![]()

Chapter 1

The classroom context

Why should nonverbal behaviour In schools be of interest? The development of human culture is very largely due to our ability to pass on information verbally, so that new knowledge can build on to old (e.g. Humphrey 1976). The school is an institution designed to achieve this strategy, and we might expect the verbal to be paramount over the nonverbal there. However, there are two major reasons for the importance of nonverbal signals. The first is the complexity of classroom life, especially for the teacher, who has to deal with 25 or 30 other people at once. Both when assessing the situation, as it changes from moment to moment, and when she wishes to influence the children's behaviour - often several of them at once - she gains from extra communication channels besides her voice. As we shall see when we look at how the teacher conveys her enthusiasm for her subject (chapter 5) or the children's response to it (chapter 6), the extra communication channels can modify or support what she says. The importance of the teacher's 'manner' has long been recognised (Perry 1908, Waller 1932); the lack of change since Perry's descriptions 80 years ago is striking!

Nonverbal channels are more ambiguous than speech, and this is a second reason for their importance. As outside the classroom, it is often desirable to maintain flexibility and not to take too entrenched positions, especially if there is some degree of conflict (chapters 3 and 5). The ambiguity of nonverbal communication makes it ideal for delivering in a non-attributable way a message which might otherwise have caused offence - for example older children may find overt, direct praise condescending. If their contribution is received with real enthusiasm in facial expression and voice - a smile of surprise and delight, with vocal stress on the appropriate words 'That's it, exactly!' - older children, or adults, will feel it has been welcomed genuinely and without condescension.

The implicit nature of much classroom communication is the cause of many of the problems encountered by new teachers (chapter 10) and where teacher and children have different backgrounds (chapter 9). In the third section of this chapter, therefore, we look at the nature of the classroom social system. The classroom differs from other social settings, but not always in the way which would be expected from explicit definitions of what education is about. Classrooms are supposedly about learning, whether this involves teachers transmitting a specified body of knowledge or children learning on their own initiative. Children do not, though, conform to adults' definitions of their role, but exert strong influence over classroom processes. In this chapter we look at some of the influences on their behaviour; in chapter 2 the development of their nonverbal behaviour is considered in more detail. First however, we need to consider what should be included in the definition of nonverbal behaviour as it applies to the classroom.

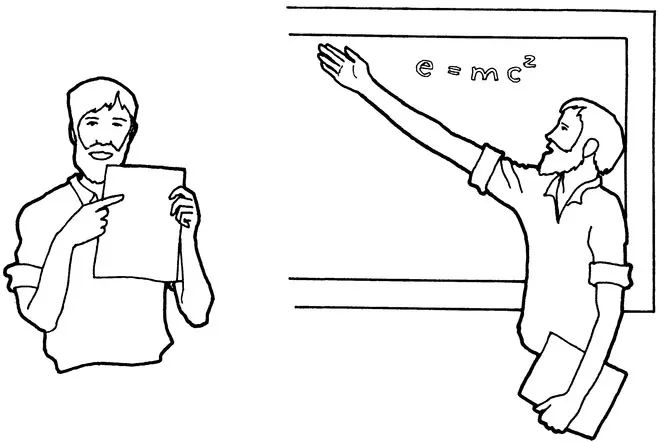

Figure 1.1 Finger point (left); palm point (right). These two points would probably be interpreted as communicatively equivalent, the differences being related to the medium (paper or blackboard) the teacher is working with. In Grant and Hennings' (1971) terms the teacher would be 'directly wielding' the book in the finger point, and 'instrumentally wielding' it in the palm point (in which the book has no communicative significance). His orientation counts as 'indirect wielding'. Thus in the palm point his orientation half-way from the class is explained by the need to see the blackboard and does not have the communicative significance of avoidance it would have if he were reading from the book

What is Nonverbal Communication?

'Nonverbal communication' in education has been taken to cover a wide range (Smith 1979), but in this book attention is concentrated on communicative behaviour, over the school age-range from about 4 to 18. Studies of babies and toddlers before they enter preschool have been excluded, except where they illustrate important points for the school age-range. Much research has been done on adults, especially university students (usually psychologists). Much adult behaviour in non-educational contexts is relevant to the behaviour of teachers; for example the behaviour of other public speakers. Studies of informal social behaviour have also been used to clarify the distinctive features of teachers' nonverbal repertoire. In many of these studies the 'adults' are students. Studies of university students, as students, have been used mainly where they illustrate points about teacher-student interaction which have not been investigated with school-age children. The emphasis on the learner's responsibility in university education, together with the adult level of sophistication which students have reached in their nonverbal behaviour, makes university students a poor model for many of the features of behaviour in statutory-age education.

A number of aspects which have been included as nonverbal communication by other authors are excluded here. Much of teachers' behaviour is 'wielding' (Grant and Hennings 1971) - either 'direct wielding' (handling books, chalk, apparatus, etc.), 'indirect wielding' (looking at the objects she is using) or 'instrumental wielding' (moving into position to use objects) (Figure 1.1). Though these movements have communication significance they vary according to circumstances in a way which makes it impossible to draw generalisations. Thus, after asking a question, one teacher may pick up the chalk (direct wielding) and walk away from the class towards the board (instrumental wielding) while another walks towards the class and the overhead projector and picks up the projector pen. These actions have communicative meaning, but mainly because they are accompanied by more specific communicative actions - waiting for the class's response and gazing at the class, which are described in chapter 6. These communicative actions have to be more invariant to serve their purpose, in the same way as words have to be relatively invariant. Some of the problems which arise when different groups use or understand the same communicative actions in different ways are discussed in chapter 9. The ways in which communicative actions develop are dealt with in chapter 2.

Included are personal space and individual distance (chapter 8), as some authors have felt that these are part of 'human nature'. The use and arrangement of space in buildings, which represents a fixed formalisation of individual distances and relationships, is included (chapter 8), but architectural features such as the presence or absence of windows or the colour of walls, which have been felt to influence mood (Smith 1979, Weinstein 1979), have been excluded.

There has been considerable debate over whether nonverbal communication implies the conscious sending and receiving of messages (e.g. review by Smith 1979). For this book, communication may either be under conscious control or not. As discussed In chapter 2, it appears that in many cases nonverbal signals originate as evolutionarily based actions, which come under conscious control with increasing age. Some signals, such as the leakage of uncertainty discussed in chapters 2 and 3, never come under as complete control as their makers would consciously wish. We might also include fixed signals such as room arrangement, since there is no direct conscious link between their originators and their recipients.

The Value of Nonverbal Signals to the Teacher

The ORACLE study (Galton, Simon and Croll 1980) showed a contrast between the activity and amount of speech produced by the children and the teacher. Primary teachers spent 78 per cent of their time interacting verbally, while pupils spent 84 per cent of their time not interacting. The picture is similar for nonverbal communication. As we shall discuss in chapters 4 to 6, teachers use a wide range of signals to communicate with and control their class. Children's roles in the classroom, and therefore the range of nonverbal signals they use, tend to be more limited. In the later primary and secondary years especially, much of their time is taken up in essentially solitary work (even if a class is working together on the same topic, they may be working in parallel) or listening to the teacher. In these situations their opportunities for active communication are restricted relative to hers. This may suggest that the teacher does not need to know about children's nonverbal abilities.

However, the teacher's problem is in knowing what is going on in the classroom. She can of course check that the class is learning effectively through their written work. However, this involves a delay in feedback; in addition, incorrect answers often do not give enough information on how the child came to make the error. If it is apparent that a substantial proportion of the class is having problems, the teacher may have to repeat her explanation of the topic which caused difficulty. As well as wasting time, this may cause confusion if the class has by then gone onto other work and the repeated work is out of sequence. What the teacher needs is immediate feedback so she can correct any errors or fill in any gaps in understanding as they arise. In normal conversation listeners have ways of signalling to speakers whether they understand the message (Wardhaugh 1985). We explore this topic in more detail in chapter 6, but at this stage we can note two aspects of the problem.

Children may go for long periods in the primary classroom without their serious misunderstandings of topics being corrected when they are doing individualised work, even when they do go to speak to the teacher on a one-to-one basis (Bennett, Desforges, Cockburn and Wilkinson 1984). Bennett et al. attributed this to the teachers' apparent determination to teach the children rather than to find out what their problem was. There was a failure of communication between the teachers and these young (6-7-year-old) children. This was probably at least partly due to the children's inability to recognise and convey to the teacher that her efforts were not getting through.

Talking to the whole class is the most effective way for the teacher to communicate complex ideas (Galton and Simon 1980). This approach does have the disadvantage that the opportunity for individual children to verbally check potential misunderstandings is very limited. Constant interruptions are likely to disrupt the clear organisation of the explanation which is necessary for understanding (Brown and Armstrong 1984). Once children are habituated to the conventions of whole-class teaching they may not interrupt when they do not understand. The teacher may therefore be heavily dependent on assessing whether she is carrying her class with her from their facial expressions. Less successful explainers seemed not to monitor children's expressions and were unaware that they were repeatedly using terms which the class did not know (Brown and Armstrong op. cit.). However, assessing children's response from their facial expressions itself has problems, as discussed in chapter 6. There are severe limitations to their ability to communicate nonverbally, especially in the early years of schooling.

When children first enter education, at 5 or under, their level of communicatory skill, and the social relationships they communicate, differ considerably from those of adults, for two reasons. Firstly, both their transmission and reception of signals are less sophisticated than those of adults, and they may use signals in different ways or not at all. Secondly, since their social relationships with peers and adults differ from those of older children, the selection of signals they use tends to vary correspondingly. For example, young children are more dependent on adults than older children, and more likely to turn to them when distressed. The decrease in touching behaviour with age (chapter 7), in school settings at least, is likely to be primarily due to their changing relationship with the teacher. Older children are seldom in a state of distress where they need a shoulder to cry on.

The Ambiguity of Nonverbal Signals

One major implication which can be drawn from ethological study of nonverbal communication in animals is the ambiguous nature of many nonverbal signals. In the human case, firstly, nonverbal signals differ from words in that several can be emitted spontaneously with the same signal having different meanings according to which other signals are combined with it, and, secondly, in many cases people are not consciously aware of the nonverbal signals they produce in detail and cannot describe them accurately or name them (e.g. Bull 1987). The combination of these two points means that nonverbal signals are less 'attributable' than words and can be used to get a message or attitude across which would not be acceptable if conveyed in speech. There are ways of 'hedging' statements and views in informal social speech such as 'I'm afraid I don't agree' (Wardhaugh 1985) but because of their greater explicitness they are often less appropriate to the more formal and unequal position of the classroom, though they can be valuable in the right circumstances. The general argument of this book is that nonverbal signals are often substituted for verbal ones in the classroom - by moving nearer to a child the teacher can control his behaviour without any overt reprimand, for instance (chapter 7). We will deal with these points in order.

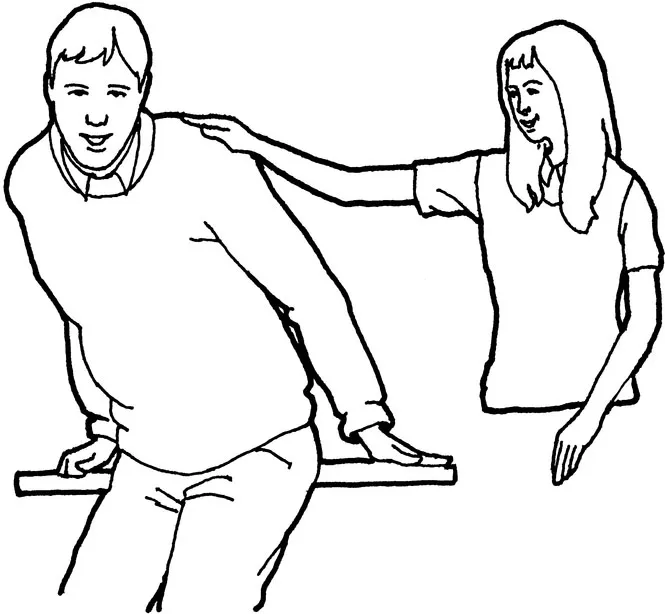

Figure 1.2 Non-communicative intention movement, from a videotape. The teacher leant forward in order to rise from the desk he was sitting on and move away, when the girl touched him. Her touch constituted a challengingly flirtatious invasion of his personal space, as discussed in chapter 7 Source: Reproduced with permission from Neill 1986a

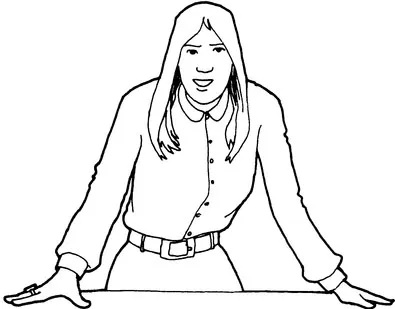

The potential ambiguity of nonverbal signals is well illustrated by increased gaze and forward lean (chapters 4, 6). Like many nonverbal signals, they have their origin in intention movements, which represent preparation for action (Hinde 1974) (Figures 1.2, 1.3). Sustained gaze allows closer monitoring of what someone else is doing, and therefore increased information and greater accuracy in reacting to them, taking action against them or risking a closer approach. Forward lean places one in position, if seated, to get up, and, if standing, to launch oneself towards the other person (chapter 7). Increased closeness places one in a better position for a variety of actions - affectionate, supportive or hostile but, because it exposes one to a similar variety of actions from the other party, it increases the emotional temperature of the interaction. Increased gaze has a similar function; both intensify the effect of accompanying signals rather than conveying a specific emotion. Signals with a range of meanings which depend on the context are widespread among animals as well. A great variety of messages can therefore be obtained from combinations of a relatively small number of signals.

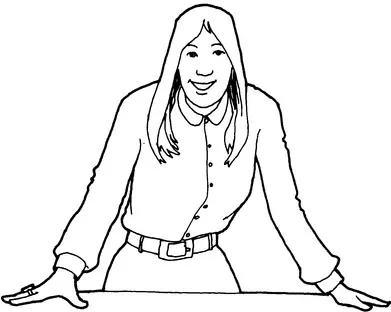

Figure 1.3 Forward lean as an intention movement of involvement. These two pictures were used in a study of the relative effects of posture and facial expression (Neill 1989a). Though the posture was seen positively, as cheerful, friendly and interesting, its effects were weak; children based their judgments primarily on the facial expression

As an example, the level of interest listeners feel in a speaker can be conveyed by posture (Bull 1987; see also chapter 4). Normal speakers respond to these signals, for instance by handing the conversational initiative over to someone else if it is obvious that their listeners are beginning to become bored, without either party explicitly drawing attention to the signals - to do so would be a social gaffe. For a teacher to draw attention to and correct children's listening posture requires a reorientation of attitude (chapter 4). Equally, because of this lack of conscious awareness, emotions which a speaker would prefer to remain hidden may be revealed by nonverbal leakage (Ekman and Friesen 1969a). Ekman and Friesen found that mental hospital patients who were anxious, but not yet ready, to be released, expressed confidence verbally, but leaked their uncertainty, especially through hand and foot movements. The development of children's ability to avoid no...