![]()

Chapter 1

China's New Diplomacy Since the Early 1990s: An Introduction

Chinese diplomacy has undergone several major transformations since the early 1990s. Immediately following the Tiananmen Square incident in the spring of 1989 when the pro-democracy student movement was crushed by the Chinese government, major Western powers imposed economic, trade, political and other sanctions on Beijing.

To break out of the diplomatic isolation. China attempted to improve and strengthen relations with its Asian neighbors first. Vice Premier and Foreign Minister Qian Qichen, nicknamed the "godfather of contemporary Chinese diplomacy", masterminded these efforts. This "good neighbor diplomacy" (mulin waijiao) worked successfully. As a result, relations between China and the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) greatly improved. This was significant given the fact that many of these nations remained firmly anticommunist not long ago. Even disputes over the controversial Spratly Islands were temporarily shelved, making way for closer economic and political cooperation. China-Japan relations were also strengthened. In 1990 Japan became the first great power to lift economic sanctions against China and resume economic and political dialogues with Beijing. In October 1992 China welcomed Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko to Beijing, signaling restoration and expansion of Sino-Japanese relations. The Republic of Korea (ROK or South Korea), partially due to its own nordpolitik policy, normalized and established diplomatic relations with the Beijing government in 1992 and severed formal ties with Taiwan which it had maintained since the Chinese civil war separated Taiwan and mainland China in 1949.

By the mid-1990s, as Chinese economic power continued to grow and as China became more self-confident, talks of "revitalizing the Chinese nation" (zhenxing zhonghua) became prevalent inside China. Increasingly the Chinese government and the Chinese public began to consider China as one of the great powers in the world. Built upon its successful "good neighbor diplomacy", China refocused on big powers in its foreign relations. Chinese leaders started to travel to major capitals and invited their foreign counterparts to visit Beijing. Most notably, this "great power diplomacy" (daguo waijiao) resulted in President Jiang Zemin and PresidentBill Clinton's exchange ofvisits in 1997 and 1998. As a symbol of China's growing importance in the global economy, China was eventually admitted into the World Trade Organization (WTO) at the beginning of the new century, after some 13 years of tough negotiations with the United States.1

China desires a world order that is peaceful and conducive to continued economic growth and stability at home. It seeks international cooperation to achieve policy objectives. By mid-2009, China's foreign exchange reserve had reached over $2 trillion, much larger than that of any other country. This, together with the fact that China fared better than most other major economies in the global economic downturn of 2008-2009, makes it possible for China to expand trade and investment and enhance its political influence in every corner of the world.

In the first three decades of the People's Republic of China (PRC)'s history (1949-1979), energy concerns were only a minor factor in Beijing's national security and strategic assessment. China's own oil fields, such as Daqing in the Northeast that was first discovered in 1959, had produced enough oil to keep China self-reliant. Since the end of the 1970s when China re-opened its door to the Western world and adopted economic reform policies, the Chinese economy has been expanding at an average of 10 percent annual growth rate. This rapid expansion requires enormous resources, especially energy and raw materials. Since the mid-1990s China has been seeking oil and other energy and natural resources in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, Central Asia, the South Pacific, Southeast Asia and elsewhere. This new "energy diplomacy" (nengyuan waijiuo) has become a key component of Chinese foreign policy in the new century since energy security has become essential for China to achieve its strategic goal of quadrupling its gross domestic product (GDP) from 2000 to 2020.

At the beginning of the 2000s nearly two-thirds of China's energy still came from coal, and over four fifths of its electricity was created by burning coal. In 2007, China mined 2.5 billion metric tons of coal, equivalent to 46 percent of total world production—more than the United States, the EU, and Japan combined.2 More than 40 percent of China's rail capacity was devoted to transporting coal across the country. In 2007 China became a net importer of coal. It can still meet about 90 percent of its overall energy demand with domestic supply. This is projected to be near 80 percent in 2020.3 China will strive to meet its energy needs mainly through domestic supply. On the other hand, it will take an active part in eneigy cooperation with other countries.

Until the early 1990s, China was still an oil exporter. That changed permanently in 1993 when it became a net oil importer. Though the global economic crisis slowed down China's demand for eneigy, the Chinese economy, helped by government stimulus packages to expand domestic consumption, had shown signs of recovery by early 2009, and energy needs are expected to grow in the years ahead. Oil now accounts for just about 19 percent of China's energy needs, but China's oil demand is predicted to more than double by 2030 to over 16 million barrels a day, according to the International Energy Agency, as more Chinese rise from poverty, move out of villages and buy cars. The number of vehicles in China rose sevenfold between 1990 and 2006, to 37 million. In 2009 China surpassed the US to become the world's biggest automobile market, selling a total of 13.6 million vehicles, compared with 10.4 million sold in the US. The streets of major Chinese cities are crammed with cars driven by the new middle class. Gasoline shortages in 2007 and 2008 created long lines at gas stations across China. China is adding cars at such a rate that by 2030 it could have as many as 300 million vehicles.4 If that happens, by then China and the world will be in a dire situation unless renewable energies are developed.

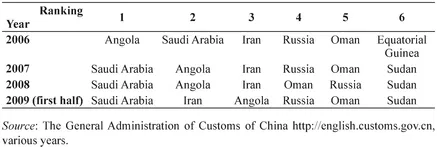

In the several years after it became a net oil importer in 1993, China's oil imports were increasing by 10 million tons yearly. By 2003, the amiual increase reached 20 million tons. In 2007 China's total oil imports reached 197 million tons, with 45 percent of the crude oil coming from the Middle East, 32.5 percent from Africa, and 3.5 percent from the Asia and Pacific region.5 (See Table 1.1). Given that major oil exporters in these regions such as Iran, Sudan, Nigeria, and Libya are politically unstable, China has to diversify the sources of its oil imports, with increased attention to Central Asia, Russia, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific. Top Chinese oil companies—China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), and China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (Sinopec)—have been very active in acquiring exploration rights from Mauritania and Angola to Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, and Chinese oil workers are becoming a growing presence in the Middle East, Africa, Central Asia, and Latin America.

Table 1.1 Top Oil Exporters to China: 2006-2009

To deal with the worsening energy issues and ensure the sustainable and steady development of the national economy, China's inter-ministerial National Energy Administration (NEA) began operation in July 2008. According to Xinhua, China's official news agency, the new institution consists of nine departments, with 112 personnel. Its main responsibilities include drafting energy development strategies, proposing reform advice, implementing management of energy sectors, putting forward policies of exploring new energy and carrying out international cooperation, among others.6 In 2005 China also began work on a strategic oil reserve in coastal Zhejiang province that would allow the country to operate without imports for as long as three months.7

Seeking and preserving energy is not the only objective of China's new diplomacy. China has multi-layered interests and manifold purposes in each of the regions where it has conducted active diplomacy. It is looking for new markets for its consumer products. Chinese firms are beginning to invest in overseas markets and purchase foreign assets. For example, Chinese companies have been purchasing and investing in Africa since the turn of the century. Between 2005 and 2006, Chinese investment in Africa jumped from $6.2 billion to $12 billion.8 In October 2007 China's largest bank, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC). purchased a 20 percent stake in Standard Bank, South Africa's largest bank by assets and earnings, for $5.5 billion, representing the largest foreign direct investment (FDI) in South Africa by then.

In addition, the Chinese government has been projecting a new national image as a responsible, friendly and peaceful player in international affairs. By September 2009, China Central Television (CCTV) had set up six channels to broadcast news globally in English, French, Spanish, Arabic, Russian and Chinese around the clock to counter the perceived distorted coverage of China by foreign media. It is conducting new economic and cultural diplomacy beyond its traditional focus on Asia, North America and Western Europe. Like other states, China uses its growing soft power to win foreign friends and gain international influence.

China is learning to promote and exercise its soft power by establishing Confucius Institutes around the globe.9 The Confucius Institute is a non-profit public institution which aims at promoting Chinese language and culture and supporting Chinese teaching internationally. Normally a Chinese institution of higher learning will partner with a counterpart abroad to jointly operate the Confucius Institute locally. The headquarters in Beijing, the Office of Chinese Language Council International or Hanban, offers financial and teaching support to these institutions abroad. Chinese language instructors have been dispatched and books have been sent to many of these Institutes. By December 2009, over 400 Confucius Institutes had been established in 87 countries.10 China's Ministry of Education estimates that by 2010, there will be approximately 100 million non-Chinese worldwide learning Chinese as a foreign language, and 500 Confucius Institutes will have been set up worldwide. Hanban aims to establish 1,000 Confucius Institutes by 2020.11 Meanwhile, foreign students are flocking to China to study. By the end of 2007, the total number of foreign students in China reached 200,000.

Very significantly, the new diplomacy is no longer monopolized by the Chinese government; the public is increasingly involved in the process. Public diplomacy (gongzhong waijiao), whose tools include cultural and educational exchanges, business links, tourism, sports, and other people-to-people contacts, has greatly expanded between China and other countries. As a supplement to formal state-to-state diplomacy, public diplomacy has been instrumental in China's efforts to create and present a friendly image abroad. Sending medical teams (yiliaodui) to work abroad lias traditionally been part of China's public diplomacy. China sent its first medical aid team to Algeria in 1963. As of the end of 2008, China had sent more than 20,000 medical workers abroad, helping 260 million patients in 69 countries and regions across the world.12

The good neighbor diplomacy, great power diplomacy, energy diplomacy, and public diplomacy are all means to achieve the PRC's major foreign policy objectives, intended to help develop China into a major economic, political, cultural and military power by the mid-21st century. In an attempt to better understand China's new diplomacy, this book will focus on three fundamental questions:

- Why has China practiced new diplomacy since the early 1990s?

- How has China implemented its new diplomacy?

- What are the implications for international political economy?

The first question deals with various motivations behind China's new diplomacy; the second one looks at specific Chinese strategies in achieving its diplomatic objectives; and the third one addresses the impact of Chinese new diplomacy on international politics and economics.

The overarching theme of the book is that China's new diplomacy has been chiefly motivated by the need to secure energy and commodity resources, to search for new markets for Chinese exports and investment, to isolate Taiwan internationally, and to project China's image as a responsible and peaceful power. To achieve these multiple purposes. China has employed a variety of strategies such as summit diplomacy, no political strings attached in trade and aid (except its insistence on the "one-China" policy), avoiding confrontation with existing powers, and active participation by the Chinese public. The author argues that while some of China's practices such as those in Sudan remain controversial, overall China's new diplomacy has been successful. The increasingly sophisticated Chinese diplomacy lias been benevolent, presenting more opportunities than threat to developing countries and to the Western countries that were traditionally—and remain—the dominant outside powers of the developing world. China's new diplomacy also raises issues such as sustainable development and growth model in international political economy.

Main Features of China's New Diplomacy

To achieve its foreign policy objectives, China has adjusted its diplomatic, political, and economic strategies. At the beginning of China's reform era which started in 1978, the prevailing strategy was "bringing in" or yin jin lai (引进来). China enthusiastically attracted FDI, especially from overseas Chinese who remained emotionally attached to their ancestral homeland. It established four Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in 1979 in southern China near Hong Kong, Taiwan and Southeast Asia where the majority of the Chinese diasporas live. The Chinese diasporas have provided the largest chunk of external investment into the Chinese mainland from the very beginning of China's reform era. Eventually China opened up the whole coastal region to foreign investment and trade.

Since the late 1990s, particularly after China became a member of the WTO in 2001, China lias been more deeply integrated into the international political economy. A new strategy in the 21st centuiy is "going out" or zou chu qu (走出 去). China has been actively seeking oil and other energy deals around the world: Chinese companies have started to invest overseas, including purchasing foreign assets. Backed up by a huge foreign exchange reserve. China has been confidently reaching out to every corner of the globe. According to well-known China scholar Harry Harding, China, much like what Japan did in the 1980s, is now in a position to make major investments and purchases in the United States, not just developing nations. Those investments include strategic and iconic ones, such as oil and automobiles respectively.13

From Passive to Active Diplomacy

With growing political and economic strength, China has become more actively involved in international political economy. As Wu Jianmin, a senior diplomat an...