![]()

1

Architecture and painting: the biological connection

John Onians

We all know that artistic activities such as architecture and painting have common origins in the brain. After all, all the visual arts involve the shaping and/or transformation of some material by the hand, guided by the conscious mind which constantly checks the effects produced through the supervision of the eye, and we are happy to celebrate in a general way the role of neural connections in all this. What we often neglect, however, is the extent to which such artistic processes rely on linkages between the hand and the eye which are beyond the control of consciousness. These linkages involve both the neurons and networks in the outer cortex, which allow the eye and the hand to function separately, and the lower parts of the brain, including the limbic lobe, the basal ganglia and the thalamus, through which the activity of the cortex is integrated with the body’s overall survival system. These upper and lower areas of our brain not only govern most of our behaviour without our needing to think about it, they also, without our knowing, influence our actions even when we think we are in conscious control. Although these areas may seem too much a part of our animal nature to be included in discussions of our higher activities, their operations are so essential for everything we do that they should in fact be familiar to any student of the humanities. For art historians their study is particularly important, since the areas involving the eye and the hand are not only among the largest, they are also the best understood. In the context of the present enquiry their study is especially relevant since they hold vital secrets about the links between architecture and painting, links in terms of both the making of and the response to work in these fields. It is these groups of networks which make the co-ordination of visual attention and motor activity possible in the first place.

It is thus with the neurophysiology of these areas and with the neuropsychology, that is the neurally based behaviours with which they are associated, that this paper is concerned. Or rather, to put it more modestly, this paper is concerned with one tiny aspect of the visual cortex and its associated neuropsychology By concentrating on this tiny aspect and demonstrating its importance for the history of art, I hope first of all to contribute to the discussion of this volume’s theme. More importantly, though, I hope to encourage others to join in a new type of enquiry, one which will not change art history as it stands, but which will give it new and more robust foundations, establishing it as a humanities discipline founded in science.

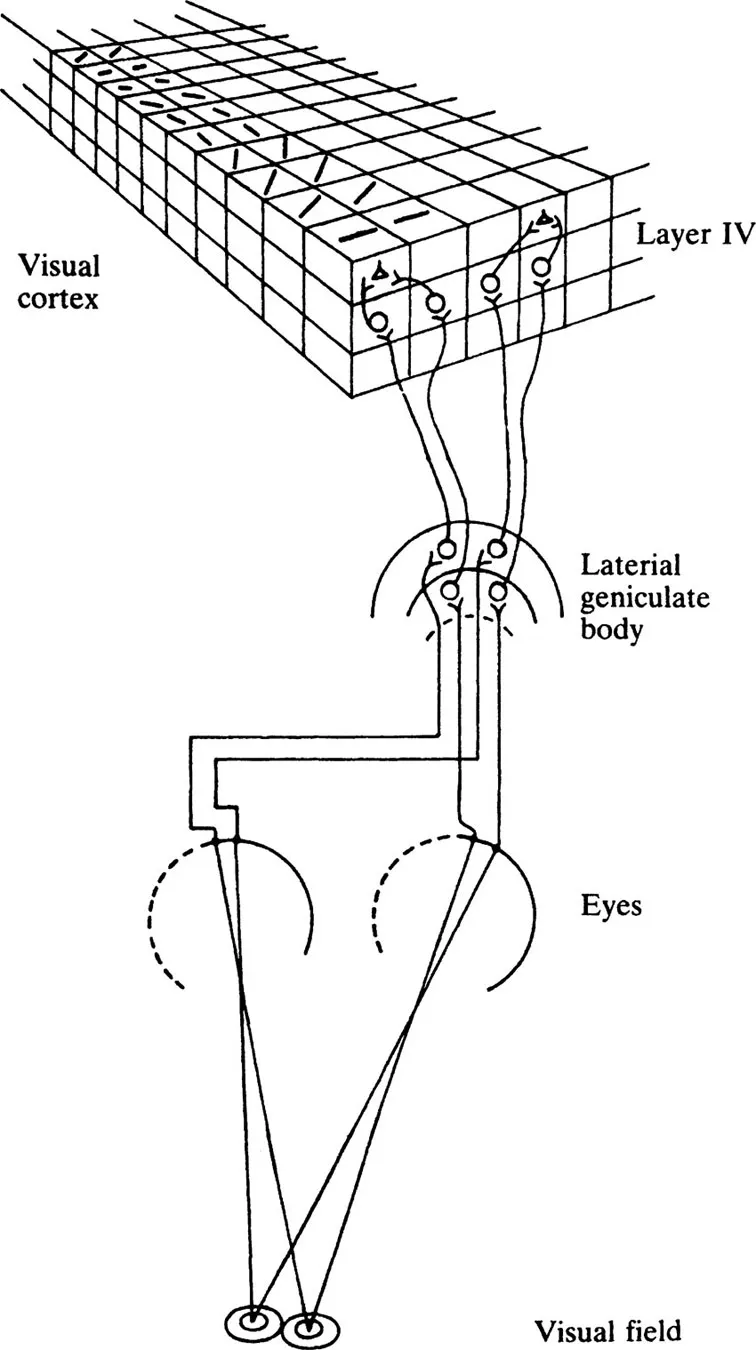

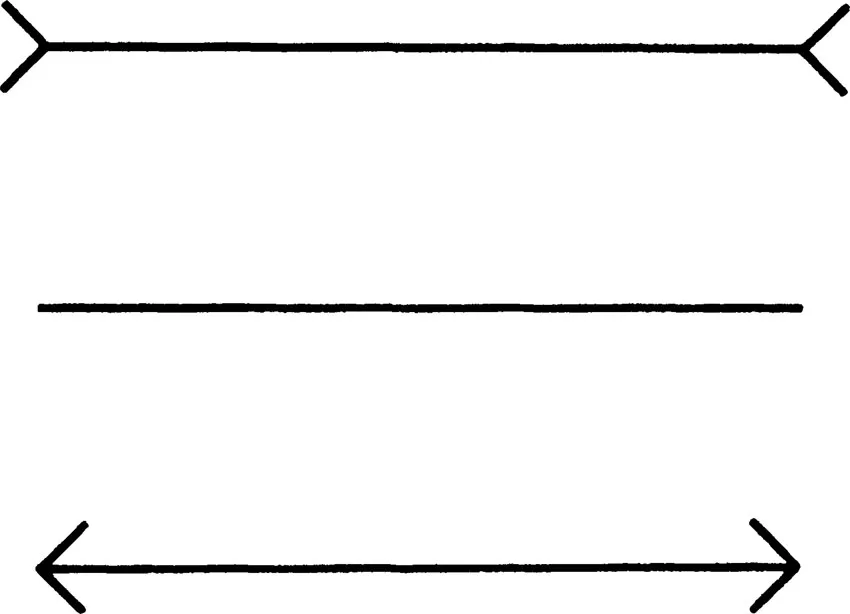

In the present context my concern is with two distinct, but related, features of the physiological structure of the visual cortex and with the behaviours which they support. The two features of our physiology are: (1) that we have neurons whose sole purpose is to respond to a specific phenomenon, such as a vertical, horizontal, or diagonal line (Fig. 1.1), as demonstrated first for cats by Hubel and Wiesel in their paper ‘Receptive fields of cells in striate cortex of very young, visually inexperienced kittens’ 19631 and (2) that such neurons will either become more active and form networks which are better able to perceive that feature, or decline and atrophy if they are not, as demonstrated by Hirsch and Spinelli2, and Blakemore and Mitchell ten years later.3 The behaviours which are supported by these features are: (1) the general tendency of individuals exposed to a particular phenomenon, such as a pattern of horizontal, vertical, or diagonal lines, to develop a preference for looking at it, and (2) the specific tendency of individuals exposed to built environments exploiting cuboid architectural forms to misread two-dimensional arrangements of lines, treating them as if they were three-dimensional, as demonstrated by Dawson, Young, and Choi using experiments with the Müller-Lyer figure (Fig. 1.2).4 Although these conclusions in the fields of neurophysiology and neuropsychology are arrived at by different methods, those in physiology being necessarily based on invasive surgery with animals and those in psychology on the behavioural testing of humans, there is general agreement that they can be responsibly related. Indeed, experiments by Tanaka provide some sort of missing link between them.

Tanaka has shown that in the case of adult monkeys who learn through visual exposure to discriminate different shapes, not only is it possible to locate the neurons in the temporal area which are involved, but it is possible to show that when the taught monkeys are later exposed to the same shapes, a high proportion (39 per cent) of those neurons fire, while in untaught monkeys the percentage is very low (6 per cent).5 Evidently, even in adult primates, the plasticity of the brain is such that repeated exposure to a particular configuration causes particular neural networks to develop, thus facilitating response to it. If there is no exposure no such neural networks will be formed, with the result that the response will be rudimentary. The importance of this work is that it allows us to infer that it is a similar exposure-stimulated development of neural networks able to respond to such configurations as cuboid architectural shapes, or vertical, horizontal or diagonal lines that causes the development of the preferences and susceptibilities to illusion noted in the behaviour-related experiments just referred to. For any art historian to know that exposure to a particular configuration (whether it is manifested in a single object or is a recurrent feature of the environment) stimulates the development of particular neural networks is exciting, since it makes it possible to propose and test for the existence of a causal connection between the formation of particular neural networks as a result of a particular visual exposure and the emergence of a particular artistic trait or style.

1.1 Diagram of area of the visual cortex dealing showing arrays of neurons dealing with lines of varying orientation

1.2 Müller-Lyer figure

For someone wanting to explore the links between painting and architecture, this knowledge is especially important. It suggests, first, that exposure, even as an adult, to an architecture possessing particular features will tend to cause the brain to develop neural networks to deal with them and, second, that since this tendency will equally affect any painter brought up in that environment, his or her work is likely to be to some extent influenced by them. There are few better demonstrations of the predictability of this relationship than the analysis by Dawson, Young, and Choi of responses to the Muller-Lyer test by Australian aborigines, residents of Hong Kong, and residents of the United States. What they argue is that the reason why the aborigine is the least likely to be deceived into thinking that lines of the same length are in fact shorter or longer depending on the angle of the lines adjoining their terminations, is that he or she has had the least experience of carpentered cuboids while the susceptibility to the illusion of inhabitants of the United States is due to the fact that their exposure to such cuboids has been the greatest.6 Exposure to a particular type of architectural environment apparently has a powerful effect on the neural networks governing visual perception and, since these networks are essential for the painter’s work, we would expect painters brought up in different environments to develop different styles naturally.

How might an awareness of such a connection between architectural exposure and pictorial style contribute to a better understanding of the history of painting? We can start by looking at the beginnings of monumental architecture and monumental painting and go on to look at features of their subsequent history The emergence of cut-stone and brick architecture in Egypt and Mesopotamia greatly increased the numbers of true horizontals and verticals in people’s visual field, an increase which was further stimulated by the grids of irrigation ditches, lines of trees, and furrows of grain-producing plants. This increase would have endowed contemporaries with visual cortices much richer in neurons and neural connections responsive to horizontal and vertical lines than those of their predecessors, and individuals so endowed would have experienced a preference for the making of, and viewing of, paintings and reliefs rich in those features. A review of the art of those areas confirms that this is what happened. The art of Egypt and Mesopotamia after about 3000 BC, when the new architecture and landscape types emerge, reveals just such preferences.

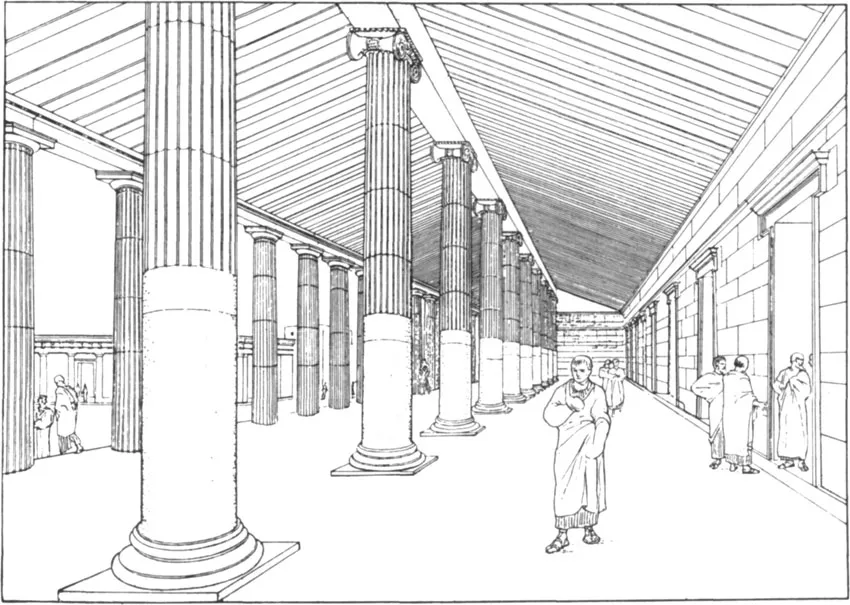

It has of course always been noticed that one feature notably absent from the art of the Ancient Near East is the receding diagonal which is associated with the emergence of linear perspective in Ancient Greece from around 450 BC, and it is now possible to explain why the appearance of this phenomenon must await that moment. It was only the rapid increase in the numbers of receding orthogonals in the Greek visual field, associated with the appearance of stone walls made with prominent horizontal coursing, and the increasing use of coffered ceilings made of either wood or stone between about 550 and 400 BC, that encouraged the preference for the configurations we now characterize as possessing incipient linear perspective. Nowhere would the change in the architectural environment have been clearer than at Athens during Pericles’ building programme and it was indeed in Athens at this time, around 450 BC, that Agatharchus probably formulated the first primitive theory of such a perspective system. It is certainly on Attic vases that we find painters for the first time suggesting depth through the use of receding orthogonals which, if they do not converge on a vanishing point, at least are shown to meet or cross. Nothing like this was found in the painting of Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt where buildings would have presented few such receding orthogonals, principally because walls, whether of stone or brick, were constructed in such a way as to conceal the coursing and because rectangular coffering was a rarity.

The increase in the number of receding orthogonals in people’s visual field that characterizes Classical Greece only accelerated in the Hellenistic period and it is at this time that Euclid formulated the first geometric definition of how we experience such arrays of lines.7 The direct connection between the rise of linear perspective and an increased exposure to interior spaces rich in receding orthogonals is demonstrated by the way writers such as Lucretius, who provide the first verbal accounts of perspective, present it in terms of someone looking down the interior of a stoa or porticus and experiencing a general convergence of lines, ‘as towards the point of a cone’ (Fig. 1.3).8 Individuals who spent much time in such spaces would have had visual cortices more adapted to receding orthogonals than those of any of their predecessors and would have taken pleasure in paintings which showed them. While the formulation of the rules governing linear perspective in Greece was sustained by other aspects of Greek culture, such as the general interest in geometry, the emergence of such a system was above all the biological consequence of the Greek exposure to a new and distinctive architecture.

This dependence of the emergence of a new type of painting on the appearance of a new type of architectural environment prepares us for what happened in the Roman period. From the time of Augustus onwards, coursed masonry was increasingly replaced by concrete, brick, and veneered marble surfaces, all of which were lacking in prominent lines, while rectangular plans and elevations were increasingly replaced by curved ones. Receding orthogonals were thus less and less important in the Roman visual field and, as if in consequence, linear perspective progressively loses its importance in Roman painting.

1.3 Interior of Stoa at Priene, second century BC (after Schade)

When, therefore, applying neuropsychological principles would we expect linear perspective to reappear? The answer is when there was another dramatic increase in the number of receding orthogonals as occurred in Ancient Greece and that points us to one city at one period. Only in Europe did coursed masonry remain an important feature of architecture, only in late mediaeval Italy does it again become common, and only in one urban environment is it associated with rectangular buildings. Venice had many magnificent structures, but as in ancient Rome most were made of brick or covered in marble veneer, while the city’s arteries, like the Grand Canal, were curved. Late mediaeval Rome was little more than a collection of grand churches isolated among piles of rubble and mountainous ruins, separated from each other by a sinuous River Tiber and joined by meandering roads. Siena had many new stone buildings but they were all built along a spiralling road system, while its main Piazza had a concave floor and was surrounded by curved facades. Only in thirteenth and fourteenth century Florence, the fastest growing city of Europe, was there a large resurgence of coursed masonry, first in buildings such as the Bargello and the Palazzo Vecchio and then in hundreds of palaces (Fig. 1.4). Only in Florence, too, was a rectangular urban Roman core adjoining a dead straight river extended by the construction of large rectangular areas of new housing laid out along straight streets (Fig. 1.5). Only in Florence, in other words, was the increase in the number of receding orthogonals so dramatic as to begin to reconfigure the neural networks of its inhabitants with the effect that they could better deal with them.

It is thus in Florence that an understanding of the principles governing neural growth would lead us to expect the emergence of a painting style which exploited receding orthogonals as never before, and it is in someone brought up in that environment that we would expect the clearest recognition and best understanding of the phenomenon to develop. Brunelleschi, born in the city in 1378, was such a person and the connection between his discovery of perspective and his experience of architecture is ill...