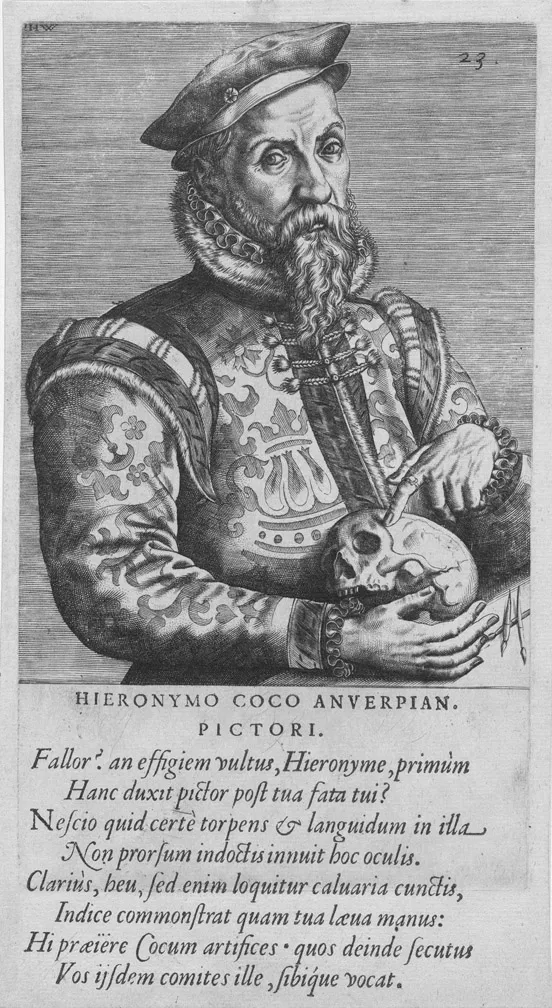

In 1559 and 1561, Hieronymus Cock (1517/18–1570) issued the two sets of prints known today as the Small Landscapes. By this time, Cock was already a well-established print publisher. Son of the painter Jan Wellens de Cock and Clara van Beeringen, Cock was born in Antwerp in 1517 or 1518 (Figure 1.1).1 Having probably trained with his brother Matthys, he entered the Guild of Saint Luke as a painter and master’s son in 1546 and likely took over his brother’s workshop when he died in 1547. Cock also became a member of De Violieren, the chamber of rhetoric to which many artists in Antwerp belonged.2 Though he began his career as a painter, draftsman, and etcher, his publishing and business concerns soon overtook his other artistic aspirations.3 After a possible trip to Italy sometime in the 1540s, Cock married Volcxken Diericx in 1547 and together the couple established their print shop, Aux Quatres Vents, in Antwerp around 1548.4 Cock quickly set out to rival Italian publishers with a number of ambitious large reproductive engravings of classical subjects.5 Within just a few years, he had established one of the most prolific and important publishing enterprises of the Renaissance, emphasizing the production of high-quality artistic prints made by the best printmakers in Europe after designs by leading international artists, past and present.

In order to understand what an extraordinary artistic experiment and commercial risk the Small Landscapes project was, this chapter will investigate the broader contours of Cock’s publications, particularly in the area of landscape. From a fairly early point in his career, Cock began to produce a wide variety of landscape prints, many issued as large sets. Unlike his Italianate and classicizing prints, which are generally both thematically and stylistically consistent, Cock’s landscape prints are heterogeneous, diverse in both content and style. Cock’s willingness to experiment with innovative subject matter and compositional types transformed the nascent field of landscape prints into a robust genre. As Timothy Riggs has put it, “Cock here found a minor genre of print publication and made it into a major one.”6 In this light, the groundbreaking originality of the Small Landscape prints fits within Cock’s broader interest in developing and extending the specifically northern field of landscape prints in conjunction with and counterpoint to his classicizing and Italianate publications.

Drawings into prints

Of the over twenty extant drawings associated with the anonymous Master of the Small Landscapes, Hieronymus Cock employed about half as direct models for the prints.7 It is not clear if Cock commissioned these designs or if he acquired pre-existing drawings from an earlier source or sources.8 The drawings may well have originated in artists’ sketchbooks, which would explain their general consistency in size, almost all of which measure around 13 × 20 cm, the same size as the prints themselves.9 Such sketchbooks were common in artists’ workshops, providing models for use in other finished compositions, especially paintings. Landscapes such as those in the Small Landscape drawings could serve as guides for the backgrounds of painted compositions, lending them both naturalistic detail and compositional variety.10

Two surviving examples of sketchbooks that include these types of landscapes are the so-called Antwerp Sketchbook, now in the Berlin Kupferstichkabinett,11 and the Errera Sketchbook, now in the Brussels Koninklijke Museum voor Schone Kunste.12 Both originated in Antwerp workshops and have been dated between the 1520s and the 1550s.13 Though both sketchbooks include large numbers of imaginary and fantastical scenes in keeping with the world landscape tradition of early sixteenth century, they also contain a select number of drawings of more naturalistic views that appear to have been made from life. The Antwerp Sketchbook includes a large number of drawings representing its namesake city and the surrounding countryside in images that were clearly based on direct observation. Both the Antwerp Sketchbook and the Errera Sketchbook also include a number of purely rural scenes depicting farm-steads, manor houses, and humble cottages in a gentle, rolling terrain. Though even these compositions often resemble the more vast and panoramic views in the world landscape tradition, they approach the local countryside with a directness and an eye for characteristic features that we also find in the Small Landscape drawings. What these examples demonstrate most fundamentally, however, is that drawing the local countryside was an established practice in the early decades of the sixteenth century. The sketchbooks and the Small Landscape drawings, though formally distinct, are nonetheless linked in the scope of their content and the manner of their observations.

If the Small Landscape designs originated within a sketchbook, they would not have conceived as preparatory designs for prints. As such, their transition from drawing to print demanded certain modifications. As was often his practice, Cock edited many of the original drawings to animate the landscapes with small figures. He added small groups of figures, birds, and clouds to several of the extant drawings in a different ink and with a stroke that has little in common with that used in the other elements of the drawings.14 Striking examples of these editorial additions can be seen in several of the preparatory drawings, in which the blacker ink that describes the figures and the birds does not match the rest of the drawing in style or execution (Plate 1). There are a few related drawings, particularly a related pair at Chatsworth, in which the figures were added later in another ink, but by the same artist. However, none of the drawings in this group was used by Cock as a model for the prints. Rather, Cock preferred to employ only those drawings that the original draftsman had left without figural staffage, so that he could edit the unadorned landscapes to his own specifications before printing.

The added figures, with their pointed faces and elegant, if schematic, forms and gestures, closely match the staffage figure types that one sees in Cock’s drawings and other landscape etchings, thus bearing out the notion that they are the result of Cock’s own editorial work.15 Hans Mielke wondered why it was that the original master, who was clearly a gifted figure draftsman, was not the one chosen to rework the drawings. However, if Cock was using pre-existing drawings made as much as a generation earlier, he would not have been able to work with the original draftsman to amend the compositions to his desired specifications. Indeed, Cock regularly sought to control the final effect of the prints and to create a uniformity within the series by making these kinds of editorial interventions himself. In this, Cock recognized and took advantage of one of the basic principles of printmaking, namely that this mutable medium allows for intervention and alteration to an image throughout the many stages of the printmaking process.16

Cock’s decision to publish these drawings as print was a significant one. While this shift from one medium to another might seem inconsequential, it was in fact his most important editorial decision. This type of imagery, previously used solely as preparatory material or as a tool for artists in the studio, was now suddenly widely available outside of artists’ workshops for much wider audiences. As prints, these views gained a new autonomy as independent works of art, opening them up to artistic and aesthetic appreciation on their own merits, to be viewed and collected alongside other prints of more traditional, established artistic subjects.

This move from drawing to print translated peripheral imagery typically used for backgrounds and settings to center stage as a primary subject in its own right.17 This transition calls to mind Victor Stoichita’s structural analysis of metapainting, in which he outlines the complex means by which artists hybridized pictorial genres in the early modern period in ways that upended traditional notions of painting’s primary (sacred) subject and its peripheral or marginal frame. His discussion centers around Pieter Aertsen’s “split painting” of Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (1552), which prominently showcases a still-life tableau in the immediate foreground dominating the pictorial field, while the “main” biblical subject – that is, the scene that traditionally would have been considered worthy of painted representation – is relegated to the lower left corner of the panel, as seen in the background through a doorway into another room. Here Stoichita builds on Hans Belting’s conception of the transition of icons into works of art in the early modern period, whereby aesthetic meanings supplanted the traditional religious functions of images.18 Stoichita sees this transformation taking shape in Aertsen’s painting, writing that “by capturing in its visual field what normally remains outside the frame (the profane, the off-text, the non-painting) and by transforming this off-text into painting, Aertsen marks a significant moment in the history of art.”19 This revolutionary reconfiguration in the relationship between subject and frame, he argues, eventually led to the birth of new pictorial genres, including both still-life and landscape.20 This birth

takes on the characteristic of a “shift” or, perhaps, a “cut.” Born as marginalia, as a reverse, as an accessory (hors d’oeuvre), as an image-frame, in a word as a parergon, still life… becomes an ergon: a work in and of itself.21

The Small Landscapes seem to align with this paradigm, transforming the parergon – the landscape frame traditionally relegated to the distant background as a setting for a more primary, traditionally significant subject in the foreground – into the ergon, the whole of the work. Each view in the series presents an unassuming, humble local landscape as the primary focus of our attention, while the figures who occasionally inhabit them serve strictly as staffage, supporting and underscoring the character of the landscape rather than vice versa. The series simultaneously enacts a second inversion, one of medium, relocating the imagery of quick, private sketches traditionally confined to artist’s studios into the more public, modern medium of print.

It is, however, important to keep in mind that the Small Landscapes were very much an experiment. In his discussion of Aertsen’s 1552 painting, Stoichita stresses that the new primacy of still-life was “in the process of configuration,” still fundamentally tied to and inter...