![]()

Chapter 1

The Making of Victorian Manliness

When Benjamin Spock the child-care guru died in 1997, his son John in a post-obit interview said, ‘He was very Victorian. He’s never been a person who gave me a hug. He wouldn’t kiss me’.1 In describing the cold detachment of his father as ‘Victorian’, he fed into a nexus of assumptions and associations that people commonly hold about Victorian men in general and fathers in particular. He anticipated that we would all know what he meant. Victorian men have been commonly believed to be harsh, stern fathers, subjugating their families by exploiting their legal, financial and often their physical powers over their dependants. They have been viewed as emotional illiterates, domestic despots, bolstering their phallocentric view of the world in the men-only institutions of their professions, bastions of the privilege of their sex. Their era has been seen as the age of the stiff upper lip, when feelings, especially sexual feelings, were kept firmly under wraps. This stiff upper lip, so necessary to survive the daily floggings of the English Public School, has been closely linked with the Age of Empire, when Britain ruled the world; in the face of catastrophe, a Briton could be relied upon to cope with characteristic British phlegm and understatement. ‘Victorian’ has become an adjective of derogation; applied to sex it implies suppression and denial; applied to morals it implies hypocrisy; apply it to religion and we perceive a culture where what is seen is more important than the creeds that underlie it.

What has informed these beliefs? The popularity of deprecating Victorian values, and encouraging their caricature, started soon after Victoria’s death. Lytton Strachey, in Eminent Victorians,2 shifted the hagiography of the heroes and heroines of the era to revelations of their feet of clay. As subsequent generations continued to distance themselves from the era, it became increasingly acceptable to belittle the institutions of the time, and we are only now beginning to recognise this for what it was, as modern enquiry gets the record straighter.

There has been a good deal of focus on Victorian masculinities over the past 40 odd-years, starting with Newsome’s Godliness and Good Learning, in 1961. Newsome constructs his Victorian masculinity by examining the shifting precepts of the education offered in the public schools and he draws heavily on the memoirs of Archbishop Benson and his family. Mangan and Walvin’s collection of essays, published in 1987, similarly posits a masculinity largely assimilated through schooling, while the contributors to Hall’s Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age, in 1994, pursue some of the theological debates through contemporary fiction, particularly Kingsley and Hughes. Vance’s seminal work, The Sinews of the Spirit, of 1985, unites threads of education, philosophy, the new economics and theology.

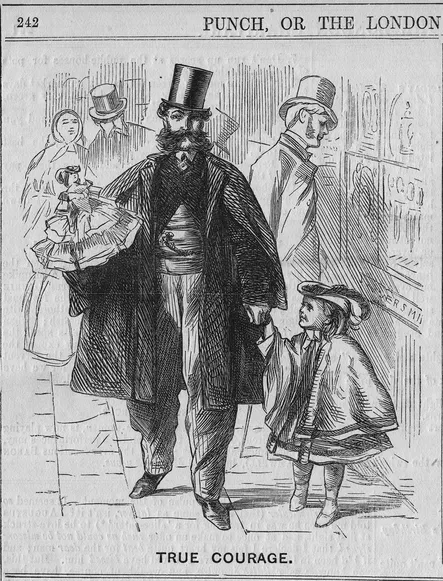

Figure 1.1 Punch Cartoon December 10 1859

Tosh has adopted a significantly different stand and in A Man’s Place: Masculinity and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England, he has reframed many of the earlier commentators’ core material. His thesis proposes that domesticity is central to the Victorian culture of masculinity and that this has been given scant attention in the past because of the skewed positioning of historical commentators. He argues that pre-feminist historical research (that is, before 1970), by confining women to hearth and home, denied them any meaningful role in society. In identifying the domestic as the sphere of women who exercised no power, historians overlooked it as an area which defined so much of a man’s power. Tosh posits that it was in the home, the seat of patriarchy, or ‘father-rule’, that men usually wielded power and drew self-respect from their exercise of it. This masculinity defined by domesticity is beset by contradictions. As Tosh says, the expectation that men spend non-working hours at home assumes a companionate marriage, based on love, common values and shared interests, but this was at variance with a belief in rigid sexual difference and in innate female dependence and inferiority.3

Tosh, in common with other commentators like Newsome, and the contributors to Mangan and Walvin and Hall’s anthologies, draws heavily on the archives of families like the Bensons to furnish his theory. In all he explores seven families in some depth, but the Benson family dominates, perhaps because of the sheer volume of memoirs and diaries left behind by Edward Benson, the schoolmaster who became Archbishop of Canterbury, his wife, three sons and two daughters. A.C. and E.F. Benson, two of the sons, between them wrote ten books about their family affairs.4 Both parents kept meticulous diaries and Edward Benson assuaged his grief when his eldest son Martin died of meningitis, at 17, by writing an account of his son’s life and the growth of his faith. Such a welter of fine detail about the functioning of one family can cloud judgement of more common practice. The Bensons’ devotion to Godliness and good learning is not necessarily an indicator of the established order of the time, in spite of Newsome’s declaration that they give ‘a wonderfully clear picture of Victorian life’5 and Tosh’s assertion that Edward Benson’s exercise of patriarchal power, and the dissimulation of demonstrations of love for his children, was a mid-Victorian norm. Tosh takes care to present both sides of the argument. He assembles an impressive array of empirical evidence of fathers involving themselves closely in the care of their children in infancy. He balances works advocating commitment to active and involved fatherhood, such as William Cobbett’s 1830 Advice to Young Men6 with Carlyle’s outspoken revulsion at his friend David Irving’s close attention to his new baby:

Irving’s talk and thoughts return with a resistless biass [sic] to the same charming topic, start from where they please. Visit him at any time, you find him dry-nursing his offspring; speak to him, he directs your attention to the form of its nose, the manner of its waking and sleeping, and feeding, and digesting.7

This passage, quoted in full by Norma Clarke in her closely argued essay ‘Strenuous Idleness: Thomas Carlyle and the man of letters as Hero’ in Manful Assertions, and abbreviated by Tosh in A Man’s Place, leads him to the view that it was Carlyle’s standpoint that gained ground through Victoria’s reign, not the example of the Prince Consort’s close involvement with the royal nursery. But he does make an important point about the centrality of the hearth in understanding Victorian masculinity. The Industrial Revolution, and the creation of a manufacturing industry, had given rise to a new middle class who earned their living with their heads in counting houses instead of with their hands in the fields, but Tosh points out that in 1851 more of the middle classes still lived over, or adjacent to, their work premises than went beyond the home to work.8 For many children, fathers were an ever-present influence in their daily lives.

As Mark Girouard makes clear in The Return to Camelot, there are several other equally powerful forces which interplay in this complex of masculinities. Girouard focuses on the nineteenth-century slant given to traditions of chivalry and explores how both chivalry and Christian manliness were influenced by rising socialist ideals.9 The Return to Camelot is a compelling account that traces the European chivalric code through its metamorphosis into an Anglo-Saxon behavioural maxim which believed that if a man was behaving badly (such as panicking in the face of death) he was probably an italian, or other foreign Johnny. The italians were a popular target for Trollope’s wit. Miss Altiflora, whose great-grandmother was a Fiasco, and her great-great-grandmother a Desgrazia, in Kept in the Dark,10 is typical. The principle that the ideal knight was brave, loyal, true to his word, courteous, generous and merciful lived on in codes of gentlemanly behaviour, particularly in how gentlemen behaved towards women. The celebration of these ideals found expression in what might be termed a designer style, a growing taste for medieval styles of architecture and decoration, which starts to merge imperceptibly with the Gothic, as the eighteenth century came to a close. Windsor castle was remodelled on medieval lines in the 1830s and Scott’s novels, Ivanhoe especially, spread the taste to a very wide audience. Its apogee was reached with the Eglinton Tournament, the extravaganza of parade and jousting held in 1838, most certainly the inspiration for the Thorne’s fête champêtre in Barchester Towers, and itself inspired by the tournament that opens Scott’s Ivanhoe.11

Girouard stresses the importance of Kenelm Digby’s The Broad Stone of Honour, first published in 1822, in the development of the spread of chivalric ideas, propounding the thesis that a prosperous middle-class man cannot become a gentleman.12 For Digby, this is where England lost her way, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, when men who might have lived as gentlemen turned to commerce. The belief that it was ungentlemanly to betray an interest in money owed much to Digby. The Broad Stone of Honour gave rise to an entire genre of Victorian fiction writing (largely in defiance of his principles) which explored themes around gentlemanliness and whether it came from birth, breeding, or an innate characteristic that transcended factors...