This is a test

- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reconceptualising Film Policies

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume explores and interrogates the shifts and changes in both government and industry-based screen policies over the past 30 years. It covers a diverse range of film industries from different parts of the world, along with the interrelationship between different localities, policy regimes and technologies/media. Featuring in-depth case studies and interviews with practitioners and policy-makers, this book provides a timely overview of government and industry's responses to the changing landscape of the production, distribution, and consumption of screen media.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Reconceptualising Film Policies by Nolwenn Mingant,Cecilia Tirtaine in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Traditional Film Policy Paradigm

Introduction by Nolwenn Mingant and Cecilia Tirtaine

In 1944, as the Argentine cinema golden years were coming to an end and screens were flooded by US films, the government made its ‘first institutionalised film policy’: a quota guaranteeing screen time for Argentine films (Falicov 2007, 27). The quota was a ‘nationalistic move to protect the Argentine film industry, but it was also most likely in retaliation for the embargo on raw film stock set by the United States’ (Falicov 2007, 28). This embargo on raw film stock had been decided by the US government in 1942, officially to protest the trade and diplomatic relations that Argentina maintained with the Axis power and, unofficially, to weaken this strongly competitive film industry. In the film dispute that opposed them, both sides had chosen an interventionist approach based on the defence of a national interest understood as a mix of economic, cultural and political components.

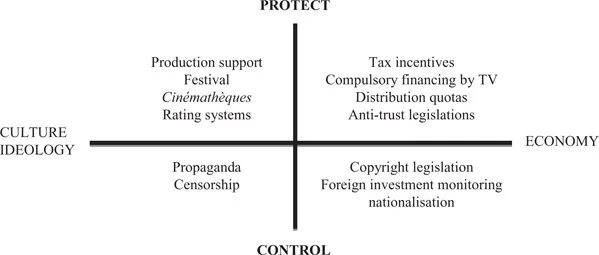

In his study on British colonies in the Pacific, Newman seeks to untangle this mixed nature by identifying three ‘policy imperatives’ underlying governmental action: safety (which includes building codes as well as censorship), social control and development (e.g. education and propaganda) and economic considerations (e.g. subsidies, taxation and tariffs) (Newman 2013, 41). This model is interesting not only as it encompasses both concrete and ideological measures, but also for its inclusion of the idea of control. In this volume, we propose to visualise the tensions that have traditionally underlain film policy through two axes (Figure 1.1). The horizontal axis represents the rhetoric used to justify state intervention, with economic considerations at one end of the spectrum and cultural/ideological arguments at the other end. The vertical axis represents the nature of state intervention, with a gradation from protection-oriented to control-oriented ones. Protective measures can, for example, be implemented in the name of culture (film production support to defend cultural diversity) or to save the national economy (establishment of screening quotas). But the protective approach to the film industry can also morph into more control-oriented measures, such as the nationalisation of production and distribution. Depending on the political and economic situation, both at home and internationally, a given state will tend to favour one of the quadrants.

Figure 1.1 The traditional film policy paradigm.

Another element that influences the nature of film policy is the level of state intervention. During the Cold War, two models were particularly opposed: the strongly interventionist nature of the Soviet State and the economically liberal approach of the United States. In the international market, Sovexport epitomised a hands-on type of approach, while the Motion Picture Export Association symbolised the US hands-off approach. Appearances are deceptive, however, as the US did put its full weight behind its film industry not only by sending films to the newly liberated European territories after World War II, but also by providing information and help around the world through their embassies or by keeping the film industry’s interest in mind during trade negotiations. The traditional film policy paradigm that has guided governments since the beginning of cinema thus rests less on a clear-cut opposition between interventionism and laissez-faire than on the degree of intervention chosen according to the economic and political context. Furthermore, over the decades, film policy cultures have tended to become entrenched. Historical institutionalism studies have conceptualised this through the notion of ‘path dependency’, according to which ‘past policy has an enduring and largely determinate influence on future policy’, hence the existence of ‘characteristic national “policy styles” or national “regulatory styles”’ (Gibbons and Humphreys 2012, 16). Governments’ leeway will, for example, be conditioned by their countries’ inherited administrative structures, as is expressed by the concept of ‘institutional parity’: in a ‘low institutional parity’ context, state branches in charge of culture are subordinates to economic branches, while they dominate in ‘high institutional parity’ context (Flibbert 2007, 101–2). The current intervention of the Russian state through the financing of propaganda programmes on public television network Rossiya One (Brassard 2016), and the intervention of the US states through tax incentives and US agencies such as the CIA or the Pentagon through advice and material loans (Valantin 2003; Jenkins 2012; Peltzman 2013) are thus to be read in view of these countries’ entrenched national film policy culture and structures.

Another lesson of the 1944 quota battle between Argentina and the United States is the centrality of ideology. Even when economic considerations are at play, film policies are often also about the national identity a state wants to promote at home and abroad. During the second half of the 1940s, the Perón administration had ‘transformed the film industry into a bastion of government propaganda’ (Falicov 2007, 29), while in the post-World War II era, the Hollywood film industry was trumpeting its role of ‘salesman’ of America’s consumer society and democratic culture around the world. While economic discourse tends to dominate today, control over the representation of national identity is still very much a central tenet of film policy. Hence, the soft power battle waged in the international area. Although Nye underlines that soft power is usually best developed through non-governmental action (Nye 2002, 11), states today actively use film and media policies to try and harness this power of attraction. The contributions in this first section explore how the traditional film policy paradigm plays out today as each state mobilises and adapts historical tools to best defend their national interest.

References

Brassard, Jeffrey. 2016. “Putin’s Lumbering Giant: State Television and Ontological Security in the Putin Era.” SCMS Annual Conference, Atlanta, 2 April.

Falicov, Tamara. 2007. The Cinematic Tango: Contemporary Argentine Film. London: Wallflower Press.

Flibbert, Andrew. 2007. Commerce in Culture: States and Markets in the World of Film. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gibbons, Thomas, and Peter Humphreys. 2012. Audiovisual Regulation under Pressure. London: Routledge.

Jenkins, Tricia. 2012. The CIA in Hollywood: How the Agency Shapes Film and Television. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Johnston, Eric. 1957. “Hollywood: America’s Travelling Salesman Sold America into Mass Production.” Vital Speeches of the Day, 1 July.

Newman, David. 2013. “Resisting Hollywood? A Comparative Study of British Colonial Screen Policies in the Interwar Pacific: Hong Kong, Singapore and New Zealand.” PhD diss., Simon Fraser University.

Nye, Joseph. 2002. The Paradox of American Power. New York: Oxford University Press.

Peltzman, Daniel. 2013. “The Film and Television Tax Credit and Its Impact on the California Motion Picture Industry.” Presented at the 2013 CinEcoSA Conference, “Film and Television policies in English-Speaking Countries,” Université Paris 8, Paris, 25 October.

Valantin, Jean-Michel. 2003. Hollywood, le Pentagone et Washington. Paris: Autrement Frontières.

1 ‘France needs to position itself on the global media map, as a cultural reference and a production centre’

An interview with Stephan Bender (North-East of Paris Film Commission/ Film France)

Film policies are not solely developed by state agencies, but are also devised and implemented by organizations known as ‘quasi-autonomous non-governmental organizations’ or ‘quangos.’1 One such organization benefitting from state subsidies and fulfilling state missions in France is the Pôle Média Grand Paris. In 2014, Stephan Bender, head of the Commission du Film de Seine-Saint-Denis (North East of Paris Film Commission), thus presented his organization.2

What is the Pôle Média Grand Paris?

The Pôle Média Grand Paris is a media cluster whose goal is to provide tools and services to build a stronger media industry. It consists of companies, universities and public authorities. At the turn of the twentieth century, local authorities realised that a strong film and TV industry had established in the north-east of Paris. It is a poor area, where land is not expensive, so film companies had simply crossed the ring road. A few kilometres from the capital, you found soundstages, TV sets, all the facilities to produce films. The local authorities felt they had to do something to make sure they stayed, and in 2001 they created the Pôle Audiovisuel Nord Parisien (North-East of Paris Audiovisual Pole) association. It was a gamble. Its focus expanded to the north-east of Paris and Paris in 2006. Since 2011, it also includes the ‘Grand Paris’, quite a vague notion meaning Paris and the area around it.

In 2011, it was renamed the Pôle Média Grand Paris (Paris-area Media Pole), as film and audiovisual are now subsumed in the term ‘media’. There are now eighty-four mostly small- and medium-sized companies; twelve research centres or film schools; and seven public authorities (Seine-Saint-Denis département, Plaine Commune, Est Ensemble, Ile-de-France region, ministries). A first source of financing is two conurbation authorities: Plaine Commune and Est Ensemble, with 400,000 inhabitants and about ten towns each. The département (1.2 million inhabitants) and the region also subsidise us. And the state provides special financing as we are now labelled as a cluster. So we have different financing for different missions. Some are strongly connected to the territory we are working on, and others connected to what we are doing, that is a cluster, connecting companies and research centres.

When and why was the Commission du Film de Seine-Saint-Denis created?

When the Pole started to be active, in 2003, its first decision was to create the Commission du Film de Seine-Saint-Denis. At that time, it was the first film commission in the Paris area. The city of Paris had had a film office for about fifty years, essentially to deliver shooting permits. It was not really a film commission. The Region Ile- de-France, the big area around Paris, had not yet decided to create its own commission. So creating the North-East of Paris Film Commission was really something new. In France, most of the shootings take place around Paris, so, until 2003, no one thought it was useful to attract shootings there.

The Commission was created to generate economic, media and cultural impacts. The economic impact is the direct benefits for the territory: shootings mean money spent in the location and especially more employment for the French film personnel who usually live north of Paris. This is what our remit is and what our subsidies are linked to.

The second goal is the media impact. As I said, the Seine-Saint-Denis is a poor district. The media often show the French suburbs (banlieues) as a dangerous place filled with crime. It’s not true. It’s a cliché. Our goal is to bring the area on screen, not on the TV screens, those showing cars burning and young people doing drugs, but on the big screen, with Hollywood stars. The idea is to show the media and the audience that the Seine-Saint-Denis can be something else than what they are used to seeing.

The third impact is cultural. Some films become part of the culture of a place. L’Esquive, a French film by Abdellatif Kechiche, was shot a dozen years ago in the Franc-Moisin neighbourhood in Saint-Denis, a place usually associated with crime. But it was a wonderful film showing young people learning plays by Molière, an eighteenth-century French playwright, in the French language of the time. When you see the film, you can see the area as it was at the moment of shooting. When you talk to local inhabitants, they are really proud: this movie has become part of their culture.

Can you describe the Commission’s activities?

As the other film commissions around the world, we offer free services to audiovisual professionals. The most important part of our job is to make connections between the production team and the locations. Very often, the place imagined in the script simply does not exist. For example, how to recreate a nineteenth-century hospital close to Paris and for a reasonable cost? This is what the location managers and the film crews are looking for. In the north-east of Paris, there are very diverse locations – a thirteenth-century building transformed into a university, a well- preserved 1960s psychiatric hospital, interesting natural landscapes – all of that five kilometres away from Paris. We strongly rely on our network of films professionals – location scouts, line producers and location managers. It’s vital that line producers are French. Currently, we are building a picture database of locations, to create awareness. Our goal is not to give producers what they know they will find in Seine-Saint-Denis, but to show them what they do not expect but that they are looking for.

The Commission also helps the locations to become film-friendly. We’re helping them to understand what the film crews are expecting and how they could work to be the most efficient for the benefit of both parties – for example not creating disturbance. We also work a lot with cities. They give shooting permits, but they also need to get advice on what the film crews are really looking for. The connection between the people who are looking for location and the locations in the north-east of Paris is our first mission, but we also participate in promotion events at international markets, such such as the AFCI Locations and Global Finance Show,3 the Ile-de-France Location Expo in Paris and the Cannes Film Festival.

We keep ourselves informed of Hollywood projects looking for a location through Film France, the network of the forty film commissions around the country. Nowadays, we handle 100 projects a year – movies, series and advertising. Let me tell you the story of two of these films. Six or seven years ago, Eric Rochant wanted to make a film in a middle school, the story of a gangster hiding from the cops by posing as a teacher.4 It ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I The Traditional Film Policy Paradigm

- PART II The Film Policy Power Struggle

- PART III The Film Policy Tangle

- PART IV (Re)Inventing the Film Policy Paradigm

- List of Contributors

- Index