![]()

1 Height + 0.00 metres

Centre civique

Following World War II, Le Corbusier prepared several plans to revitalise and rebuild a series of French cities that had been destroyed during the conflict in an attempt to provide new housing for a significant part of the population. Examples of this are the La Rochelle La Pallice (1945), Saint-Dié (1945) and Vieux-Port et Marseilleveyre (1945) projects, to name a few. These projects apply the city model he described as the “linear industrial city” in The Three Human Establishments1 or apply the Theory of the “7Vs”. Moreover, these are projects that use the housing model which he designated the “housing unit”, and the idea of a public area which he named the “civic centre”. Within this group, the Saint-Dié plan comes to the fore as Le Corbusier himself regarded it as a prototype of the Corbusian city of this time.2 Its analysis, and in particular the analysis of its civic centre, then became fundamental to understanding the major premises that define the Corbusian concept of public space of congregation and representation of the collective population of a linear industrial city in the period immediately following World War II.

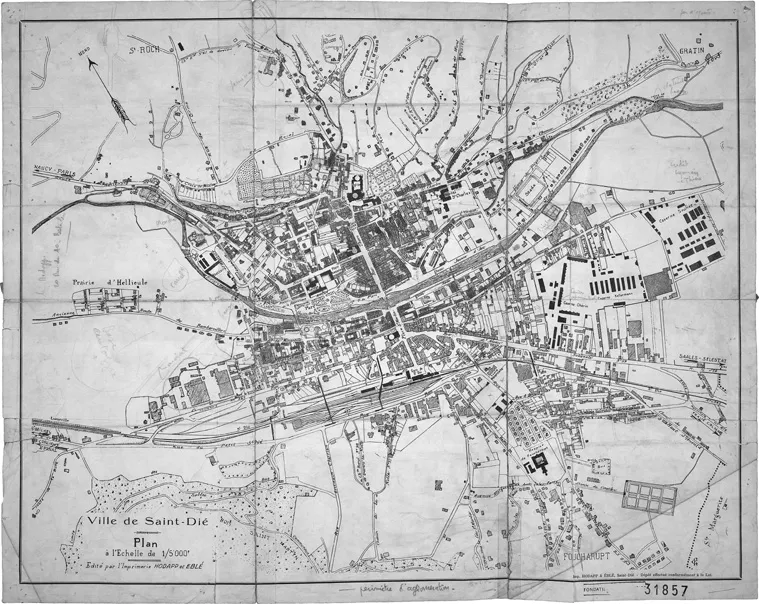

Le Corbusier’s project for Saint-Dié (today called Saint-Dié-des-Vosges) was carried out between April 1945 and February 1946. It consisted of a plan for a city of approximately 20,000 inhabitants and capital of the Vosges District, located along the Meurthe River at the foot of the Vosges Mountains in southern Lorraine, near the border with Alsace in northwestern France. It was a city of narrow streets which had been destroyed by the war. Its buildings were no more than three stories high, with a central shopping area crossed by the Rue de Thiers and dominated by the cathedral. There was an urgent need to provide housing for approximately half of the residents and to rebuild the city, which was almost completely destroyed during the war, the most damage occurring on 9 November 1944 (Figure 1.1).3

Raoul Dautry, Minister of Reconstruction and Urban Planning, visited the city on 17 February 1945.4 Although he provided financial aid for the reconstruction process, he did not mandate any architectural guidelines, explaining why most decisions were delegated to local authorities. At the time of Dautry’s visit, several groups of citizens had been formed to draw attention to their particular interests. They were the Association des Sinistrés (Victims’ Association), led by Jean-Jacques Duval, a local industrialist and friend of Le Corbusier,5 and the Association Populaire des Sinistrés. In February, Duval convinced Le Corbusier to take on the role of consulting-architect of the Saint-Dié Association des Sinistrés. After Jacques André, an architect from Nancy, was appointed urban planner of the city on 19 April of that same year, Duval endeavoured to get Le Corbusier appointed as urban consultant of Saint-Dié, even if such a position was not recognised by the French Minister of Reconstruction and Urban Planning.6 Nevertheless, Le Corbusier believed that Jacques André, a friend of Jean Prouvé, would be able to collaborate in the implementation of a modern city. First, Le Corbusier devoted himself to studying the construction of temporary housing for the population but very quickly began studying a plan for the overall rebuilding of the city. He did it with the support of two young associates, Roger Aujame and Hervé de Looze, who sketched most of the drawings, and also with the contributions of Gérald Hanning, Jerzy Soltan and André Wogenscky.

Figure 1.1 Saint-Dié plan, highlighting the buildings destroyed during the war (FLC 31857).

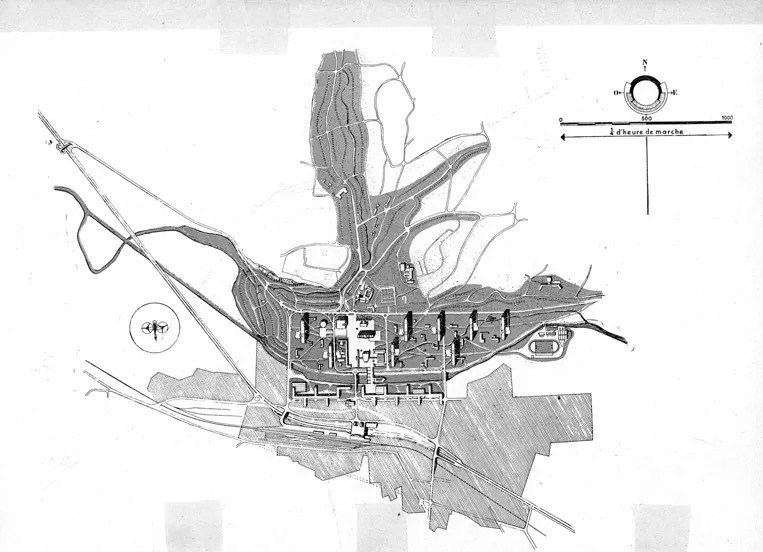

Given that not much was left of old Saint-Dié after the bombings, Le Corbusier saw this project as an opportunity to apply the principles of the Athens Charter (Figure 1.2). In fact, in this city Le Corbusier finds everything he needs to prepare the foundations of a modern city: a splendid geographical context, historical heritage and the prospect of building an open city. In addition to the Meurthe River in particular and the city’s geographical setting in general, three pre-existing buildings were used as reference points for the project: the cathedral, the church and the railway station. All of them occupy a peripheral position away from the historic centre (the first to the north, the two others to the south). The new Saint-Dié would thus be developed on a strip perpendicular to the axis that joins the cathedral and the church. To the north of the river stands the residential area, made up of collective housing buildings of the unité d’habitation type—four to eight—each housing 1600 inhabitants, among which several smaller public buildings can be found. To the south, along approximately 1200 metres, we find the industrial area, designed according to the “green factory” principles. In essence, the city extends in two swaths in the east-west direction, without limits and as such without periphery. The city plan showed the potential for unlimited urban development to the left and to the right, mirroring any growth in population and economy. At the centre of the project, more or less in the area where the old quarter used to be, stands the public space that Le Corbusier named the “civic centre” or the “heart of the city”. With its northern and southern borders delimited by the use of different pavements and its eastern and western ones by two of the eight housing units, a quadrangular enclosure for communal buildings is formed. This is a very special area in the plan, and reference to it appears in all Corbusian publications that comment on the project. Of the 93 urban development project drawings undertaken by the Rue de Sèvres atelier found at the Le Corbusier Foundation in Paris,7 49 have records that relate to the composition of this space and it is thus quite useful to analyse them.

Figure 1.2 Plan for the reconstruction of Saint-Dié (L-C, FLC H3-18-205-002).

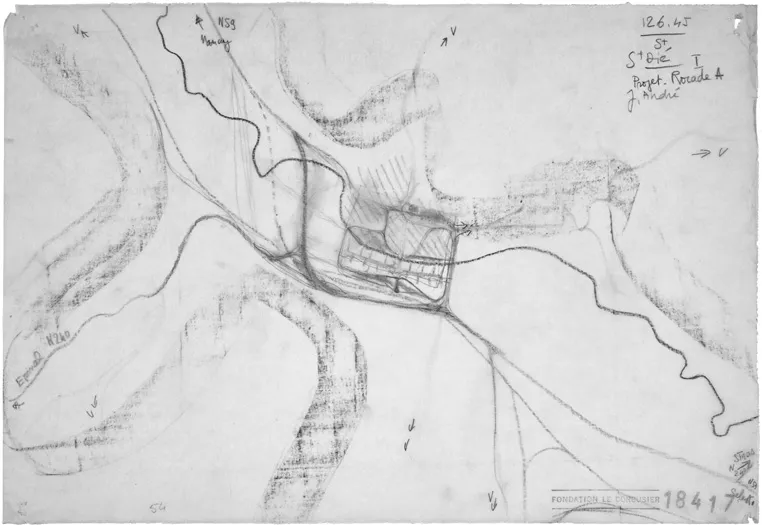

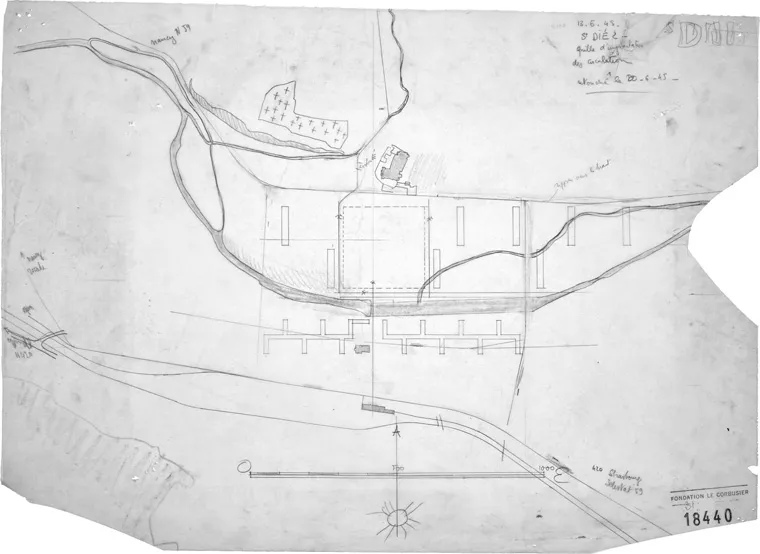

The Saint-Dié project began on 1 June 19458 at a regional level with an analysis conducted of the city’s topography and geographic context. Following a few days of incubation, on 12 June 1945, two studies were prepared, so that the national road—which previously ran through the city as its main road, the Grand’Rue—would no longer cut through Saint-Dié and would be diverted to a more peripheral location (Figure 1.3).9 On the same date, drawings emerged that included the area of the former city centre (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3 Plan for the reconstruction of Saint-Dié (L-C, 12 June 1945, FLC 18417).

Figure 1.4 Plan for the reconstruction of Saint-Dié (L-C, 12 June 1945, FLC 18446).

The next day, a drawing was made where the river and three pre-existing buildings were sketched: the cathedral, the church and the railway station (Figure 1.5). Factory buildings were placed to the south of the river and eight housing units to the north. In part of the territory which had previously been occupied by the historic city centre, a space was especially selected, delimited by the cathedral to the north, by the river to the south and by housing units to the east and west. It is a square-shaped enclosure, with each side measuring approximately 300 metres, where the public life of the city is to be established. This space, identified by Le Corbusier as “civic centre”, is marked in the drawing using dashed lines. Around the civic centre, the main traffic routes are outlined. Contrary to what was the case in urban development projects, such as the Contemporary City dated 1922 or the Radiant City dated 1932, this city’s main roads did not have an aesthetic purpose, and the goal of the road traffic implementation grid was not that of maximum efficiency for road transport.10 The circulation axes and buildings became completely independent entities, which led to a separation between cars and pedestrians (as Le Corbusier had stated in Looking at City Planning,11 which was probably based on his analysis of the city of Paris during the Nazi occupation). Therefore, road traffic became visually absent from areas of public life, of which the civic centre is the ultimate expression. Contrary to what was the case in the 1922 Contemporary City of three million inhabitants, the road traffic routes do not enter the civic centre (peripherally bypassing it), the railway line does not run through it (ending at the existing station, to the south) and the airport is not within the city limits (although a heliport is within these limits).12 The Saint-Dié civic centre is not intended for cars, trains or planes, as is the town centre of the Contemporary City, and neither to cars as in the Plan Voisin centre, but only to pedestrians. In this context, Le Corbusier later stated: “Vehicles are prohibited from passing through the civic centre; it is restricted to pedestrians only”.13

Figure 1.5 “Traffic implementation grid” (L-C, 13 June 1945, FLC 18440).

Thus, it became urgent to define the new city centre programme. On that same day, 13 June 1945, the requirements to be considered were listed: municipal buildings (city hall and administration centre), commercial buildings, buildings linked to crafts and tourism, as well as spaces for performances and expressions of political life. These are all public spaces for administration, representation and the glorification of the population of the city as a whole. The programme was thus reflected in a large sketch (Figure 1.6) and, on the following day, 14 June 1945, a plan was drawn (Figure 1.7). The axis that goes from the old railway station, running along the old Rue de Thiers, widens inside the civic centre enclosure and turns into a sort of boulevard surrounded by buildings and ends with a distant view of the old cathedral. West of the boulevard are three volumes: a large café, a cinema and a coffee shop. To the east, there are several buildings and public spaces. To the north, there is a series of three buildings: one that incorporates a large warehouse, another that incorporates a municipal hall and a third that houses a post office. To the east, there is a set of two buildings: one tall parallelepiped-shaped building on pilotis, which houses the municipal services—a sort of smaller version of the Algiers skyscraper—and a shorter building that houses the city hall and prefecture room. To the southeast, standing alone, there is a square, spiral-shaped museum, following the unlimited growth model of the 1931 Paris Museum of Contemporary Art and the model shown in The home of man. At the centre, a theatre, conceived following the model of the 1930 Palais des Soviets room. The inclusion of a courthouse is also taken into consideration. Whilst the first drafts of the plan represented the drawings of housing units and factory buildings with a repetitive nature, these drawings represented an exception in the plan. Th...