This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Originally published in 1988. Europeans want a better environment. Increasingly, too, they are demanding the products, services, legislation and policies that will provide it. Green Pages reveals what Europe's environmentalists plan to do next and how environmental pressures will threaten major markets – and at the same time opens up new opportunities for business, investment and employment. Green Pages is a fantastic reference source for green enterprise, and will be of interest to students of environmental economics.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Green Pages by John Elkington, Tom Burke, Julia Hailes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

SECTION 1

Targeting the Green Consumer

It’s not enough to slap a green label on a product and wait for the customers to roll in. The markets for green products and services need to be properly researched - and effective marketing is as essential in the emerging green economy as in any other business sector.

Market research, if you believe Anita Roddick of the Body Shop chain of stores (page 70), is like ‘looking in the rear-view mirror.’ You are looking at what has gone. No enthusiast for market research, her views are worth listening to, since she turned a £4,000 overdraft in 1976 into a public company with profits of £7.9 million in 1986–87. But not everyone has Anita Roddick’s business flair.

Green Cuisine, for example, was an excellently produced publication focusing on health foods, in addition to covering many parts of the emerging green economy. Launched with much enthusiasm, and to considerable critical acclaim, it never really caught on. It shut up shop in 1987.

In a period of extremely rapid change, with consumer preferences increasingly shaped and reshaped by environmental concerns, it can be extremely difficult to predict which existing markets are going to be affected, let alone what new market opportunities may open up. Those of us without the Roddick touch cannot afford to forget the importance of well-targeted market research and marketing.

The opportunity spotters

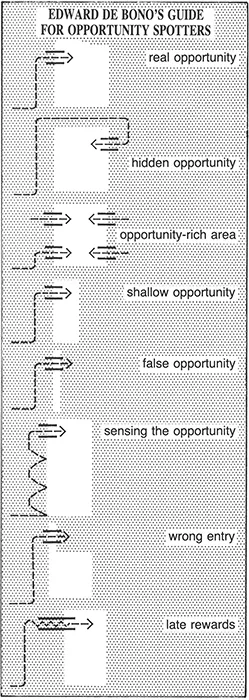

While there is an entire industry which describes what it does as ‘market research’, lateral thinker Edward de Bono prefers to think in terms of an ‘opportunity search.’ He points out that many prime commercial opportunities have been totally overlooked by companies which have too narrowly focused on a particular definition of what business they were in.

For the small sum of $100,000, he recalls, Alexander Graham Bell offered to sell his telephone patents to the giant Western Union Telegraph Company. ‘He had no choice,’ Dr de Bono noted, ‘because his backers had run out of funds. Without any hesitation, William Orton, then President of Western Union, turned the offer down.’

Most industrial executives, de Bono argues, ‘are trained for maintenance, for efficiency and for problem-solving. Opportunity thinking is quite different. An opportunity is not there until after you have seen it. Seeking, recognising and designing opportunities requires a different set of thinking skills. These are skills of perceptual and conceptual thinking; the skills of creativity and lateral thinking.’

We are all surrounded by opportunities, most of which will be seen only if we go out and look for them. To help steer his clients towards some of these opportunities, de Bono has distinguished between many different types of opportunity - some of which are highlighted on page 57. ‘In a corporation,’ he stresses, ‘the search for opportunities should be everyone’s business, for everyone is directly concerned with what tomorrow will be like.’

No-one doubts that new commercial opportunities are opening up in the green economy - but how can one spot them? Edward de Bono recommends what he calls ‘opportunity thinking’. Contributors, including Anita Roddick of the Body Shop (page 70), look at the way in which green products and services can be developed and sold.

As later sections of Green Pages show, the green economy is bursting with what de Bono would describe as ‘real opportunities’ (e.g. pollution control, energy efficiency, organic farming or ethical investment), ‘hidden opportunities’ (e.g. the buying power of the Green Consumer) and ‘opportunity rich areas’ (e.g. green publishing or tourism).

It is also possible to think of examples of ‘shallow’ or ‘false’ opportunities - and of markets where established companies or environmental entrepreneurs have made a ‘wrong entry.’ It is all too easy to misjudge the rate at which markets which are driven by regulation or ethical concerns are going to develop. Companies which select markets with a strong political dimension, like the catalytic converter market in which Johnson Matthey has long been a leader (page 116), may find that the slow pace of political progress injects a good deal of uncertainty into the market. But environmental entrepreneurs should not give up too soon: some areas, such as renewable energy, are likely to prove not ‘wrong entry’ markets but areas where they should be thinking in terms of ‘late rewards’.

Gauging the market

Once you have a product or service which you think is going to meet a real market need, the next stage is to come up with a properly targeted marketing strategy.

Not long ago, marketing was left to second- or third-rate managers, but the 1980s have seen a radical re-evaluation of the importance of marketing people. Their patch takes in market research, sales promotion, advertising, public relations and general management jobs with a marketing bias,’ explains Dorothy Venables, a senior consultant with Hoggett Bowers Search and Selection, ‘in fact, every discipline that boosts the selling of goods and services.’

The golden rule of market success remains the same: you need a detailed knowledge of what the customer really needs and wants. If you are selling consumer products, perhaps you should be talking to a specialist research company like Taylor Nelson Applied Futures (see page 52). If you operate in the environmental equipment market, on the other hand, you may want to buy a market assessment produced by a company like Frost & Sullivan.

The global market values you will be presented with will often sound impressive. Frost & Sullivan forecast in 1986 that the West European market (in a total of 18 countries) for all the mechanical equipment used in water and waste treatment, worth $1.3 billion in 1985, would reach $1.8 billion by 1995 (in constant 1985 dollars).

Such global figures are of little value on their own, however. You need to know who will want to buy what sort of equipment when - and at what sort of price. In this area, at least, West Germany turns out to be the largest national market, with about a 25% share, followed by France and the UK with fairly equal but lower shares, and then Italy. Taken together, these four countries represent two-thirds of the European market, leaving the remaining third spread across the remaining 14 countries, including Sweden, Norway, Finland, Austria and Switzerland.

But it may be a mistake for a company wanting to move into this area to simply target the biggest market: it may already be sewn up by well-established producers. Another tactic is to look for the national markets whose share of the overall market is likely to grow most rapidly. This might then place the spotlight on such countries as Italy, Spain, Belgium and Greece.

The next stage would be to look at specific technologies and applications which are most likely to produce buoyant demand. Frost & Sullivan, to stick with this particular example, expect rapid growth in demand for equipment for the tertiary processing of liquid effluents, for the chemical filtration of fresh water and for waste sludge dewatering. While public sector demand may tend to come from the need to increase treatment capacity as populations expand and older systems are upgraded, industrial demand is more likely to be driven by such factors as the need for ever-cleaner production processes or the introduction of new effluent controls.

It would also be a mistake, however, to imagine that such markets are ready and waiting to embrace innovative new technologies. Some are, of course, but the water and waste treatment sectors tend to be rather conservative in their approach to innovation, not least because of the political sensitivity of public health and the sheer financial impact of any failure to provide a system which works to increasingly stringent standards.

Sean Sprague. Panos Pictures

Market forces brought these tuna to Tokyo . . .

Since there is no point in biting off more than you can chew, the next stage might be to ask which equipment users are likely to be easiest to sell to - either because you already have a track record with them or because their needs are not unduly sophisticated. As in most areas of business, it is important to start out by picking areas where you have a reasonable chance of succeeding and then build on that success.

Fingers on the pulse

Once you have broken into a market, particularly in the green economy, it is essential to keep a close watch on the way the market is developing. There are a growing number of options here, but it makes sense to subscribe to an information service which regularly monitors the regulations, decisions and other factors likely to have a major market impact.

Many companies, for example, now subscribe to the ENDS Report (page 34), to keep their finger on the environmental pulse. Other options include linking up with some of the environmental networks which are now emerging or joining one or more of the relevant environmental organisations.

There is also a growing interest around Europe in a new approach to public relations, in which the process of communicating with internal and external constituencies becomes more important than any single PR event (page 218), and environmental organisations unquestionably now rank high on the list of priority contacts for any self-respecting PR company or professional.

As those organisations zero in on product after product, technology after technology, company after company, it will often be necessary to provide intensive market support. In some cases, however, the product may simply be beyond support. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) have been a prime example of a product reaching such a point of no return. It is vital to be able to recognise such a transition point, since spending more money on research on the environmental impact of such a product may simply be a diversion of scarce resources.

Once found in all kinds of equipment, including washing machines, aircraft and computers, nonflammable PCBs were also used for cooling and insulating electrical equipment, and as hydraulic fluids, cutting and lubricating oils, and plasticizers (in paint, copying paper and printing ink). Even when the environmental and health problems associated with these ‘dream’ products began to emerge in the 1960s, however, they were not banned outright. Although the member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) banned the use of PCBs in many applications in 1973, for example, they could still be used in ‘closed’ systems - such as transformers, industrial heat transfer systems and hydraulic equipment in underground mines.

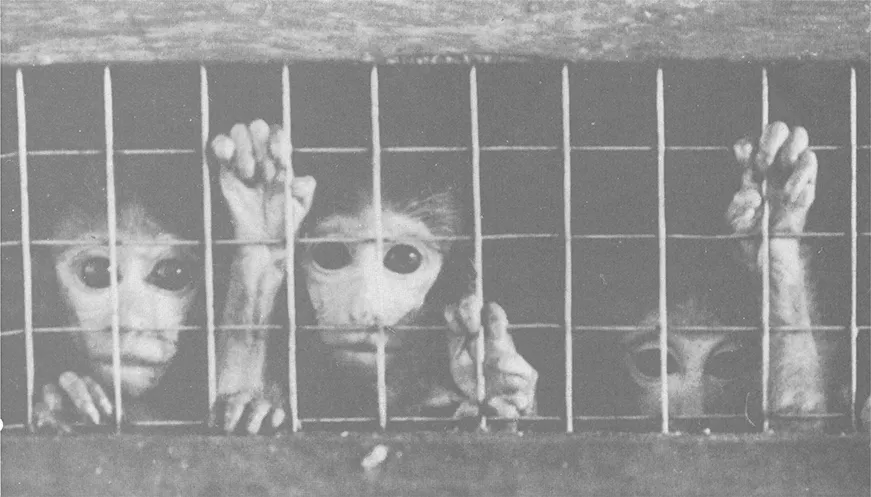

WWF International

. . . and these smuggled macaques to Belgium.

Less than seven years later, PCB manufacturing had fallen by 60% in the OECD area and its use had practically stopped in 10 out of the 24 OECD member countries. The final stage came in 1987, when the OECD Council imposed a total ban on PCBs. The manufacturing, importing and exporting of PCBs and of any equipment containing or requiring PCBs must cease from 1 January 1989.

In other words, it took 14 years to achieve a total ban on this range of hazardous chemicals. During that time, the producers and suppliers came under increasingly stringent controls and were required to restrict the marketing of their products to a rapidly shrinking number of approved applications.

In hindsight, perhaps it would have been better to go for a total ban much earlier on, but the situation is rarely simple enough to permit such action. Many products - like the chlorofluorocarbons implicated in atmospheric ozone depletion (page 88) -have major advantages which offset, to a greater or lesser extent, their environmental and health implications. Another example of a product which has come under fire from environmentalists is the thermoplastic PVC.

A friendly plastic?

The perfect plastic. That, in a nutshell, was what the environmentalists who attended the European Conference on Plastics in Packaging in 1986 were looking for. Why, they asked, could industry not make do with just one plastic, a plastic which met every need without causing environmental problems in the process?

The answer was not long in coming from the industrialists present: there is no such plastic. Whatever the facts of the matter, however, the environmentalists came to Brussels because they believed (and believe) that plastic packaging causes real environmental problems. From an industrial point of view, this type of environmental challenge is always unwelcome, but particularly so when the product under threat does not enjoy a buoyant market. PVC is one such product and the plastics industry has therefore been worried by the environmental question marks which have clustered around what it sees as one of the most versatile and cost-effective thermoplastics.

Apart from early concerns about the health impact of vinyl chloride monomer, the PVC industry has also had to respond to other issues, including worries about the safety of PVC in fires, the possible contamination of food by plasticizers in PVC cling films, and the contribution of PVC packaging to the littering of town and country. The latest conc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface to the 2017 edition of Green Pages

- Preface: Stanley Clinton-Davis

- Contents

- Perspectives: List of contributors

- List of advertisers

- Introduction

- The Business Environment

- Greener Growth

- 1. Markets

- 2. Design

- 3. Research

- 4. Computers

- 5. Pollution and Waste

- 6. Energy

- 7. Farming and Forestry

- 8. Urban Renewal

- 9. Tourism

- 10. Health

- 11. Money

- 12. Media and Publishing

- 13. Advertising & Public Relations

- 14. Careers and Education

- Into the 1990s

- Follow Up

- Index