In July 2013, I presented part of my research on sampling and remix at an international summer school in Hamburg entitled “Repeat, Remix, Remediate: Modes and Norms of Digital Media Repurposing.” The nature of the questions and debate that followed strongly reaffirmed my belief that remix and sampling are widely misunderstood concepts and that such confusion can detrimentally affect progress in theorizing and discussing this kind of work. By then, I had already carried out extensive research into the area, but my discussions with other experts on remix that week only served to strengthen my resolve. To date, I have had the privilege of researching remix in a number of different regions, including the USA, Europe, and the Middle East, as well as co-editing two volumes on remix studies, which have enabled me to see first hand how people from different cultures and societies tend to understand and respond to it.

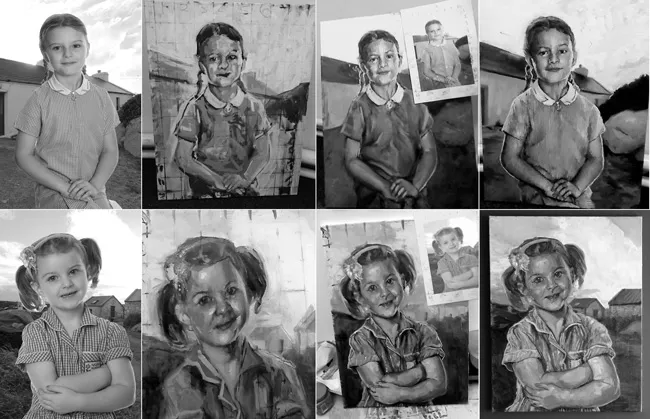

For me, it has always seemed apparent that remix can only be considered remix if it uses samples; however, over the past number of years, a trend has emerged among remix scholars and practitioners, whereby the term has been used to encompass much more than that. Being a musician myself, as well as working and teaching in the areas of graphic design and digital media production, the distinction between making something original and making a remix is very clear to me. A few years ago, I commissioned an artist to paint a portrait of my daughter for her birthday. I provided the artist with a photograph of my daughter and another photo of our family holiday cottage to be used as a background. The artist produced a portrait using oil paints on canvas, based on these two photographs. The end result is a newly produced work.1 As part of her process, the artist “photoshopped” the two photos I gave her together, cutting out the image of my daughter and placing it in front of the image of the cottage. This photoshopped collage was used as a reference image for her painting. One of these images is a remix; the other is not.

Clearly, the photoshopped collage is a remix because it uses elements of the actual photographs as samples, combining them together in a new way to produce a composite image from these preexisting images. The painting, however, is not a remix, as it is composed of nothing more than paint, each brush stroke carefully applied to the canvas in a uniquely personal way by the artist. The painting is certainly intertextual because it is inspired by the collage—there is clear evidence of aesthetic emulation—but it is not a remix because it does not actually use any sampled elements in its composition. It is a work that has been newly produced by the artist. Incidentally, I was so pleased with the final portrait, I had the artist paint another one of my youngest daughter for her birthday, using the same intertextual process (Figure 1.1).

Unfortunately, there has been a tendency in recent discourses on remix to inaccurately define intertextual works, such as these paintings, as remix. Every creative work is arguably inspired in some way by something else, but this does not mean that it is a remix. If every creative act is a remix, then nothing is a remix and this is simply not the case. As will be shown in this chapter, medium specificity distinctions have always been important for the theorization of media artifacts as new technologies emerged enabling different media forms to exist. Thus, it is essential to demonstrate what differentiates remix from other forms, especially related intertextual activities with which it is often confused.

1.1 Painting vs. Poetry: An Age-Old Debate

The sister arts of painting and poetry, representing the historically dominant forms of the visual and literary arts, respectively, have been central to the discussion of medium specificity since the concept was first considered. Conceptual thought on the relationship between media forms has undergone several significant shifts of consciousness over time. Simonides, Plutarch, and Horace highlighted the similarities between painting and poetry, while da Vinci, Lessing, and Greenberg focused on their differences. Mitchell returned to a more balanced view, in response to Greenberg’s abstract extremism, while Jenkins and Manovich have brought us full circle, with a perspective that focuses not only on the similarities between digital media forms, but also their synthesis, hybridity and modular, interchangeable, and remixable nature.

More than two millennia ago, Horace2 conceived of the phrase “ut pictura poesis” (“as is painting, so is poetry”). Horace’s ideas were directly informed by those of Simonides of Ancient Greece, who claimed in the sixth century BC that “painting is silent poetry and poetry is painting that speaks.”3 In Renaissance Italy, Leonardo da Vinci4 argued that painting is superior to poetry because it deals with the similitude of actual forms in order to represent them, while poetry can merely describe forms, actions, and places in words. At the height of the German Enlightenment, Gotthold Lessing5 took issue with Horace’s infamous analogy, arguing that painting and poetry are inherently different art forms because each belongs to a different “medium.” Painting belongs to the medium of space, he claimed, since it is a visual, spatial art, while poetry belongs to the medium of time, since it is a verbal, temporal art.

In twentieth-century America, Clement Greenberg compared painting, particularly abstract painting, to music, which he claimed was inherently pure because it cannot be adequately described or represented in any other media form than its own. For Greenberg, it was wrong for painting to attempt to emulate ideas better expressed in poetry or literature, as painters and sculptors had begun to do in the seventeenth century.6 Greenberg’s extreme ideas were contested and ultimately rejected by W.J.T. Mitchell7 when he claimed that there is no such thing as a purely visual media artifact, nor purely textual, aural, or tactile objects. What we refer to as visual media, such as painting, photography, film, and television, all involve the other senses as well as the optical. All forms of media are not specific to any one sense but rather are “mixed media,” combining many elements and features that can be perceived by multiple human senses in different ways. Drawing from Marshall McLuhan,8 Mitchell felt that the specificity of media was a question of specific “sensory ratios,” which are embedded in practice, tradition, experience, and technical inventions.

Henry Jenkins argues that it is no longer important or relevant in the digital age to focus on marking the borders between media that separate them.9 Instead, the focus should move to exploring the spaces where different media forms intersect, overlap, and mix together to produce hybrid forms. Jenkins criticizes previous theorists of medium specificity, especially Greenberg, as he claims that historically such theories have moved from being useful descriptions of the properties of a specific medium, to limiting prescriptions for what the aesthetics of those specific media should look like. Lev Manovich claims that all previously separate media forms have lost their specificity and now exist in one all encompassing “metamedium,” enabled by constantly changing digital technologies and software production environments.10 While once we may have perceived material differences between painting and poetry, when they are represented as digital images and text, the elements of both are reducible to interchangeable modular blocks, which can be remixed into hybrid forms. For Manovich, the specificity of new media is represented by “deep remixability” and its aesthetic is defined by hybridity. Not only can we now remix the content of previously separate media forms, but we can also remix the techniques of production, working methods and ways we represent and express that content.

What these examples suggest is that the human concern with the nature of media and the relationship between different media forms has been an important consideration since first we fixed our ideas in a tangible medium of expression, right up to the present day. The differences and similarities in comparing new creative practices and their outputs as they emerged, parallel to advancements in media technologies, have been and remain an important theoretical project for those seeking to better understand a particular form of creativity in relation to its counterparts.

We can clearly see from these examples that there is a significant degree of disparity evident in terms of the theoretical underpinnings of what exactly constitutes a “medium” or “media.” Mitchell considers the human senses the primary differentiator, distinguishing between optical, aural, and tactile media. Lessing focuses on immaterial concepts to distinguish between what he refers to as the medium of time and the medium of space, to which poetry and painting, respectively, belong. Horace, da Vinci, and Greenberg identify the differences and similarities of art forms by distinguishing between the medium of painting and the medium of poetry. Jenkins considers the distinction between old media and new media, and Manovich focuses on the concept of a “metamedium,” which brings all previous media forms together through a common reliance upon digital software. There appears to be no consensus in terms of the underlying assumptions about media that inform the ideas developed by these authors. However, we can see that all of these factors—the human senses, space, time, and technology—are important aspects that need to be considered in order to arrive at a full understanding of medium specificity.

For the purposes of this chapter, the term “medium” refers to a system through which content can be communicated between two or more parties. In practice, there are three such systems in operation, which enable different forms of communication between people: interpersonal media (one-to-one), mass media (one-to-many), and new media (many-to-many).11 Each medium requires different technologies to function; for example, interpersonal communication does not necessarily require any—one person can tell another person a story, poem, or joke; an artist can paint a portrait of someone and then show them the painting. Mass communication, howev...