1 Native Sovereignty, Intergovernmental Conflict, and the Uncertainty of Taxes

On August 13, 2010, New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg offered advice to the New York state governor, David Paterson, on how to collect state excise taxes on cigarettes sold to non-Indians on Indian reservations: “Get yourself a cowboy hat and a shotgun.” Bloomberg’s incendiary comment, which he offered during a weekly radio show, reflected decades of conflict between the state and Native nations over cigarette taxes (Moses 2010). In the same month, Paterson noted on a different radio program that state troopers were on “high alert,” preparing for the state enforcement of cigarette taxes on reservations, as “there could be violence and death” (Meyer and Fairbanks 2010). In response to the impending attempt at cigarette tax enforcement as well as fairly unveiled threats such as the one earlier, Native peoples around New York state engaged in protests and demonstrations, initiated lawsuits, and began to prepare for another battle in what had already been a very lengthy conflict.

The dispute over state authority to collect taxes on reservations comes out of a long and complex history of federal, state, and Native relations. Cigarette taxation has been a particularly contentious component of the larger issue of intergovernmental relations between Native nations and states. The moment of protest in Image 1.1 reveals the heart of the conflict. In New York, state officials have seen the issue as one of economics and “lost” taxes, with financial stakes that are high enough to merit costly and effortful enforcement action. For Native nations, state actions threaten not only their income and economic independence but also their basic rights and recognition as sovereign nations. Leaders and activists argued that state taxation violated their rights as nations, which had been guaranteed by the federal government through treaty arrangements.

In New York state, the ongoing conflict was severe enough in the mid-1990s to result in protest, a blockade of the New York State Thruway, violent clashes with police, and years of heavy trooper presence on reservations (Mayer 2013; Porter 1999). Physical confrontations are just one aspect of the struggle; there have been a number of costly and lengthy legal battles between Native nations and New York state over the enforcement of excise taxes on cigarette sales on reservations and multiple attempts at different legislation and regulations. Public, sometimes violent, conflict between Native nations and businesses and state actors over the enforcement of state cigarette taxes on Native lands is not limited to New York. There have been conflicts, cigarette seizures, arrests, and ongoing litigation over state cigarette taxes from states such as Washington, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island over the past few decades. States and Native nations have lost access to revenue from taxes that would likely be billions of dollars by now, if not more. Battles over the enforcement of cigarette taxes for on-reservation sales have at times turned tribal and state officials into bitter enemies.

Figure 1.1 Photograph of Protestor

Quinna Hamby holds a sign during a rally at the Tuscarora Indian Nation near Niagara Falls protesting the state’s attempts to collect taxes on cigarette sales by American Indian businesses to non-Native customers.

Source: Reprinted with permission from AP. David Duprey/AP. September 1, 2010.

Yet the conflicts are only part of the picture. At the same time as these battles endure—indeed, sometimes even in the same states—in other examples, conflict has been very limited or even nonexistent, and tax agreements have been made between Native nations and states under a very broad range of conditions. Tribal–state agreements, their stipulations, and their outcomes have varied widely. Some primarily benefit the state with revenue, other agreements provide for shared revenue, and others allow Native nations to maintain all revenue. All these agreements, however, have sought to reduce the conflict that can arise when states and Native nations do not agree on the state’s ability to enforce the collection of state taxes on Native lands. The most productive and enduring agreements also sincerely recognize and offer a commitment to the sovereignty of both parties involved. In yet other cases, cigarette tax enforcement has simply not been a major issue; either the Native nations have complied with state directives, states have expressly waived their rights to cigarette taxes for on-reservation sales, or the stakes are not high enough for state actors to be concerned with enforcement.

Conflicts such as the situation in New York in 2010 are a result of the complex political challenges that characterize intergovernmental relations between the Native nations within the United States and the 50 states. Cigarette taxes are just one component of a wide range of issues surrounding the practice of Native sovereignty. Certainly, the issue has to do with conflicts over resources, tax bases, and tax revenue. But it is also much more. The dispute over state cigarette tax enforcement between Native nations and states is, at the heart, about understandings and disagreements over Native sovereignty and increasing expectations of intergovernmental interactions in the modern policy era. While much scholarly attention has been devoted to the rise of tribal gaming in the modern policy era, this book argues that there is much to learn about the practices and perceptions of Native sovereignty, the role of economic incentives, and the possibilities and realities of tribal–state agreements through a study of cigarette taxation.

Policy experts, as well as many practitioners from all levels of government, have advocated for tribal–state compacts as a mechanism to support collaborative intergovernmental relations, recognize sovereignty, and prevent conflict, uncertainty over jurisdiction, and lost resources. Other voices argue that institutional state bodies to support and recognize government-to-government relations are key to building sound relationships. Both of these concepts and practices also have opponents, who argue that the Native nations have relationships with the federal government only, not states, and that these agreements or frameworks will diminish tribal sovereignty.

This book evaluates various possibilities for reducing conflict involved in tribal–state intergovernmental relations. I argue that while institutional mechanisms such as tribal–state compacts and state recognition of Native sovereignty with governmental bodies are important, the unique nature of the relationship with each Native nation means that these institutions are far from sufficient to ensure cooperation and positive relationships. Furthermore, if states persist in viewing the issue as economic and regulatory while Native nations see it as one of sovereignty, agreements will be very unlikely and short-lived if they emerge. While they may offer a short-term solution to the immediate problem, unless compacts are built on a real mutual recognition of sovereignty, they will be hard to uphold into the future.

Furthermore, when economic stakes are perceived as high and taxation is perceived as a zero-sum game, cooperation with the state will be very unlikely even if there is a shared perception of the agreement and issue as primarily economic. There must be readily perceptible advantages for both sides to come to an agreement on a compact in a high-stakes situation. These conclusions are important for states and Native nations not only for cigarette taxation but also in looking ahead to relations on other areas of increasing interaction, such as marijuana cultivation and sales.

This book presents an analysis of the intergovernmental relationships between Native nations and states through the particular lens of cigarette taxation. The book moves forward in both chronological and topical fashion to weave the complex story of the United States, Native nations, states, tobacco, and excise taxation. The historical narratives offer the foundation for a quantitative analysis and case studies. The development of the perspectives, expectations, and concerns of the various actors involved provides much greater insight into why state cigarette taxation can become so contentious and what measures can help states and Native nations move from conflict to cooperation.

This chapter moves on to offer an overview of various terms and concepts that are important for navigating the book. For those unfamiliar with the history or legal status of Native nations in the United States, the next two sections, “Increasing Tribal–State Intergovernmental Relations” and “Definitions: Native Nations and Sovereignty,” will be very helpful in offering a framework and important terminology for the rest of the book. The final substantive section of the chapter provides an overview of the main ideas and layout of the rest of the book.

Increasing Tribal–State Intergovernmental Relations

Traditionally, studies of intergovernmental relationships in the United States have been discussed as a matter of federal and state relations or at times of local and municipal governments. However, Native nations are an important aspect of intergovernmental dynamics as well. As of July 2016, there were 567 federally recognized American Indian tribes that had a “unique legal and political relationship” with the federal government as laid out in the Constitution, treaties, and laws (Bureau of Indian Affairs 2017). These Native nations, which are recognized in treaties or through federal action as distinct political entities, have a legal and historic nation-to-nation relationship with the federal government. The reality of a nation-to-nation relationship has been frequently abused and misunderstood by the federal government, but it remains the foundation for interactions between Native nations and the federal government and Native arguments for sovereignty and self-determination.

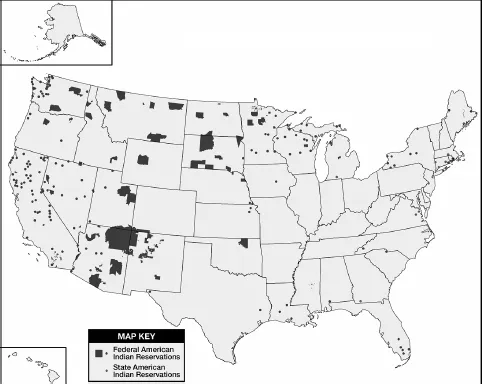

Most of these Native nations also have legally recognized territories, often referred to as Indian reservations. As can be seen in the map in Figure 1.2, these Native territories are scattered across the country. Because many of the Native peoples on the East Coast were forced out or forcibly moved westward early on in American history, most reservations are in the western half of the country. In addition, some states recognize Native nations and state reservations. Native nations that are state-recognized only have a particular state–tribal relationship determined by that state and do not have the same nation-to-nation legal benefits of federally recognized tribes. This work is largely concerned with federally recognized tribes but in some cases will also note the role of state recognized tribes.

Figure 1.2 United States Census Map of American Indian Reservations

Source: United States Census (2017).

Despite a formal nation-to-nation framework with the federal government, Native nations increasingly interact with other levels of governments, particularly state governments (Bays and Fouberg 2002; Corntassel and Witmer 2008; Wilkins 2016). These intergovernmental relationships between Native nations and states have developed over time, with historical roots as early as the country itself. More recently, the federal government has shifted policies toward an era of self-determination, which has increasingly devolved authority both to Native nations and to states. Because of this, tribal–state relations have become a growing issue in the modern era of policy making, with tribes taking on increasing capacities of self-determination at the same time as states are seeking to assert authority over a range of policies. At the core of the relationship is the negotiation and recognition of the sovereignty of each entity, the tribe and the state.

Scholars and a range of political experts have offered a framework of various explanations and suggestions for what can support positive tribal–state relations. In recent years, some states, scholars, and Native leaders alike have supported negotiations and the development of state–tribal compacts on specific issues to clarify jurisdiction and promote cooperation (Clarkson and Sebenius 2011; Cowan 2005; Mack and Timms 1993; Mayer 2013; Murphy 2011; Tsosie 1997; Wilkins 2016). Some states have established legislative or administrative bodies with specific oversight of Native affairs, and this has been explored as a mechanism for reducing conflict (DeLong et al. 2016). In both cases, some institutions are far more carefully designed and active than others, which also has effects on how much they are able to influence tribal–state relations. This work offers an evaluation of the role of these various institutional structures and agreements and how well they reduce conflict in the area of cigarette tax enforcement.

Social, political, and economic contexts and histories can also set the stage for collaborative or conflictual relationships. Broader representation and legislative influence of Native peoples in a state may have influence over tribal–state relations. In many states, Native peoples are a very small percentage of the population with little representation in state government, but in a few they do have a significant presence, which may then influence state policy and action. Past policy experiences and the larger political environment may have influence as well. States that have a long history of enforcing other policies in Indian country may have different expectations and relationships than those states in which there is less jurisdictional overlap. Furthermore, in the case of tax policy, there are serious economic interests at stake. Whether economic “losses” are real or imagined, states with large potential losses are likely to act differently than are those states in which the economic stakes are smaller.

Cigarette taxes offer a contemporary and interesting opportunity to assess tribal–state intergovernmental relations and possibilities and evaluate proposed mechanisms for promoting collaborative and positive relationships. Much of the recent work on tribal–state relations has focused primarily on gaming, with comparatively little on other topics. Taxation on activities on a government’s territory is an integral element of sovereignty. Tax jurisdiction, therefore, is a central and necessary concern—and a very high-stakes issue—for both Native nations and states. Tobacco and its use are deeply tied to Native histories and cultures and have a very important role in colonial history and the origins of the new country. Furthermore, the taxation of tobacco has been an important area of tax policy since early in the nation’s history. There are many elements of the story of tobacco taxation that can help us better understand the trajectory of intergovernmental relations and to begin to evaluate possibilities and mechanisms for positive relations that may have effects on a much wider range of intergovernmental interactions.

Definitions: Native Nations and Sovereignty

Chapter 2 offers a much more comprehensive discussion of the development of tribal–federal and tribal–state relations, but it may be helpful for some readers to start with a basic definition and overview of important concepts, such as “nation” and “sovereignty.” Mayor Bloomberg’s remark, which echoed the era of cowboys and Indians, war, armed conflict, and the historical genocide of American Indians, was certainly “insensitive” (Deloria 1998). It reflects much more than a lack of cultural respect and awareness, however. The conflict over state excise taxes for transactions on reservations is a manifestation of a much larger issue: that of Native sovereignty. Native sovereignty has been at the center of conflict between Native nations, the federal government, and states for centuries. When any entity, state, federal, or Native, has a different understanding of sovereignty and jurisdiction from that of the other entity with which they are involved, conflict arises. Most often in modern tribal–state interactions, this occurs when states do not recognize the nationhood and sovereignty of Native nations.

Native Nations

The term Native nations is used throughout the book to refer to the indigenous peoples of the United States. The choice of terms used is a complex one. Generally, it would be preferable on all counts to use the title that indigenous people call themselves, such as the Anishinaabe, which is the name that those who are also referred to as the Chippewa or Ojibwa in the United States and Canada call themselves. However, many portions of this work refer not to a single group but to policies or actions tied to a number of indigenous peoples at once. Federa...