This is a test

- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This edited scholarly volume offers a perspective on the history of the genre of the nude in the Middle East and includes contributions written by scholars from several disciplines (art history, history, anthropology). Each chapter provides a distinct perspective on the early days of the fine arts genre of the nude, as its author studies a particular aspect through analysis of artworks and historical documents from the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries. The volume examines a rich body of reproductions of both primary documents and of works of art made by Lebanese, Egyptian, Syrian artists or of anonymous book illustrations from the nineteenth century Ottoman erotic literature.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Art, Awakening, and Modernity in the Middle East by Octavian Esanu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: The ‘Arab Nude’

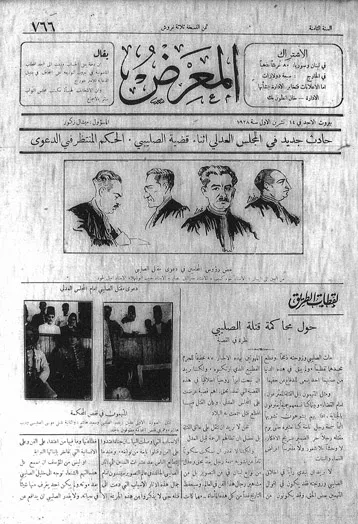

From mid-July to late October of 1928, the Beirut public closely followed local newspapers’ reports on the progress of the so-called “Saleeby case”: the trial of the murderers of the painter Khalil Saleeby and his wife Carrie Aude (Figure 1.1). Khalil Saleeby (1870–1928)—today regarded as one of the forerunners of modern Lebanese art, and one might add, of the Arab world’s fine arts tradition—and his American wife were brutally murdered. The couple was attacked in Beirut by a group of villagers following, according to various sources, a lengthy water-rights dispute in the mountain village of Btalloun, where Saleeby and Aude had their country house.1 Extant newspapers offer very little in the way of details of the murder, though many versions of the story exist, featuring planned ambush, hanging, or even decapitation.2 The earliest report, in al-Ma‘rid’s July 15, 1928, issue, praises the local judiciary and the police for unveiling the secrets of this mysterious case3; by July 20 the paper informed its readers that a man involved in the murder of Khalil and Carrie was prevented from boarding the ship Champollion.4 Several months later, on October 14, al-Ma‘rid published a eulogy to the murdered couple “who could not defend themselves,” and persuaded its readers that Khalil Saleeby was in fact a genius, a man of free thinking, and not a “pitiless monster nor a predator of the honor of women and girls,” as those responsible for the murder had been saying in court.5 Three days later, the newspaper finally announced the court’s conclusions. The judge’s verdict was harsh. All seven villagers faced severe penalties ranging from death and life imprisonment to short prison terms.6 Finally, the October 19 issue announced that the police force in Damascus had arrested and extradited another man involved in the murder of the Beirut painter, and then proceeded to describe in detail the public execution of two of those who had been given death sentences (though in one case, the president of the Republic himself intervened, replacing the death sentence with life imprisonment)—from the appearance of the officials and police escorting the convicts until the moment when the trapdoor of the gallows opened under their feet. The newspaper then encouraged its readers to pray to God to take the offenders’ souls into His infinite mercy but also lent its full support to what it believed to be the principles of modern justice.7

In all these issues of al-Ma‘rid, there are only glancing references to a water dispute, or to any motive at all. There is also that cryptic mention of “the honor of women and girls,” and in later sources one encounters other information, anecdotal observations, stories circulating within the Saleeby family, and more recently, scholarly research and art anthropological field work, bringing in additional insights on the nature of this case, such as what appears to have been a complete lack of understanding and sympathy between the villagers of Btalloun and the solitary artist, or for some Lebanese art historians, a suspicion that ultimately, Saleeby was murdered because he painted nudes.8

Figure 1.1 Page from al-Ma‘rid, no. 766, 14 October 1928.

Archives and Special Collections, Jafet Library, American University of Beirut.

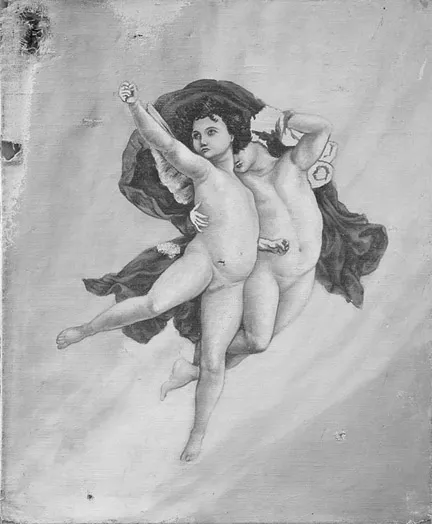

For all the drama of these events, this introduction to a selection of scholarly texts dedicated to the fine arts category of the nude does not intend to suggest that the nude’s presence in the Middle East has always been, or must always be, surrounded by an aura of violence. In fact, the purpose of this book is not merely to prove the opposite but to suggest that our knowledge of the nude in the Middle East continues to be subject to multiple fictionalizations and dramatizations (like the “Saleeby case” above) and that it is time to open the genre to scholarly study. Images depicting nude subjects have been more common than is, or has been, believed in the Western popular or academic imagination. Examples of the latter include respected scholars of the past who saw the nude as a cultural category specific only to Western culture (from Alois Riegl’s assertion that “no nude could possibly be Muslim” to Kenneth Clark’s much quoted statement that “the idea of offering the body for its own sake, as a serious subject of contemplation, simply did not occur to the Chinese or Japanese mind.”)9 A closer study of the nude in the region proves such voices wrong. From religious iconographic representations common in the Christian churches across the Levant— depicting, for instance, asexual nude angels hovering in the skies (Figure 1.2)—to

Figure 1.2 Daoud Corm, No Title, c. 1870s, oil on canvas, 45 × 39 cm.

David and Hiram Corm Collection, Beirut.

Western Orientalist paintings and sculptures imported by the local elites and copied by the first generations of local artists, to even earlier non-Western nude images such as the one at Qusayr ‘Amra bath house, dated to the Umayyad period10—the nude has been, if not as common as in the Western pictorial tradition, far from absent or irrelevant. But I chose the “Saleeby case” to open this introduction in order to set the stage for the particular historical period that most of the contributions to this volume address: the mid- to late nineteenth century, but mainly the first half of the twentieth century, most often called the nahda in scholarly literature, translated (in the view of some, problematically) as the “awakening” but most commonly as the “renaissance.”

This edited volume is the outcome of the exhibition and conference organized in 2015 at the American University of Beirut Art Galleries under the title The Arab Nude: The Artist as Awakener. For the exhibition and conference, which I co-curated with Kirsten Scheid, we proposed to look at the early nudes of the region and the role that this genre of fine arts has played within the context of the early twentieth-century processes of modernization. The title of the Beirut exhibition requires some explanation, for it was chosen in order to deliberately establish a continuity between the spirit of nahda and the cultural and political situation in the Middle East today. We wanted the main title of the exhibition (and the subtitle of the current publication) The Arab Nude to resonate with other controversial and frequently encountered phrases, including the “Arab Spring,” or earlier, “The Arab Awakening.” Certainly, we were aware that the term “Arab” is an anachronistic one—especially when applied to territories that were subject to multiple forms of colonialism, with overlapping and competing identitarian schemes, administrative, ethnic, and confessional politics— but we decided to use it nonetheless, not toward further obfuscating these contradictions and ambiguities but toward highlighting them.11 Phrases like “Arab Spring” and “Arab Awakening” have been used by politicians, scholars, and journalists to discuss, question, predict, or project issues that seem at times to fall squarely within the same limits, contradictions, and binaries that preoccupied nahda intellectuals: tradition and modernity, secularism and religion, national unity and sectarianism, colonialism and national independence, along with a wide range of issues touching upon gender, class, and ethnicity.

One of the main aims of this project was to include the artist, the painter, the sculptor in the list of modern professions involved in this renaissance of letters and culture (as the nahda narrative has often been read). Artists were among the educated professionals, many of them from the upper classes, who joined the encyclopedists and the grammarians, the reformers and the pioneers of national, religious, and secular thought. Most of them traveled to the colonial administrative and cultural capitals of Western Europe in order to learn fine arts techniques, forms, methods, and institutions, which they ultimately perceived as efficient tools for, and their unique contribution to, modernization. Even though their participation was fueled by personal motives and aims, their art was integrated within a particular political discourse dominant at the time among the nahda reformers (liberal, nationalist, socialist, or even Fascist). Nationalistic sentiments predominantly informed many of these artists’ activities, emerging as a progressive and constructive force, in an early instance of what some would later call “subaltern nationalism”; that is, a form of political discourse serving to consolidate a multitude’s resistance to colonial domination.12 This was most visibly manifest in the aesthetic-ethical dimension of nahda, as artists turned art into a tool for the education of the masses, be it art as “religion of the state,” as with Muhammad Naji in Egypt, or as part of a call to launch Western-styled art institutions and humanist art education in order to assert an independent (Maronite-dominated) sovereignty in French Mandate Lebanon, as was the case with Georges D. Corm.13 But in addition to engaging in social and political activities through art, early twentieth-century Arab artists also discovered one particularly efficient painterly tool of “awakening,” the representation of the body without clothes—the Nude. As a figurehead of processes of modernization led by Western-inspired nationalist or liberal elites, the Nude not only denuded and revealed the human body but also evoked openness, authenticity, and liberty—the key values of Eurocentric secular modernity. Thus the “Arab nude” is yet another category that we propose to discuss in the context of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century historical processes, though we are also well aware of the trap set by adding yet another conceptual kit (the “Arab nude”) to the archive of notions that are invoked each time that nahda or “awakening” and “the liberal age” is mentioned (i.e., “Arab thought,” “Arab mind,” “Arab identity,” “Arab subjectivity,” “Arab nation,” “Arab history,” and so forth).14

Several events contributed to the exhibition and to this book. The first was the donation of a large body of Khalil Saleeby paintings to the American University of Beirut, which also included five of Khalil Saleeby’s nudes.15 Another was Kirsten Scheid’s article “Necessary Nudes” (reprinted as Chapter 2 in this volume), which served as a source of inspiration for the exhibition and conference. In her article, Scheid argues that under colonial mandates Arab artists deployed the nude as a “culturing” tool (using the Arabic term tathqif, for disciplining or cultivating), and that the task of the nude was to help recategorize norms for social interaction and self-scrutiny, or even to repudiate the behaviors and desires habitually associated with the Arab “past,” such as male homosexuality, and to cultivate instead a “modern,” “masculine” heterosexual eroticism, buttressed by dutiful feminine compliance.16 This argument is supported by her analyses of nude artworks made in Lebanon under the French Mandate, with particular focus on several genre paintings that provide pictorial commentaries on the reception of the nude in the region, for example Omar Onsi’s 1932 Women at the Exhibition and Moustapha Farroukh’s 1929 Two Prisoners.17 Most importantly perhaps, Scheid’s article encouraged the scholarly community to “unveil” (to use an Orientalist trope common in this context) and de-fictionalize an art historical subject that has often been passed over in silence, prompting many contributors to respond to the idea of the nude as a “culturing” tool by studying aspects of the genre and its historical transformations in Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, Iraq, or nineteenth-century Ottoman Turkey.

Already around the time of Saleeby’s murder, in 1928, the nude was becoming a visible modernizing force, manifest not only in the creation and open display of an increasing number of nude pictures but also in the advent of other culturing forms related to nudity or the unclothed body. Examples are numerous and are examined in greater detail by contributors to this volume: from the launching of new types of periodical publications regularly printing nude imagery and texts (the Lebanese al-Makshuf, al-Nahar and al-Ma‘rid and the Egyptian al-Musawwar) to the publishing of books propagating nudism as a healthy and modern way of living (for example, Sheikh Fouad Hobeiche’s Rasul al-‘Uri [The Messenger of Nudism, 1930], discussed in this volume by Hala Bizri); and from the deployment of the nude in Egypt as a weapon of anticolonialism and a symbolic element of nation building (discussed by Nadia Radwan and Elka M. Correa-Calleja) to its becoming part of a wide range of social, political, and commercial activities (the Muslim Scouts movement, advertising, cinema, erotica). Nudes became, as Scheid has insisted, indexes of modernity, proofs of eligibility for gaining full membership in the mu‘asara (the new era).

To use Kenneth Clark’s now-unavoidable distinction between “nakedness” and “nudity”—the former a state of being without clothes, and the latter a category of representation18—we may say that the development of the genre has been caught in a tense dialectical interplay from its early days onward. While some saw the unclothed body as “naked”—that is, weak and vulnerable, or a source of public embarrassment and disgrace—others saw it as “nude,” that is, as ideal type, mode of knowledge, and efficient tool of modernization. And if we agree for a moment with the Lebanese art historians who have suggested that Saleeby was murdered for painting nudes, then it may have been that the villagers of Btalloun (some of whom were in fact Saleeby’s relatives—the murder ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Transliteration and Translation

- 1 Introduction: The ‘Arab Nude’

- 2 Necessary Nudes: Hadatha and Mu‘asara in the Lives of Modern Lebanese

- 3 Early Representations of Nudity in the Ottoman Press: A Look at Nineteenth-Century Ottoman and Arabic Erotic Literature

- 4 Ideal Nudes and Iconic Bodies in the Works of the Egyptian Pioneers

- 5 The Nudism of Sheikh Fouad Hobeiche

- 6 The Feminine Nude as an Expression of Modernity in the Work of Mahmud Mukhtar

- 7 Bare Language

- 8 Msalkha, or the Anti-Nude

- Works and Sources Cited

- Notes on Contributors

- Index