![]()

Introduction

The Art of the Unvarnished Tale

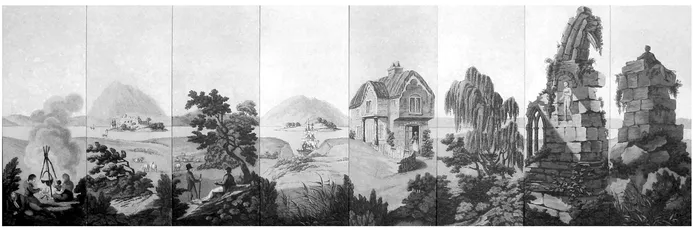

A history of popular games and toys of the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries describes a toy that consists of a number of painted panels, depicting, for example, a pastoral scene in which various figures traverse the countryside, as in “Polyorama or 20, 922, 789, 888, 000 Vues Pittoresques” (c. 1824). What is fascinating about these panels is that they may be arranged and rearranged, forming a different narrative each time. In one rendition a ruin may be next to a village at the center of a landscape, while in another it may be in a sheep-filled pasture toward the very edge of the pictorial frame (Figure 1.1).1 This clever toy clearly represents a combination of genres as well as an exercise in revisionist narrative—any event may be privileged as the centerpiece of the story just as easily as it may hold a place on the periphery. The reading of each self-contained panel is altered depending upon its context. In this game, the emplotment of events, the construction of any history, has a refreshing openness and flexibility which makes the author and the reader self-consciously aware of the order which has been imposed on the events. One can imagine the panel game (and other such amusements as the toy theatre) being used to reflect the players’ varying stances towards the events occurring in their own world. That is, the pastoral scene might serve as an escape from revolutionary turmoil, whereas the toy theatre’s Bastille scene might allow one to engage and perhaps to control that turmoil. In addition to the openness and flexibility here, we may perceive a historical reality producing and being produced—desire and anxiety at work.

The Art of Political Fiction in Hamilton, Edgeworth, and Owenson is a book about the artistic craft and political engagement of three major women novelists of the Romantic period writing in Britain and Ireland—Elizabeth Hamilton, Maria Edgeworth, and Sydney Owenson (Lady Morgan).2 As in the panel game described above, these writers often present their readers with disruptions in their narrative segments, called glosses, that call attention to themselves and momentarily alter the narrative. The forms these glosses usually take are the prefaces and notes of the putative editors, but they also include references to other media, primarily painting and drama, all of which provide an implicit means of expanding the significance of their narratives through non-narrative means. Although glossing is but one of

Fig. 1.1 Facsimile of "Polyorama or 20, 922, 789, 888, 000 Vues Pittoresques."

many literary techniques used to convey political values and beliefs, its subtlety and indirectness made it a preferred and powerful means for women writers of the Romantic period to participate in so-called masculine discussions outside the sanctioned feminine sphere.

The Anglo-Irish Edgeworth and Owenson and the Scottish Hamilton were all prolific writers, producing texts ranging from children’s literature to travel books to moral treatises. They were also quite politically aware. My focus is upon the ways their novels actively critique late-eighteenth-and early-nineteenth-century politics and society, especially through their self-conscious use of glosses. This study features Hamilton’s Translation of the Letters of a Hindoo Rajah and The Cottagers of Glenburnie, Edgeworth’s Castle Rackrent and Belinda, and Owenson’s The Wild Irish Girl and The O’Briens and the O’Flahertys. These novels effectively represent a wide range of types within the Romantic novel: the Oriental tale, the satire, the dialect tale, the novel of manners, the didactic novel, the historical novel, and the national tale, but as this study will show, all employ glosses not only to comment upon their narratives but also to intentionally disrupt them, revealing both their process of structuring and the cultural and social world beyond the texts being structured. The astute reader, in other words, discovers meanings beyond the world of the narrative, which challenge English, Scottish, and Irish institutions and sensibilities.3

To put this thesis in visual terms, the glosses examined here function much like the reflection of the King and Queen in the mirror in Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656). As you may recall, the figures of the royal parents are not visible as sitters in the foreground of the painting; thus the small constructed reflection of them in the background breaks the conceptual frame of the picture, drawing attention to the reality of monarchy, patronage, and parenthood beyond the world of the painting. Velázquez’s inclusion of himself in the painting also forces the viewer to be conscious of the creative process. The back of the immense canvas on the left occupies less than a sixth of the width of the painting but almost the entire vertical expanse of the left-hand side. As we read the painting, our eyes first meet the unseen canvas, making it impossible to view the scene without attention to the process, and the promised product, of Velázquez’s orchestrations. Much of the political art of the writers examined in this study likewise functions to make us conscious of the novel as literary production. As we look into the fictional worlds of Hamilton, Edgeworth, and Owenson, their glosses also force our gaze outward, revealing a world not explicitly represented in the novel but there beyond its frame.

As Mikhail Bakhtin has theorized, the novel’s incorporation of alternative genres reveals a reality outside the text. With “novelization,” other genres “become more free and flexible, their language renews itself by incorporating extraliterary heteroglossia and the ‘novelistic’ layers of literary language, they become dialogized, permeated with laughter, irony, humor, elements of self-parody, and finally—this is the most important thing—the novel inserts into these other genres an indeterminacy, a certain semantic open-endedness, a living contact with unfinished, still-evolving contemporary reality (the open-ended present).”4 Just as the reflection and the presence of the painter and canvas in Las Meninas make evident the presence of a “still-evolving contemporary reality,” the glosses of a novel, when the central narrative shifts to alternative genres, make “contact” with the “contemporary reality” of the author’s life. The tension of these shifts imparts the “extraliterary heteroglossia” of the novel.

This study attends to peripheries (in terms of both the texts and contexts) and argues for an enfolding of the authors, writings, and events of the margins into the central narratives of Romanticism. Hamilton, Owenson, and Edgeworth occupied the liminal position of women writing from the English satellites of Ireland and Scotland; however, all three women were among the most popular novelists at the beginning of the eighteenth century, indicating that both their craft and the issues that most concerned them had stirred the public imagination.5 Their use of both textual and cultural glosses shows a sophisticated understanding of contemporary international political events and cultural trends, an understanding that has faded from view due to changes in reading habits. As H.J. Jackson has argued in his recent compelling study, Romantic Readers: The Evidence of Marginalia (2005), Romantic readers were cued to attend to the periphery, to understand works as fluid and evolving: “[m]any readers had been deliberately trained to mark and annotate books using techniques” that suggest the readers’ consciousness that “books do not grow, but are made; that they are constructed from separate parts that can be dismantled and used again somewhere else.”6 A reviewer of Owenson’s Patriotic Sketches (1807) in Le Beau Monde evidences the marked attention to the construction of the text, that is, to the physical form of the text upon the page and the text as a commercial production: “The appearance of the two volumes, eking out matter which might easily compress itself in one, the fine wire-wove paper exhibiting its neat ‘rivulet of text, flowing through a meadow of margin,’ seemed to us to indicate rather a more substantial reason; and at the end of every ‘Sketch,’ really it required all our politeness to forget the idea of book-making altogether! Miss Owenson will, no doubt, consider this remark rather beneath the dignity of criticism, but truly nine shillings for the two volumes of Patriotic Sketches is a forcible consideration, which the critic feels too sensibly to forget.”7

Owenson’s critic highlights the attention to the text on the page that Gérard Genette believes is inescapable:

No reader can be completely indifferent to a poem’s arrangement on the page—to the fact, for example, that it is presented in isolation on the otherwise blank page, surrounded by what Eluard called its ‘marges de silence,’ or that it must share the blank page with one or two other poems or, indeed, with notes at the bottom of the page. Nor can a reader be indifferent to the fact that, in general, notes are arranged at the bottom of the page, in the margin, at the end of the chapter, or at the end of the volume; or indifferent to the presence or absence of running heads and to their connection with the text below them; and so on.8

This study explores the constructedness of the Romantic novel and its indebtedness to glosses and paratexts, including titles, epigraphs, footnotes, and intertitles, that is, those words that occupy the spaces beyond the central narrative. While most of these terms will be familiar, a brief explanation of Genette’s term “intertitle” may be particularly useful in attending to the discussion of the glosses in Chapters 3 and 5. The intertitle is any title internal to the text, such as a chapter title. As Genette remarks, “in contrast to general titles, which are addressed to the public as a whole and may have currency well beyond the circle of readers, internal titles are accessible to hardly anyone except readers . . . and a good many internal titles make sense only to an addressee who is already involved in reading the text, for these internal titles presume a familiarity with everything that has preceded.”9 Another difference between intertitles and general titles is that they are “by no means absolutely required,”10 thus the author’s decision to employ them may have ironic or comic implications for the narrative.

Examinations of earlier forms of glossing make clear that the gloss and the central text often exist incompatibly. In his study of annotations and marginal art in medieval texts, Michael Camille explores the move from interlinear glosses, “[s]queezed between the lines of text” that “‘spoke’ the same words, only in a different language” to the marginal gloss that “interacts with and reinterprets a text that has come to be seen as fixed and finalized.”11 Camille characterizes thirteenth-century glossing as the “irreverent explosion of marginal mayhem” in religious texts and theorizes the “edge” as both a “dangerous” and a “powerful” place: “In folklore, betwixt and between are important zones of transformation. The edge of the water was where wisdom revealed itself; spirits were banished to the spaceless places ‘between the froth and the water’ or ‘betwixt the bark and the tree.’”12 Hamilton, Edgeworth and Owenson seem to comfortably command the “spaceless places” of the textual margin, understanding the power of glosses that compete with and transform the central narrative.

In the history of the book, as marginalia moved from visual to textual, the uneasy relationship between the center and the edge persisted in the modern age. Anthony Grafton notes that “[e]ven if the intentions of text and annotation have become somewhat blurred, however, the radical nature of the shift from providing a continuous narrative to producing a text that one has annotated oneself seems clear. Once the historian writes with footnotes, historical narrative tells a distinctly modern, double story.” Footnotes used in fictional writing, of course, also engender this “double story.” Though the gloss appears to afford stability to the central narrative, Grafton observes: “To the inexpert, footnotes look like deep root systems, solid and fixed; to the connoisseur, however, they reveal themselves as anthills, swarming with constructive and combative activity.”13 Chuck Zerby, in his study of the footnote, suggests that early “Bibles were battlefields; their left and right margins were the trenches from which scr...