This is a test

- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Stock Exchange and Investment Analysis

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Originally published in 1973, Stock Exchange and Investment Analysis provides a detailed description of the London Stock Exchange and outlines both the principles and practice of finance, investment, and investment analysis. Split into four sections, the book provides critical analysis of the Stock Exchange and its functions, and the securities available to investors. It also addresses the latest developments in the field of investments and provides a detailed discussion on taxation and portfolio analysis. This book will be of interest to academics working in the field of finance and economics.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Stock Exchange and Investment Analysis by Richard Briston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

PART I: THE STOCK EXCHANGE—HISTORY, FUNCTIONS, CRITICISM

INTRODUCTION

Opinions expressed on the subject of the Stock Exchange tend to be couched in emotional language and to be coloured by the moral and political views of the critic concerned. Two of its more ardent proponents are Harold Wincott, who states:

‘The Stock Exchange is . . . woven into the very texture of our national civilisation and could not be abolished without radically altering our national way of life,’1

and F. E. Armstrong who ecstatically writes:

‘The Stock Exchange as an institution has been evolved by time and perfected by experience. It exists for the purpose of providing a market wherein to buy and sell the world's capitalised values. Here, interests small or large, in the whole of man's activities can be exchanged. It is the Citadel of Capital, the Temple of Values. It is the axle on which the whole financial structure of the Capitalistic System turns. It is the Bazaar of human effort and endeavour, the Mart where man's courage, ingenuity, and labour are marketed.’2

The opposite view was taken by Keynes who severely criticized stock markets in general and the New York Stock Exchange in particular:

‘When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done. The measure of success attained by Wall Street, regarded as an institution of which the proper social purpose is to direct new investment into the most profitable channels in terms of future yield, cannot be claimed as one of the outstanding triumphs of laissez-faire capitalism . . . . That the sins of the London Stock Exchange are less than those of Wall Street may be due, not so much to differences in national character, as to the fact that to the average Englishman Throgmorton Street is, compared with Wall Street to the average American, inaccessible and very expensive. The jobber's “turn”, the high brokerage charges and the heavy transfer tax payable to the Exchequer, which attend dealings on the London Stock Exchange, sufficiently diminish the liquidity of the market (although the practice of fortnightly accounts operates the other way) to rule out a large proportion of the transactions characteristic of Wall Street.’1

1 Beginners, Please (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode for the Investors Chronicle, 2nd Ed. 1960, p. xi).

2 The Book of the Stock Exchange (London: Pitman, 4th Ed. 1949, p. 26).

An altogether more balanced and moderate judgment is that of W. J. Baumol, who, in analyzing the efficiency of the New York Stock Exchange, draws conclusions which could well be applied to that of London:

‘All in all, one cannot escape the impression that, at best, the allocative function (of the stock market) is performed rather imperfectly as measured by the criteria of the welfare economist. The oligopolistic position of those who operate the market, the brokers, the floor traders and the specialists; the random patterns which characterize the behaviour of stock prices; the apparent unresponsiveness of supply to price changes and management's efforts to avoid the market as a source of funds, all raise some questions about the perfection of the regulatory operations of the market. But though its workings are undoubtedly imperfect, it does not follow that they are beyond the pale. Rather, its operation must be judged to be somewhat on a par with that of the bulk of America's business. Far from the competitive ideal, beset by a number of patent shortcomings, it nevertheless performs a creditable job. Bearing in mind that its ramifications were never planned by organized human deliberation, one can only marvel at the quality of its performance.’2

1 The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money (London: Macmillan, 1936, pp. 159–60).

2 The Stock Market and Economic Efficiency (New York: Fordham University Press, 1965, p. 83).

The objects of the next section are to explain the functions of the London Stock Exchange, to describe the mechanism by which it provides a market for investors and a source of capital for the Government and industry, and to assess the extent to which it performs its functions under modern conditions.

CHAPTER 1

The London Stock Exchange—Its History and Functions

In order to appreciate the functions of the London Stock Exchange it is necessary to understand something of its history, for its functions have grown and become gradually more clearly defined over the period of its development. Similarly an understanding of its history involves knowledge of the legal and economic development of the two major groups of securities that are dealt in, namely Government and industrial. For these reasons this chapter is divided into four parts, dealing with the growth of Government securities, the development of the industrial sector, the history of the Stock Exchange, and, finally, its functions.

1. THE GROWTH OF GOVERNMENT SECURITIES

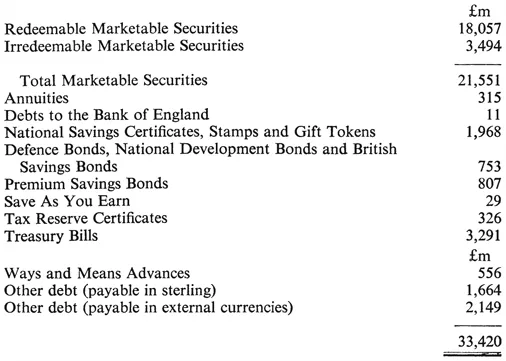

At March 31, 1971, the National Debt of the United Kingdom in nominal terms stood at £33,420 m. composed of the following Government obligations:

Based on Financial Statistics, HMSO May, 1971.

Note: (a) The irredeemable or funded1 securities now comprise only some 10% of the National Debt, whereas up till 1914 they had accounted for between 85% and 99%. Their growing unpopularity has meant that more reliance has been placed by the Government on unfunded debt, the bulk of which is repayable on or before a definite date. The last major issue of irredeemable securities was that of 3½% War Loan in 1932, when £1,920,804,243 of the stock was issued to replace a 5% War Loan stock, which had been effectively redeemable in that it could be tendered in payment of death duties. £1,909·4 m. 3½% War Loan is still outstanding and this particular stock comprises more than half of the total of irredeemable Government securities. For this reason it has borne the brunt of the disillusionment of investors with such securities, which was evidenced by the fall in its price from over £100 in the ‘cheap money’ period after the last war to £36 during 1969. As a result, investors who held War Loan, many of whom were widows and retired persons who felt that it offered them a good degree of security, not only lost much of their capital in money terms but also found that the remainder had depreciated further in real terms due to the impact of inflation.

(b) The figure of Ways and Means advances represents temporary advances made by Government departments to the Exchequer.

(c) The amount of other debt payable in external currencies is comprised mainly of amounts due to the US Government and the Canadian Government under agreements made at the end of the Second World War.

(d) If sundry items such as Ways and Means advances, other debt, and debts to the Bank of England are excluded, the remainder of the Debt is held primarily by investors. These securities may be either irredeemable, redeemable on or before some definite future date, or repayable on demand. In the case of loans which are repayable on demand, such as National Savings Certificates, Defence Bonds, Premium Savings Bonds and Tax Reserve Certificates there is clearly no scope for a market, for they may be bought from or sold to the Government at specified prices on demand. Of the redeemable securities, Treasury Bills are repayable 91 days after the date of issue, so that there is once again little call for an organized market other than is provided by the normal banking mechanism to enable holders to liquidate their Bills. The actual market in which Bills are purchased from the Government at each date of tender is, of course, highly organized. However, in the case of redeemable securities which are not repayable in the very short term and irredeemable securities there is a definite need for a market in which investors can exchange their holdings for cash. Such a market is provided by the London Stock Exchange and at March 31, 1971, the nominal value of Government securities quoted thereon stood at £22,533 m. This differs from the total of marketable securities included in the above analysis of the National Debt due to differences of definition, such as the practice of the Stock Exchange to include in the total quoted nominal amount of a given security, any amounts which have been tendered in payment of death duties and are now held by the National Debt Commissioners. Such amounts arise, for example, in the case of 4% Funding Loan 1960-90 and 4% Victory Bonds and are excluded by the Treasury in their calculation of the total of the National Debt.

1 The word ‘funded’ originally referred to loans whose interest was secured against specific revenue of the State. With the passage of time it came to be applied to loans for which the Government was not required to make any provision for redemption.

The origins of the National Debt are surrounded by a certain amount of confusion, which is the result of problems of definition rather than lack of information. Certainly most authorities trace the National Debt back to the last half of the seventeenth century, though they are not unanimous as to the actual point of origin.

During the seventeenth century one of the most common methods of short-term borrowing by the Crown was by means of tallies, which were wooden sticks with notched sides indicating the amount due from the Exchequer to the holder of the tally. After the Restoration steps were taken to formalize their use. In 1660 their holders were granted interest and repayment was guaranteed against given classes of Exchequer revenue, while an Act of 1663 provided for their repayment in the order in which they were issued and also made them negotiable by endorsement.

The formalization of the use of tallies was accompanied by the introduction of fiduciary orders or notes issued by the Exchequer in payment of debts. Ultimately these orders were sold by the recipients, usually at a heavy discount, to bankers who at the time were mainly goldsmiths or Jews. On December 18, 1671, Charles II ‘stopped’ the Exchequer, defaulting on a total of £1,328,526 of fiduciary notes, most of which were held by the goldsmith bankers. He did, however, agree to pay interest at 6% on the amount due and did so for six years, after which he again defaulted. After many years of dispute a compromise was effected in 1705 whereby the Government assumed responsibility for half of the amount due and issued £664,263 6% notes to the original holders of the debt and their descendants.

Up to the Revolution of 1688 the Crown continued to rely on short-term borrowings for its finance. Thereafter the concept of the State grew in importance and lenders came to be regarded as giving credit to the State rather than to the Crown. Though this did not necessarily represent a very material increase in credit-worthiness it did make the issue of long-term loans much easier. In 1693 the first such loan was offered to the public, who were asked to subscribe £1 m. either by way of participation in a tontine or by the purchase of an annuity. The Tontine Loan, by which the seven survivors out of all the lenders would receive the highest returns, received subscriptions totalling £108,000, the remainder of the £1 m. consisting of purchases of annuities.

In 1694 the first permanent irredeemable State Debt was accepted on the establishment of the Bank of England. This was formed by a syndicate which agreed to lend £1·2 m. to the Government in perpetuity, receiving in return an annual payment of £100,000 (comprising interest at 8% totalling £96,000 and management expenses of £4,000) plus the right to do banking business and to issue currency notes up to an amount of £1·2 m. At the same time the Government raised a further £300,000 through the sale of annuities and later in 1694 issued a State Lottery Loan of £1 m.

In 1696 Exchequer Bills were issued for the first time. These were the offshoots of the tallies and the forerunners of the Treasury Bill. They were mainly of denominations of £5 and £10, carried interest of £4 11s% per annum and were repayable in the short term at a specified date. In the same year a financial crisis occurred, the Bank of England suspended payments and Exchequer Bills and Bank of England notes fell to discounts of 60% and 20% respectively. Three sources of finance were now resorted to. The permanent debt was increased by means of a perpetual loan of £2 m. from the East India Company, in return for which it was given a monopoly of trade with India. The long-term debt was increased by a further issue of State Lottery Loan amounting to £1·4 m. and the short-term debt was augmented by another issue of Exchequer Bills bearing interest at £7 12s% per annum. At the same time the capital of the Bank of England was increased by £1 m., much of which was subscribed for by holders of Exchequer Bills, who were given credit for four-fifths of the amount of their bills to set against the amount due to the Bank by way of subscription to the increased capital. The million pounds thus raised was lent to the Government and the Bank of England was, in return, allowed to increase its note issue by the same amount.

Thus by the end of the crisis the foundations of the National Debt had been well and truly laid and it amounted at the end of 1698 to £17·3 m. The actual date at which the Debt can be said to have begun is stated by different authorities to be either 1671, when the Exchequer was stopped, 1693, when the first State Loans were issued, or 1694, when the Bank of England was formed and the first perpetual Government Debt was established. Of these dates 1694 seems preferable, but the problem entirely depends upon the way in which ‘National Debt’ is defined—whether it should be Crown Debt or Government Debt, and whether it is to be regarded in its inception as perpetual, long-term or short-term debt.

Since 1698 the National Debt has increased from £17·3 m. to over £30,000 m. By far the greatest part of this increase has been due to Government expenditure in times of war. By 1714 at the end of the war against Louis XIV the Debt had more than doubled to £36·2 m. It then rose steadily through the eightee...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Table of Contents

- PART I: THE STOCK EXCHANGE—HISTORY, FUNCTIONS AND CRITICISM

- PART II: STOCK EXCHANGE SECURITIES AND OTHER INVESTMENTS

- PART III: THE ANALYSIS OF INVESTMENTS

- PART IV: TAXATION AND PORTFOLIO ANALYSIS

- APPENDIX

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- TABLES

- INDEX