where, for instance, Masaccio painted Christ’s face in the Tri...