eBook - ePub

Decision Making in Complex Environments

- 458 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Decision Making in Complex Environments

About this book

Many complex systems in civil and military operations are highly automated with the intention of supporting human performance in difficult cognitive tasks. The complex systems can involve teams or individuals working on real-time supervisory control, command or information management tasks where a number of constraints must be satisfied. Decision Making in Complex Environments addresses the role of the human, the technology and the processes in complex socio-technical and technological systems. The aim of the book is to apply a multi-disciplinary perspective to the examination of the human factors in complex decision making. It contains more than 30 contributions on key subjects such as military human factors, team decision making issues, situation awareness, and technology support. In addition to the major application area of military human factors there are chapters on business, medical, governmental and aeronautical decision making. The book provides a unique blend of expertise from psychology, human factors, industry, commercial environments, the military, computer science, organizational psychology and training that should be valuable to academics and practitioners alike.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART 1

Characteristics of Complex Decision Making

Chapter 1

Decisions about “What” and Decisions about “How”

We assign a moment to decision, to dignify the process as a timely result of rational and conscious thought. But decisions are made of kneaded feelings; they are more often a lump than a sum. Thomas Harris, Hannibal, p. 162

Introduction

Research into decision making has traditionally focused on how people – as individuals – choose among alternatives and specifically about how they go about finding the best alternative or making the “right” decisions. This is most clearly expressed in the three assumptions that characterise the rational decision maker, the homo economicus (Lee, 1971). The first assumption is that a rational decision maker is completely informed, which means that s/he knows what all the possible alternatives are and what the outcome of any action will be. This presumably includes both short-term and long-term outcomes. The second assumption is that a rational decision maker is infinitely sensitive; hence s/he is able to notice even the slightest difference between alternatives and use this to discriminate among them. One consequence of this assumption is that two alternatives never can be identical, as they will always differ in some way. The third assumption is that the decision maker is rational, which implies that alternatives can be put into a weak ordering and that choices are made so as to maximise something. The weak ordering means that if for three alternatives A, B, and C, the decision maker prefers A over B, and B over C, then the decision maker must also prefer A over C. This in turn requires that there is a common dimension, which can be either simple or composite, by which all alternatives can be rated. This common dimension also enables the decision maker to identify the alternative that has the highest value, hence to maximise his or her decision outcome.

Decision making as an identifiable process

The origins of looking at decision making as an identifiable process can be found in the early history of thinking, possibly beginning with the development of logic. Broadly speaking, a decision is supposed to be the result of rational reasoning, which is exactly what logic is about. The doctrine of the rationalist school of thinking, which goes back to Plato, is that human knowledge can be derived on the basis of reason alone, using self-evident propositions and logical deduction. Aristotle formalised the idea of rules of logic and the notion of a logical proof, by means of which one could determine whether a conclusion was true or false. This established the tradition of rational thinking – hence of making a rational decision – and the requirement that the conclusion or decision must be consistent and logical, that is, that it must be understandable according to some rules or criteria; otherwise it is called irrational. The same ethos is found in the question from Chevalier de Méré to Blaise Pascal about whether to accept a bet for a specific outcome in a game of dice. This was reformulated into a question of whether one outcome was more likely than another, with the logic of rationality dictating that the decision should be to choose just that. (In Chevalier de Méré’s problem, one alternative was that at least one six would appear within four throws of one die; the other that there would be at least one double six within 24 throws of two dice. Since the probabilities of the two events are 0.5177 and 0.4913 respectively, the rational decision is to choose the first alternative and forget the other.) This problem was formulated in 1654 and is generally seen as the start of probability theory, which has been of paramount importance to decision making.

The assumptions of the homo economicus refer to the nature of decision making as a process, as something that takes place in the mind of the individual decision maker. Even for organisations, collective decision making “boils down” to what individual decision makers do and the collective is expected to behave just as rationally as the individual. Although the assumptions about the homo economicus have rightly been criticised as psychologically unrealistic (Edwards, 1954), they are nevertheless entrenched in the architecture of many decision support systems. These generally aim to replace by machines what humans are bad at doing, echoing the compensatory principle associated with the Fitts’ list of function allocation (Dekker and Woods, 2002; Fitts, 1951). They thereby preserve the illusion that decision making is a rational process, and that it is only because of some noticeable human shortcomings that rationality does not manifest itself in practice. Yet this endeavour is unlikely to succeed because it falls prey to what Bainbridge (1983) termed the “ironies of automation”. In this case it means that we attempt to use technological artefacts to compensate for a function or process that we cannot describe precisely.

Decision making as an activity

It is, however, possible to see decision making as an activity or a phenomenon rather than as a process, thereby replacing the idealistic assumptions about a rational decision maker with a more realistic set of assumptions about decision making as a facet of work. These assumptions are:

• Decision making is not a discrete and identifiable event, but rather represents an attribution after the fact. In hindsight, looking back at a specific event or activity, we can identify points in time where a decision “must” have been made in the sense that the events could have gone one way rather than the other (Hollnagel, 1984). Yet this does not necessarily mean that the people who were involved made an explicit decision at the time, even though in hindsight they may come to accept that they did. This first assumption also points to an interesting similarity between the conceptual status of “decisions” and of “human error”, cf. the discussion of the latter in Woods, Johannesen, Cook and Sarter (1994).

• Decision making is not primarily a choice among alternatives. It is very difficult in practice to separate decisions from what is otherwise needed to achieve a decision maker’s objectives, that is, what is required to implement the chosen alternative (for example, Klein, Oranasu, Calderwood and Zsambok, 1993). A decision cannot be made without some information about the situation, the demands, and the possibilities of action. Yet the extent (quality and quantity) of that information may indirectly favour one outcome rather than another. Even worse, a lack of information about something may severely curtail the choices that can be made. Similarly, a decision in most cases also requires actions to ensure that the expected outcomes obtain. It is therefore proper to ask whether the term decision making should be restricted to the “moment of choice” or whether it should also cover what goes on before and after.

• Decision making is not usually a distinct event that takes place at a specific point in time, or within a certain time window and which therefore can be dissociated or isolated – even if ever so briefly – from what goes on in the environment. Decision making cannot be decoupled from the continuous coping with complexity that characterises human endeavours (Hollnagel and Woods, 2005). This assumption is superfluous only if decision making is noticeably faster than the changes in the environment, but this condition is rarely made explicit.

The problems arising from the last assumption have been addressed by the theories of dynamic decision making (for example, Brehmer, 1992), although these still see decision making as a distinct process rather than as a facet of human work and activity. There are some really fundamental problems arising from the fact that decision making, whatever it is, takes time and therefore logically requires that the information it uses remains valid while the decision is made. Despite the obvious importance of time – for decision making as well as for human actions in general – few models of human behaviour take this into account (Hollnagel, 2002). Yet rather than getting lost in this fascinating issue, the rest of the chapter will consider the consequences of seeing decision making as an activity rather than a process. This reflects the fact that the problems people have when managing complex and dynamic processes are not so much about what to do, as about how and when to do it. Indeed, decision making is less a question of choosing the best alternative than a question of knowing what to do in a given situation as described, for example, by the school of naturalistic decision making.

This can easily be illustrated by considering the use of procedures in a job. A procedure is an explicit and detailed description of the actions required to achieve a specific purpose, whether it is a recipe for making spaghetti carbonara or the emergency operating procedures to recover from a tube rupture in a nuclear power plant. The procedure is an externalisation of decision making so that the user can concentrate on when to do something rather than struggle with finding out what to do. Deciding on when to do something is, of course, also a decision of sorts, but it is qualitatively different from those that decision theory generally has focused on.

Decisions and actions

It is a consequence of changing the view of decision making from being a separate process to being a facet of work and of acknowledging the paramount importance of time that the three assumptions implied by rational decision making are no longer tenable. The first assumption, complete information, cannot be upheld because the environment is dynamic rather than static. Complete information can therefore only be achieved if all the necessary information can be sampled so fast that nothing changes while the sampling takes place. The second assumption, infinite sensitivity, is untenable for the same reason, namely that it would require time to differentiate among alternatives. The third assumption, weak ordering, must be abandoned because people normally do not have time to consider all the alternatives they have found, even if it is not the complete set. For instance, a study of how senior reactor operators in a nuclear power plant diagnosed disturbances showed that they used a non-compensatory approach. “When people adopt this approach, they reduce the number of alternatives by selecting the most important attributes, instead of performing trade-offs among them. This reduction will be continued until one alternative remains …” (Park and Jung, 2003, p. 210). In practice there is rarely time to match all alternatives against each other, even if a common evaluation criterion could be found. Quite apart form that, numerous studies have shown that people in practice often have problems in making transitive orderings of alternatives (Fishburn, 1991).

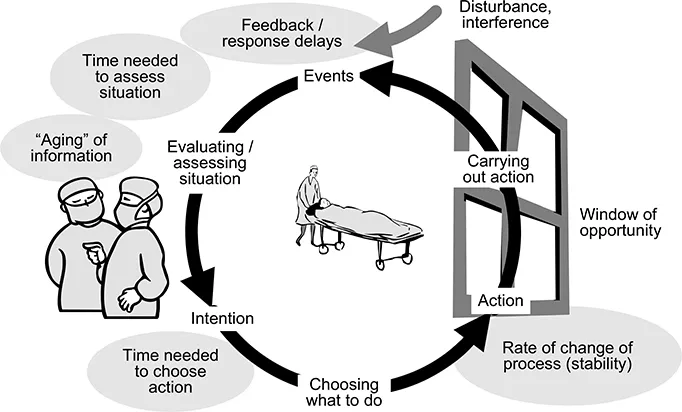

When decision making is described as an activity, the relation between time and decision making can be seen as a special case of the relation between time and actions. This relation can be represented by the contextual control model (COCOM; cf. Hollnagel and Woods, 2005), which describes how the ability to maintain control depends on the controlling system’s interpretation of events and selection of action alternatives (Figure 1.1). At the heart of the model is a cyclical relation linking events, intentions and actions where in particular the two arcs called “evaluating / assessing the situation” and “choosing what to do” are relevant for the present discussion. Associated to the former is the time needed to evaluate events and assess the current situation, while associated to the latter is the time needed to select the action alternatives that will bring about the desired outcomes. The time needed to accomplish both of these must be seen in relation to the time that is available for carrying out the action, represented in Figure 1.1 as the window of opportunity.

Figure 1.1 The contextual control model applied to decision making

Decision making in the traditional sense can be seen as the interface between the evaluation of the situation and the choice of action, or perhaps as a combination of the two. Based on the COCOM, it is clear that time plays a role in several different ways. The evaluation of the situation is susceptible to delays in feedback or responses from the process or application being controlled, as well as to the aging of information. This in itself depends, among other things, on how long the evaluation takes, which leads to an intricate coupling between the two. The choice of action depends on the stability of the process and on the window of opportunity. In many cases it is more important to do something quickly than to spend time on finding the optimal action. In other cases there may be limited time in which to carry out an action, and an alternative that is quick to implement may therefore be preferred over one that takes longer although that in other respects might have been better.

Balance between feedback and feedforward

In practice people are well aware of these dynamic dependencies and usually try to reduce the time needed to evaluate and choose in several ways. Efficient performance depends on an equilibrium between being proactive (relying on feedforward) and being reactive (relying on feedback), which people usually are able to achieve provided the work environment is reasonably stable. If performance is dominated by feedback control, that is, by mainly reacting to what happens, people may soon find themselves in a situation where they lag behind, which invariably will aggravate any shortage of time. In extreme cases, a dependence on reactions means that it is impossible to make any plans, hence to be prepared for what may come.

In order to avoid this, people try to look ahead in order to be able to respond more quickly. The use of anticipation or feedforward control gains time by reducing the need to make a detailed evaluation of what happens and of the feedback; by being prepared to respond, actions may be taken faster and the necessary resources may be made ready ahead of time. Looking ahead, however, also requires that not all the time is used to evaluate the feedback and that the risks from ignoring part of the feedback are sufficiently small. The disadvantage of relying on feedforward control is that the expectations or predictions may be inaccurate and that the prepared response therefore may be inappropriate. This risk clearly increases the further ahead the decision maker tries to look. If the predictions are inaccurate then the chosen actions may lead to unexpected results, which in turn increases the time needed for evaluation, hence increases the role of feedback. In terms of this balance, decisions can be seen both as buying time – by enabling the controller to be ahead of developments – and as using time. It is therefore important both that it does not take too long to make the decision and that the actions are carried out at the right moment and with the right speed.

Efficiency-thoroughness trade-off

One way of reducing the time needed to make a decision is to be sufficiently rather than completely thorough in the evaluation of the situation and in choosing what to do. This is a well-known phenomenon in decision theory and has over the years been referred to by names such as muddling through (Lindblom, 1959), satisficing (March and Simon, 1993) or recognition-primed decisions (Klein, Oranasu, Calderwood and Zsambok, 1993). Trading thoroughness for efficiency, an efficiency-thoroughness trade-off (ETTO) principle (Hollnagel, 2004), makes good sense since there is never infinite time or infinite resources available for the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Foreword

- Part 1: Characteristics of Complex Decision Making

- Part 2: Areas of Application

- Part 3: Complex Decision Making in Civil Applications

- Part 4: Complex Decision Making in Military Applications

- Part 5: Teams and Complex Decision Making

- Part 6: Assessment and Measurement

- Part 7: A Final Comment

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Decision Making in Complex Environments by Jan Noyes, Malcolm Cook, Jan Noyes, Malcolm Cook, Yvonne Masakowshi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Labour & Industrial Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.